As Epitacio Franco fed another long rod of sugarcane into the mill with his cracked, weathered hands, he reflected on the changes in his community. The countryside, he explained, is emptying out. Young people are leaving for the big cities, and with them go traditions like sugarcane milling.

But on his farm on the top of a remote mountain near Concepción, Colombia, Epitacio and his family are hard at work preserving their traditions and passing them down to the next generation.

Just a few feet away, his 15-year-old grandson David tended to the underground oven. While David kept the fire burning, Epitacio and his wife, Doña Ines, stirred the freshly pressed cane juice into a boiling, thick caramel in huge iron pots. Together, the grandparents-grandson trio were making panela.

Pueblo of Concepcion, Antioquia, Colombia. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

Panela, also known as jaggery, is unrefined cane sugar. Unlike regular white sugar, which is heavily refined to remove all impurities and color, panela is made by boiling down sugarcane juice until it solidifies, keeping much of its natural richness intact. It has a deep caramel flavor, a golden brown color, and a fudgy texture.

Because it’s unrefined, panela also retains small amounts of minerals like calcium, potassium, and iron. In many parts of Latin America, panela isn’t just a sweetener; it’s a cultural staple, stirred into coffee, used in traditional desserts, and woven into everyday life.

Sugarcane grows fairly quickly after being harvested. Usually within 10-16 months after being chopped down, sugarcane regrows from the roots left in the soil after cutting, making it a renewable resource. The giant stalks of sugarcane often crow alongside cacao trees, banana trees, papayas, and coffee plants. All of those crops help each other by sharing shade and nutrients.

The family’s sugarcane mill and farm, only reachable by foot or horse. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

In the mountains of rural Colombia, there are small towns known as pueblos that have homes, a plaza, church, and stores. But oftentimes in the countryside surrounding those pueblos are communities known as veredas.

Veredas are collections of scattered farms, houses, schools, and a lot of open land. People who live in the countryside and make a living off of their agricultural land, crops, and animals. They live in harmony with the mountains and the rivers, away from civilization. So far away that sometimes they aren’t accessible by road or vehicle, only by foot or horseback.

In these veredas, many families grow crops like sugarcane, bananas, cacao, and coffee. They are small operations who band together and help one another sell their produce.

Epitacio processing the sugarcane into liquid. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

During harvest season, the mill sends workers to different veredas to collect the sugarcane. Once the mill processes it, they sell and distribute the product to the town. Once paid, the mill keeps a small percentage then distributes the earnings among the contributing families. Each family is also compensated with blocks of panela.

The Art of Making Panela

Once the panela has boiled, workers stir it until it reaches a thick sticky consistency. This photo is at a different panela-making location, in Caldas. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

On production days, the work begins at 2 a.m. and continues for 12 or more hours until the final product is complete. The milling process is dangerous and demands extreme attention. Workers must be incredibly alert as they feed the cane into the mill—stray fingers can easily be lost.

Typically, the most experienced worker handles the task. In this case, it’s Epitacio, a 75-year-old who has spent his life mastering the process.

After the cane rods are pressed into juice, the liquid travels through a system of pots heated by an underground oven fueled with the leftover sugarcane husks. It’s a full cycle—nothing goes to waste.

The workers stir the juice for hours until it boils. As it bubbles and thickens, they move it between pots with huge spoons to prevent it from sticking. These scalding pots become dangerously hot, and accidents are sadly common.

Process of sugarcane thickening and being stirred for hours. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

“Conejo!” Epitacio shouted. A code word meaning “rabbit” in Spanish, but here it signals that the panela is ready.

The first thickened layer of sugar indicates it’s time for the next stage. The liquid is strained through wood and cloth, then poured into a giant, bathtub-sized steel container. Workers take turns stirring it with a paddle until it reaches a fudgey consistency, a task that demands intense muscle as the mixture thickens with every stroke.

Finally, it’s poured into wooden molds and left to cool. By the end of the day, disks of hardened, pure, unrefined sugar are ready.

Panela is poured into molds and left to dry and harden. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

A Cycle of Sustainability, Broken by Plastic

Traditionally, these blocks were wrapped in dried banana leaves and transported by mule to town. Today, while the mule transport remains (because there are no car-accessible roads to the farm), the panela must be packaged in plastic to comply with government sanitary regulations.

“While I’m proud that we still make panela by hand, I’m disappointed that the final product has to be wrapped in plastic,” Epitacio said. “Not only is it more expensive for us, it’s incredibly harmful for the environment.”

Panela wrapped in plastic versus panela wrapped the old fashioned way in dried banana leaves. (Photos: Maria Vargas)

It’s a sad contradiction: an artisanal process that is almost entirely sustainable: powered by mules, fed by natural waste, and crafted by hand, only to end with plastic waste.

Locals, who have bought panela wrapped in banana leaves for generations, don’t see the plastic as an improvement. Instead, they now find plastic bags polluting their rivers, trees, and roads—an environmental issue that could easily be avoided by returning to natural wrapping.

There’s no clear solution. It's the double standard of modernity: we claim sanitation over sustainability, even when the difference may be negligible.

Doña Ines and Epitacio hard at work. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

Weaving between the kitchen and the mill dozens of times each hour is Doña Ines, the farm’s matriarch.

“When we were a younger family, I was taking care of three kids, running the house, cooking breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks, feeding the animals, stirring the panela, and wrapping the final sugar blocks,” she said.

Doña Ines’s strength and spirit continue to keep the farm running in harmony. Today she is still seen keeping her small grandchildren in check while tending to the kitchen and helping Epitacio and David with the mill.

“Every day I walk to the town then back up here on the mountain,” she said.

It’s a journey that takes about two hours each way by foot or an hour on horseback. But she likes to visit the town to see her friends, get groceries (the food she doesn’t produce herself in her garden), and check on the panela sales. Despite her age, she is active, agile, and sharp.

Breakfast at the farm and fresh panela stirred into coffee. (Photos: Maria Vargas)

It takes a lot of work to maintain a farm, mill, and household, yet Doña Ines even makes time to host visitors. In a partnership with a local bed and breakfast hotel, La Finca De Los Abuelos, they bring visitors up to the farm on horseback to see it in action.

Doña Ines takes the lead in welcoming guests, cooking them the most delicious homemade breakfast with eggs from her chickens, homemade cheese, fresh arepas, and of course– coffee sweetened with panela. She even built a tiny home next to theirs if guests ever want to spend the night on the peaceful mountain.

Even the chickens share coffee time. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

The Importance of the Younger Generation

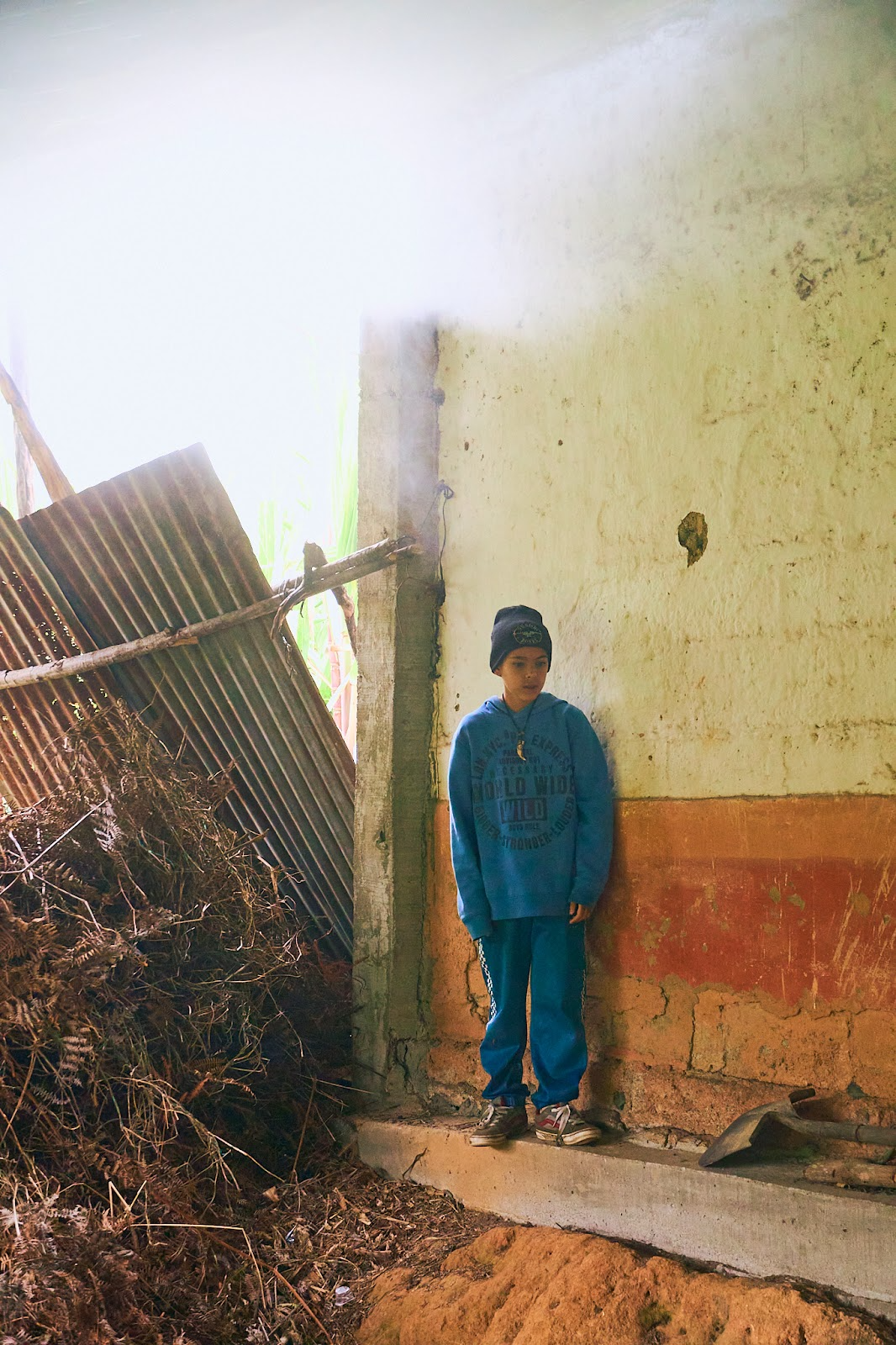

David is proud to help his grandparents run the mill. He’s an example of a young person balancing both worlds: pursuing an education while honoring his family and community’s traditions.

Too often, young people like David must choose between a lifetime of hard labor without getting an education, or the uncertainty of going to school and then moving to the big chaotic city.

“Most of my friends want to leave town and go to the city for whatever job they can find. But not me. I want to study—and also work to keep our community’s traditions alive,” David said. “The city is too loud, too many people, and far from nature. Out here we wake up hearing the birds and eating food we grew with our hands. It’s not an easy life, but it’s the one I prefer to live.”

Fifteen-year-old David tending to the in-ground oven while his grandparents stir the boiling pots above. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

David shows us that it’s possible to do both. Through a local program, he’s able to continue his education while working part-time at the mill. His dream is to maintain his family’s land, purchase more, and hire others from his community to work and thrive.

In the veredas, schooling often comes with the assumption that it’s of lesser quality than in the cities. However, the reality is that while rural schools may not have the same resources or technology as urban counterparts, the education they offer is uniquely adapted to the needs of the land and community.

Local guide’s son, watching the panela process. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

Students in the veredas learn not just math and science, but practical skills like farming, animal husbandry, and environmental stewardship, which are integral to their daily lives.

This hands-on, contextual learning shapes a different kind of knowledge—one that’s deeply connected to the land and local traditions, preparing them for a future that values sustainability and community as much as academic achievement. It’s a different education, but no less valuable.

What’s at stake if younger generations leave the countryside is the takeover of vast areas by industrial corporations, which often leads to severe environmental degradation, unsustainable farming practic(es, and the loss of traditional family practices. This is why it’s increasingly vital for pueblos and veredas to provide quality education that encompasses both traditional subjects and the skills needed to preserve local agriculture and customs.

A horse feeds on the mountainside. Horses remain the main source of transportation for the veredas. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

According to conversations with Epitacio and Doña Ines, they said if we want small towns to thrive in the future, they believe the younger generation must be taught both academic subjects and the vital practices that sustain their communities. To them, this is the path to financial stability, environmental stewardship, and a high quality of life.

Doña Ines’s guesthouse. (Photo: Maria Vargas)

Cities like Medellín, the closest large city to this pueblo, are becoming overcrowded, with rising costs of living and a highly competitive job market. While life in the veredas is not without its challenges, it offers a slower, more harmonious pace.

Families like David’s are determined to create opportunities and livelihoods in their own communities, ensuring that their veredas and pueblos continue to flourish.

David’s story gives the countryside hope. Not just because of his own determination, but because of the support he receives from those around him. “Having a supportive family and a school system that allows me to study and work…that’s everything. It allows me to stay in the place I love and work toward making it a better place for our community,” he shared.

It’s a reminder that the future isn’t something distant waiting to arrive; it’s already being created, every day, by people like David and the families who believe in them.

Author Maria Vargas on horseback at the farm. (Photo: Maria Vargas)