Inspired by a lifetime of studying the tenacity of the wild things that persist amidst challenging conditions, author and horticulturalist, Eric Lee-Mäder, sheds new light on a persistent plant that is finally being appreciated after decades of disdain.

In his book, The Milkweed Lands, Lee-Mäder goes beyond the well cited relationship between the milkweed and the monarch butterfly and delves into what’s happening above and below the soil in ecosystems where milkweed is found, and also explores the plant’s often overlooked cultural and historical significance.

With the rich text set alongside bountiful botanical illustrations by the artist Beverly Duncan, The Milkweed Lands is designed to be a multifaceted tapestry that can be appreciated by audiences of varying ages and interest levels.

Recently, KINUTE caught up with the author to discuss the book, his buzzing native meadow business, and his lifelong interest in the wild things around him.

Why did you originally want to write The Milkweed Lands?

Among the wild plants of North America, milkweeds have long occupied an interesting place in human culture. Native people have ancient ethno-botanical relationships with these plants, but for most of the past century, American culture has held these plants in low regard.

Even as milkweeds feed monarch butterflies, which most people find beautiful—or at least interesting—and despite the fact that we have used milkweeds for vital industrial products—they have mostly been considered contemptible weeds that should be banished from polite spaces.

We've waged chemical war on them in agricultural fields, and fined people for growing them in their yards. Yet milkweeds have continued to persist in places that make us uncomfortable such as vacant lots, trash-strewn roadside ditches, and along desolate railroad tracks. This kind of unruly wildness is something that feels quite rare and almost mystical to me, and it's what inspired the title.

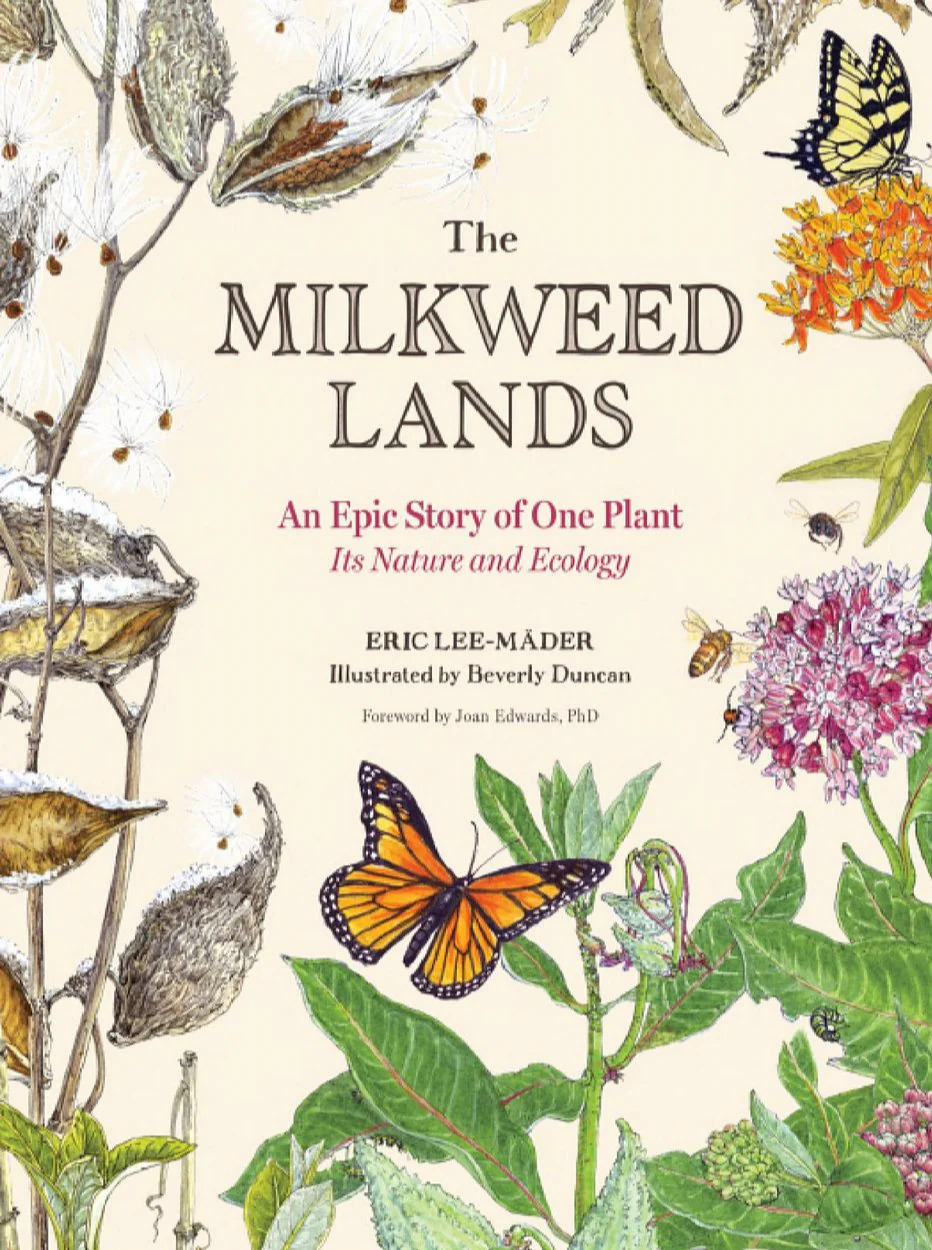

The Milkweed Lands is more than a story of a plant, it's the story of the mostly unnoticed co-inhabitants of those lands where the plant grows.

Milkweed Feeders illustration from The Milkweed Lands. (Courtesy of Eric Lee-Mäder)

How does this book go beyond the well documented relationship between milkweed plants and monarch butterflies?

There is often a sad irony in the fact that the wild things that co-exist with us most tenaciously are the wild things that we tend to be least fond of. Lots of non-native organisms fall into this category: carp, starlings, dandelions; but quite a few native organisms also experience this same indifference and sometimes loathing: possums, spiders, and historically many prairie plants, especially milkweed.

As milkweed is now beginning to gain mainstream respect and admiration—both for its relationship with monarch butterflies as well as for its intrinsic beauty and character—it felt like a good vehicle for looking deeply at this issue. Loved or loathed, milkweed has a natural history that connects life in the soil to life in the clouds. In milkweeds we see an almost infinite universe of associations from fungi that require milkweed to survive, to tiny leaf-feeding insects (and even smaller parasites of those leaf-feeding insects).

With milkweeds we see plants engaged in constant chemical opposition to animals that adapt to that chemical opposition, and other animals that eat those animals, and the struggle plants have to spread their seeds and share their genes among distant populations. My hope was that by telling this story about milkweeds, that people might look just as deeply at all of the other tenacious wild things that we oftentimes dismiss for their commonplace tenacity.

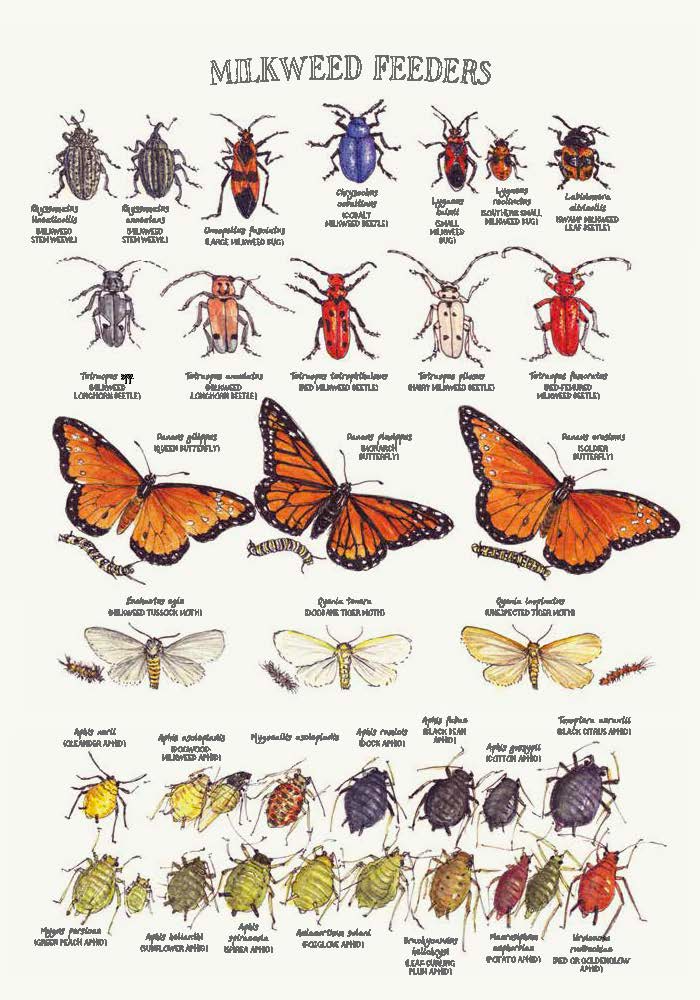

Milkweed pollination illustration from The Milkweed Lands. (Courtesy of Eric Lee-Mäder)

How did the final product differ from the book you originally set out to create?

Believe it or not, The Milkweed Lands started as a children's book with the working title of Milkweed Hotel. It was intended to feature the various insects that rely on milkweeds for occasional food and housing. It quickly became clear however that there was such a complex and diverse natural history associated with milkweeds that it would be a challenge to contain the topic in a short picture-book format.

As a result, what Beverly Duncan (the incredible illustrator), and I tried to produce, was a book that a reader of any age could pick up and leaf through—reading deep into the text, or simply looking at the illustrations. In a way it still functions as a children's book, as much as it functions as a meditation on the role of these wild plants in an almost completely human-altered world.

Can you tell us about your career outside of being an author?

In some distant past, I was a high school drop-out, film projectionist, UPS package sorter, audio cassette duplicator, janitor, dishwasher, dot com marketing executive, and various other things. Much of it was unsatisfying work.

Sometimes I would sneak out of these various jobs and just go for a walk to escape the tedium and confinement, looking at the various birds and weeds that I might encounter. It wasn't until I was around 30 that I realized I should see if I could construct some kind of new occupation around nature, so I sort of conned my way into a grad school program in commercial horticulture, and got a student technician job at the university's bee lab. That lab would occasionally feed me and pay me and all I had to do was get stung a thousand times a day.

When I emerged with a degree, I did freelance crop consulting for a group of prairie grass seed producers in the Midwest, and then ended up as a pollinator conservation director at the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation just as pollinator declines became a mainstream issue. Xerces was at the forefront of working to understand and take action to address those declines and it was an extraordinary testing ground for new approaches to native plant restoration.

Before retiring from Xerces in 2024, my team and I managed a habitat portfolio of around a quarter-million acres nationwide—including everything from enormous mile-long native shrub hedgerows in California, to prairie restoration projects in central Canada. It was at Xerces, more than a decade ago, that I had a chance to dive deeply into milkweed propagation, partnering with nurseries in Florida, Arizona, Texas, New Mexico, California, and Nevada to research how we could mass produce some of the more uncommon milkweed species in those regions for monarch butterfly habitat restoration.

A vibrant native plant meadow amidst an urban backdrop. (Courtesy of Eric Lee-Mäder)

What inspired you to start Northwest Meadowscapes?

Meadows, prairies, and grasslands—which are all essentially the same thing—are intrinsic to the human experience. They are the original ecosystem that we emerged out of, and one that still deeply resonates with all of our senses. I have always felt a strong pull towards the undergrowth of meadows and the wonders and dramas that unfold within them—the small creatures, the hidden orchid—the entire miniature universe.

While I had professional experience in meadow plant production and meadow restoration at Xerces and elsewhere, I was also constantly creating and fiddling with my own meadows whenever I moved into a new house with a yard. Initially my wife and I had the idea to simply sell a few packages of meadow seed that we were growing at home.

Everything really snowballed from there, eventually leading us out of the city, farming meadow plants, and trying to support other people creating their versions of these fantastic spaces.

Why are you drawn to native plants and pollinators?

I grew up poor—single mother, small town, Midwest, basement apartment, poor. Other kids had sports and vacations. I had polluted creek bottoms and abandoned cars in the forest.

While not at all pristine, the natural areas surrounding me provided a kind of refuge from stress and precarity. And because I spent so much time hiding away from my circumstances in nature, I could, from a very early age, discern the different types of trees and insects that were my closest associates.

It sounds odd to say, but I suppose that growing up, I associated natural things sort of as family members, and I suppose I still do today. It's comforting in a way to find familiarity and companionship in things like aphids or acorns, but also complicated to interact with the world when you feel like these things are your equals.

Native wildflower meadow. (Courtesy of Eric Lee-Mäder)

What gives you hope in the work that you do?

I think a lot about what it means to be a wild thing when so much of the planet has been directly altered by humans. In that context, where exactly does one find wilderness and wild animals? Certainly there are pristine arctic rivers and Sumatran tigers and incredible remote tropical coral reefs, but can the average person access that kind of nature? And if they could, would any of that nature survive the intrusion?

An alternative that we often overlook is the wild world that persists in the shadows all around us—the epic sturgeon and paddlefish that still swim our muddy industrial rivers alongside barge traffic, the raccoons and coyotes that roam city streets at night, the leafcutter bees and great golden digger wasps that make their homes in our backyard gardens, the swifts and bats that nest in abandoned chimneys.

The quite remarkable thing is that even modest efforts at making habitat, such as planting your front yard with prairie plants, or constructing a mini-forest of native flowering shrubs and fruit trees can have outsized impacts on supporting wildlife.

As an example, a few years back I worked on a de-paving meadow project in the middle of Seattle. It is a little smaller than a city block and surrounded, literally, by dozens of square miles of concrete and adjacent to major arterial streets.

Within a year of getting the meadow established it was supporting rabbits, an owl, a rare bumble bee species, grasshoppers, and a nesting pair of white crowned sparrows. People all over the country are doing work just like this, often in their own home spaces. And every one of those projects is its own magnificent story.

What’s currently on your professional horizon that you’re most excited about?

I'm currently working on a very large project related to wild lawns. For context, these are diverse, typically flower-rich assemblages of native grasses and wildflowers that can be mowed occasionally, walked-on, and function mostly like a regular lawn, while also supporting a stunning amount of natural life. There has been a sublime movement toward replacing lawns with meadows, and the wild lawn concept aligns with that movement.

However the concept of a wild lawn focuses specifically on low-growing meadows which preserve some of the functionality of a lawn, while avoiding some of the challenges with taller meadows—such as fire risk, community expectations around safety, and sight lines.

For the past century we've lived in a dualistic paradigm of lawn obsessives and people who mostly ignore their lawns. However, I think the time is emerging for a new category of people, lawn ecologists.

The Milkweed Lands Author Eric Lee-Mäder. (Courtesy of Eric Lee-Mäder)