Under a cerulean sky, Dr. Chris Marshall bumps along the beach near Galveston Bay, Texas, in a utility terrain vehicle. The warm Gulf wind ripples his shirt as his eyes stay trained on the sand. It is sea turtle nesting season and Dr. Marshall is in pursuit of his third nest this week — responding to a sighting of tracks on the beach that has come in from one of the 300 volunteers in the Sea Aggies Sea Turtle Patrol that he runs.

A mature Kemp’s ridley, the most endangered sea turtle species in the world, glides through the water near Galveston, Texas. Provided photo

These volunteers have been kindled by his passion for protecting the smallest and most endangered sea turtle in the world: the Kemp’s ridley. Volunteers patrol an 87-mile stretch of beach along the upper Texas coast near the Texas A&M Galveston (TAMUG) campus, where Marshall is a research professor and created The Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research.

When he arrives at the nest, Marshall finds a bonus: the female is still laying eggs. Though Kemp’s ridleys nest during the day — contrary to other sea turtle species — this is still a rare treat and an excellent research opportunity.

A mature Kemp’s ridley turtle taking care of her nest in solitude. Provided photo

Once the turtle has finished laying her 100-125 eggs, covering the nest with sand and has begun her journey back to the sea, Marshall and his team are able to capture her, take measurements and check for tags before releasing her once again.

This female is new to them, though in the past they have encountered turtles with tags from up to 10 years ago that have returned to the beach to lay eggs.

Volunteers collect valuable data from a satellite tag, tracking the turtle's nesting patterns. Provided photo

Attention is now turned to the clutch, the turtle nest. “Because we’re dealing with Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, which are the most critically endangered sea turtles in the world, we actually excavate the nests — we pack them up and send them to an incubation facility at Padre Island National Seashore,” Marshall said in a recent interview with Kinute.

Scientific data has shown that excavated nests have a higher hatching rate than those left on the beach, and these conservation efforts are paramount in bolstering the Kemp’s ridley population. Marshall has found that many experimental decoy nests he and his team have placed have been eradicated due to very high tides and tropical storms.

A look into a Kemp’s ridley turtle nest, with buried egg slightly visible. Provided photo

Additionally, controlled incubation temperatures can manage sex ratio if it is determined necessary to help turtle populations. “One of the cool things about sea turtle biology is that nest temperature determines the sex … we have a fun phrase, we say, ‘hot chicks and cool dudes,’” Marshall said. With global temperatures rising, more female hatchlings are expected to be seen. Ongoing studies along the upper Texas coast are currently underway to ascertain if these measures are necessary in the region.

A sea turtle heads home after its data is collected. Provided photo

A legacy of conservation

Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS) has long been a periodic nesting site for Kemp’s ridley sea turtles and is now their primary nesting area within the U.S. Its protected status makes it an ideal location for colony reestablishment, as it encompasses the longest stretch of undeveloped barrier island beach in the U.S. and is at the northern end of the Kemp’s ridley historic nesting zone. Its emergence as a secondary nesting colony has been an ongoing, concerted effort since the 1970s — one that’s been championed bi-nationally and from multiple agencies as a hedge against extinction.

At the program’s outset, it was theorized that sea turtles imprinted on their natal beaches and that female hatchlings would return to their birth site to lay eggs of their own. Researchers believe sea turtles are guided by the Earth’s magnetic field as a source of navigational information during their incredible migrations.

A baby Kemp’s ridley turtle makes its way to sea for the first time. Fun fact: they are the smallest of all sea turtle species. Provided photo

Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are endemic to the Gulf of Mexico. Rancho Nuevo in Tamaulipas, Mexico, is the primary Kemp’s ridley natal beach — home to 95% of their nests.

Decades of combined conservation efforts saw a substantial increase in the Kemp’s ridley population, however nesting decreased in 2010 and has fluctuated at reduced levels ever since. Scientists are still seeking to determine the cause of this unexpected decline, which demonstrates the importance of continued monitoring and conservation efforts.

Flipper tag from a Kemp’s ridley turtle that has been captured twice by The Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research in recent years. Provided photo

The critically endangered status of the Kemp’s ridley is yet another alarm bell sounding in affirmation of the climate crisis. One that has been tolling in the names of direct harvest, fishery bycatch, coastal development and habitat degradation, marine trash and historic storm events. Through these challenges Marshall’s passion and purpose has been fortified.

From sea to shining sea

At TAMUG, Marshall’s research began at the NOAA Galveston Sea Turtle Facility. NOAA hoped to understand why loggerhead sea turtles were disproportionately being hooked in fishing longlines.

“Most sea turtles have an interesting life history in that, when they hatch from eggs, they swim off shore, get caught up in the currents and then spend a couple of decades in the case of loggerheads — maturing in that oceanic phase … Then they recruit back to the coast … and become coastal. It’s during that phase that they tend to get caught up as bycatch in the longlines fishery and often die,” Marshall said.

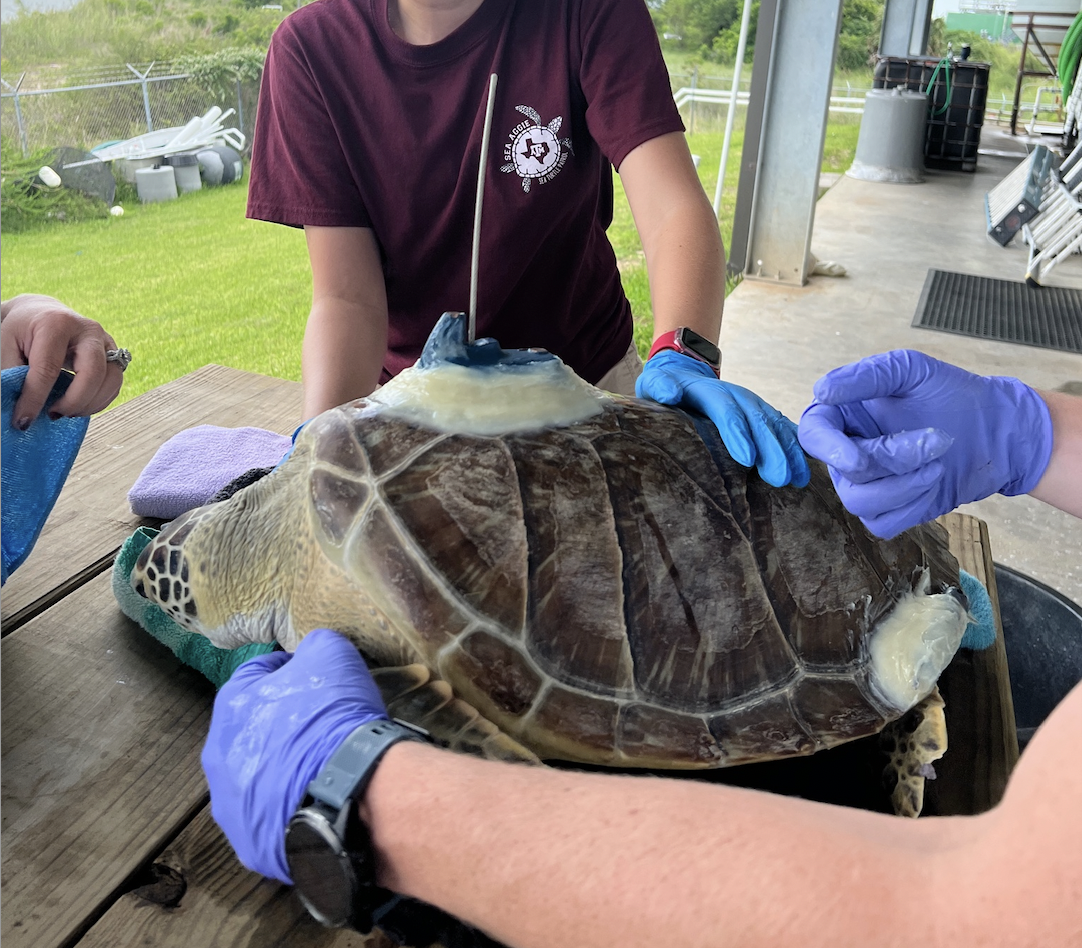

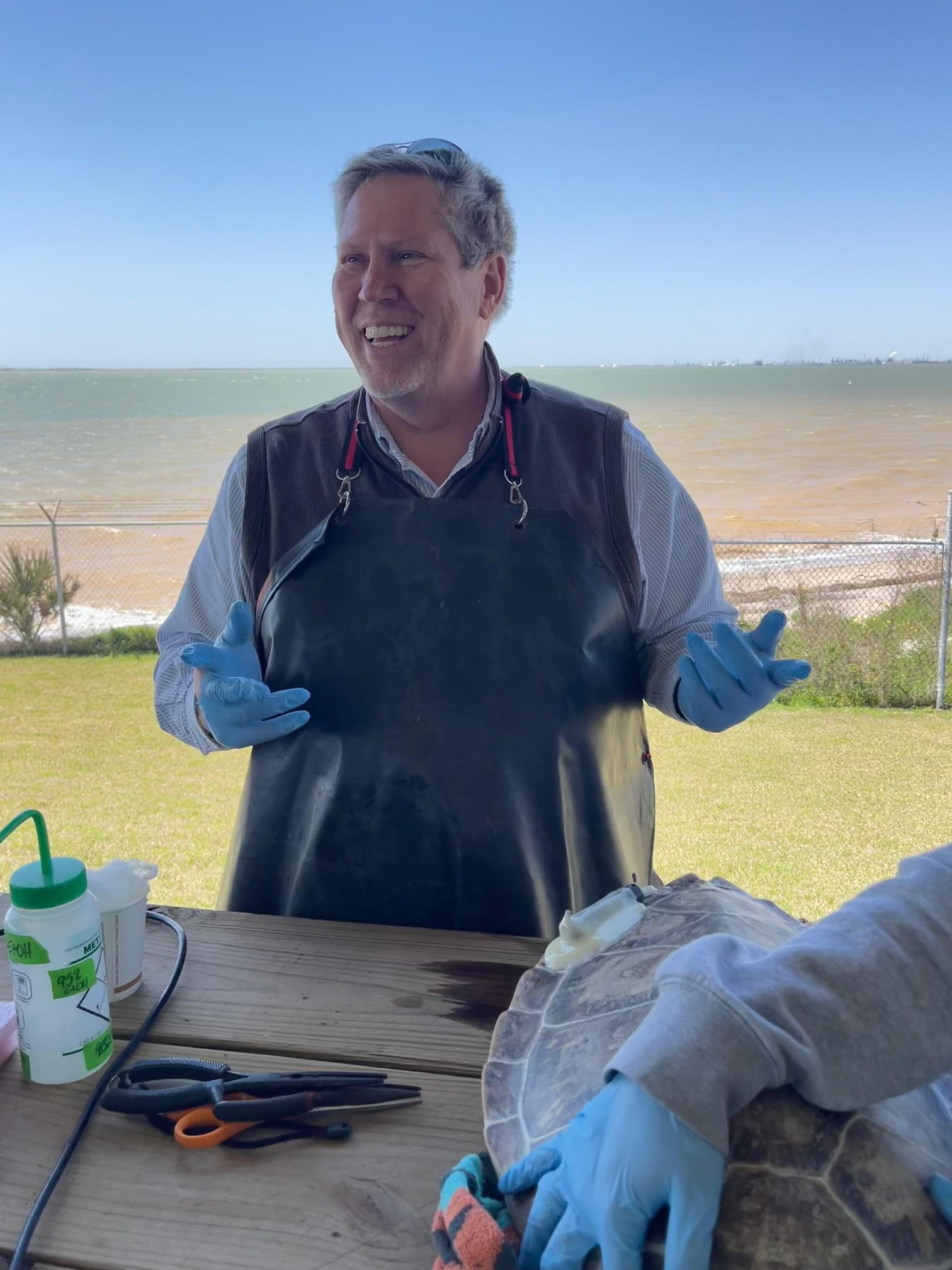

Marshall and his team collect data for their research. Provided by Christopher Marshall

He hypothesized it could be the strong bite force of loggerheads. “One of my specialties is feeding biomechanics. I was very interested in how hard loggerhead sea turtles bite. In Galveston at the NOAA facility we used to have a whole bunch of loggerheads…and Ben Higgins, who runs the place said, ‘Hey, be careful of that loggerhead, they can take your finger off.’ I found that alarming but also really interesting,” Marshall said.

After discovering that there was no data on the subject he made it his mission, stating, “That started me off on a long project in which we measured bite force in baby turtles, all the way up to large turtles — and they can take your finger off!”

His research set out to understand the bite force of loggerheads and eventually other sea turtles, and how they manipulated fishery hooks. An apparatus for measuring bite force had to be specially designed. This research eventually landed him in Mexico testing different methods of reducing turtle catches in fish netting operations. It was also a perfect opportunity to continue collecting bite force data from loggerheads and green sea turtles.

Marshall packs up sea turtle eggs before sending them to an incubation facility. Data has shown the excavated nests have a higher hatching rate than those left on the beach. Provided by Christopher Marshall

Marshall’s work then took him to Japan measuring bite force, performing flipper and satellite tagging, as well as data metric collection and subsequent release of turtles back into Japanese waters for radio tracking.

The information collected from the bite force study can now inform future engineering of fishery hooks to reduce bycatch. This type of simple science alchemized into applied science is at the heart of Marshall’s passion for his work.

A stint in Qatar rounded out globe-trotting adventures for the turtle expert. Many migratory species of sea turtles drift with the Gulf current into UAE waters where sand deposits along the northeast coast provide feeding and nesting areas. Marshall was invited to collaborate on a sea turtle conservation program in the country, training local biologists in sea turtle biology and studying movement ecology.

No place like home

While exotic locations are alluring, Marshall is experiencing the highlights of his career in his own backyard. Although TAMUG has been involved in sea turtle research since the 1980s he saw a huge opportunity for growth. “As I came back to Texas what I realized was that after all my travels and working in Florida [where his career began] … we didn’t have a lot of sea turtle biologists. We didn't have a lot of research infrastructure to do the work and just not a lot of attention to sea turtles in Texas at all. I did notice in the 20 years I’ve been here we have more sea turtles than ever in Texas.”

A volunteer carefully handles a turtle while data is collected. Provided photo

This growth has been seen most notably in the endangered green sea turtle population. The herbivorous green sea turtles are moving northward up the Texas coast, following seagrass beds that are their primary food source. While new seagrass beds are creeping northward as a result of rising temperatures, expanding rapidly disappearing sea turtle habitat is a positive.

Seeing the opportunity before him, Marshall took action. “I talked to our administration and I created a research center here at Texas A&M called The Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research. The idea was to bring attention to Texas sea turtles as well as Gulf of Mexico sea turtles … really trying to create a new sea turtle program on this part of the Gulf of Mexico,” he said.

In recent years NOAA has backed off from their sea turtle involvement and The Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research has stepped in. “Now, we are the lead for sea turtle rescue and strandings on the beach. We also got a grant to create a small, short term sea turtle hospital on campus,” said Marshall.

The hospital has been instrumental in turtle rescue efforts. Like the ones necessitated by winter storm Uri in February 2021.

A turtle has time to recover at The Gulf Center for Sea Turtle Research. Provided photo

Sea turtles are cold-blooded; however when water temperatures fall below 50 degrees they become cold-stunned — catatonic and unable to swim — and risk hypothermia, pneumonia and death. The historic cold front swept from the Gulf to the Northeast and resulted in a rescue effort to save 2,000 cold-stunned turtles. It also provided research opportunities for understanding behaviors that enable survival in extreme conditions.

Expanding healing and connection

Throughout the expansion of the sea turtle program at TAMUG there has been an outpouring of community support. In addition to the successful volunteer program, TAMUG has partnered with the Houston Zoo in providing medical services when needed.

Building upon these successes, Marshall said, “Now we’re trying to go even further and build a new building that will be an educational outreach facility with a larger hospital — which will be a place where the public can come and see sea turtles, learn about sea turtles, and help to support our programs through eco-tours.”

The expansion of the sea turtle program at TAMUG has made it the lead for sea turtle rescue and strandings on the Texas coast. Provided by Christopher Marshall

According to TAMUG, “The proposed facility will be approximately 23,500 sq. ft. with two hospital wards, a veterinary clinic, overnight facilities for care-takers, resident turtle tanks, auditorium-presentation room, media room, numerous educational outreach exhibits and a gift shop … A series of holding tanks will be placed outside of the hospital wards to hold healthy turtles that cannot be released into the wild. Visitors will have the opportunity to observe sea turtles up close. This will be the only place to do so on the upper Texas coast.”

While local residents can volunteer, report turtle sightings or order a state sea turtle license plate, anyone can follow the center on Facebook or donate to the cause.

The Upper Texas Coast Sea Turtle Hospital and Educational Outreach Center will be a place of learning and healing; it will also be a place where locals and tourists alike can personally observe and connect with these beloved and prehistoric creatures — a species essentially unchanged for 110 million years.