In March of 2017 biologist Sara Dykman set off from central Mexico to accomplish something that had never been done before—to bicycle the entirety of the monarch butterfly migration route along with the four generations of winged warriors it takes to complete the 10,000-mile journey.

In December of that same year, Dykman and the monarchs returned, victorious, to the El Rosario overwintering colony in Michoacan, Mexico.

In the wake of this incredible accomplishment, Dykman has founded a pioneering research project in Mexico and authored a book, Bicycling with Butterflies, about her journey.

A book, which Dr. Jane Goodall says is, “An extraordinary story in which Dykman seamlessly weaves together science, a real love of nature and the adventure and hazards of biking with butterflies from Mexico to Canada and back.”

Counting Monarchs

The research project, Counting Monarchs, prides itself on employing local women who live near El Rosario to record the streaming behavior of the butterflies three times daily.

Streaming behavior refers to the flights monarchs take up and down the mountainside on warmer days. Typically, overwintering monarchs are relatively inactive to conserve energy. It is thought that streaming behavior may be due to the butterflies searching for water, jumpstarting their reproductive system by increasing their metabolism, or for purposes yet unknown.

While much about this behavior remains a mystery, the work that Counting Monarchs is doing is of tremendous importance in establishing a baseline dataset.

Founded in 2020, Counting Monarchs has evolved to employ nearly two dozen women, include use of specialized equipment, and gather increasingly more data targeted at answering questions about streaming behavior and how climate change may affect it.

Monarch laden trees at El Rosario Preserve. Photo courtesy of Sara Dykman

While it is hard to imagine a butterfly as having any body fat, and that they could amass this much needed reserve during their incredible migration, they do. It is known that these fat reserves sustain them throughout the winter and that streaming behavior burns calories.

As climate change will likely bring more warm days to the region, there is concern that increased activity could put the monarchs at risk of starvation before completing their return flight north in the Spring.

“The long-term goal is to establish a program that will continue to monitor streaming monarchs as a way to support local women, create a conservation economy, and determine trends and changes in streaming behavior,” Dykman said of Counting Monarchs.

“The best way to protect the forest in Mexico is to offer the people living nearby incentives to be stewards.”

Indeed, it is the monarchs that Dykman wants to live on, not her bicycling accomplishment.

Beyond a book

While the achievement is inarguably noteworthy, it was not Dykman’s first odyssey for environmental awareness.

In May of 2010, Dykman and a dedicated team set out for a year-long adventure to bicycle 49 states (all but Hawaii), covering more than 15,000 miles. Dykman knew that she needed the year to have a deeper focus, in order to abate boredom. The friends came up with the idea to speak at schools along the way.

In total, the crew spoke to over 7,000 students on their first education-linked adventure. The focus of their presentation was on the diversity of the United States, the joys of traveling by bicycle, and the benefits of a healthy lifestyle for a healthy planet.

Members of the Bike49 crew in Alaska. Photo courtesy of Sara Dykman

The organization is known as Beyond a Book—an acknowledgment that going beyond book learning and into the realm of experiential learning holds transformational potential.

“The purpose behind all of these [adventures] is to get people learning with hands-on experience and not be afraid to make mistakes,” Dykman said.

“If I had waited until I was an expert at monarch biology then, I would never have done the trip, because the only way you can really learn is taking a step out—just being outside, learning as you go, talking to people, observing.”

Following Bike49, as their inaugural journey came to be known, the Beyond a Book team took to the water for their next trip—traveling from Triple Divide Peak in Glacier National Park, Montana to the Gulf of Mexico via the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. This time, they not only engaged students in classrooms along the way, but also on river field trips, putting experiential learning into practice.

Next up, the crew headed to South and Central America, bicycling nearly 10,000 miles through 12 countries on their journey from Bolivia to San Antonio, Texas.

Bicycling in Peru. Photo courtesy of Sara Dykman

ButterBiking

Historically, Beyond a Book adventures have been team endeavors. However, as fate would have it, following the monarch migration, or ButterBiking as she coined it, would be Dykman’s first solo-expedition of this magnitude.

Dykman, whose primary career focus is amphibians, was attracted to the venture for a variety of reasons. In addition to the migration moving at a pace that is well suited to bicycling (about 60 miles per day), she loves their accessibility.

“You don't have to be a biologist to be able to recognize them. You don't have to be a rich traveler to go visit them. All you have to do is plant a couple plants in your yard and they'll come visit you,” she said. “They're just familiar enough that they feel like a friend.”

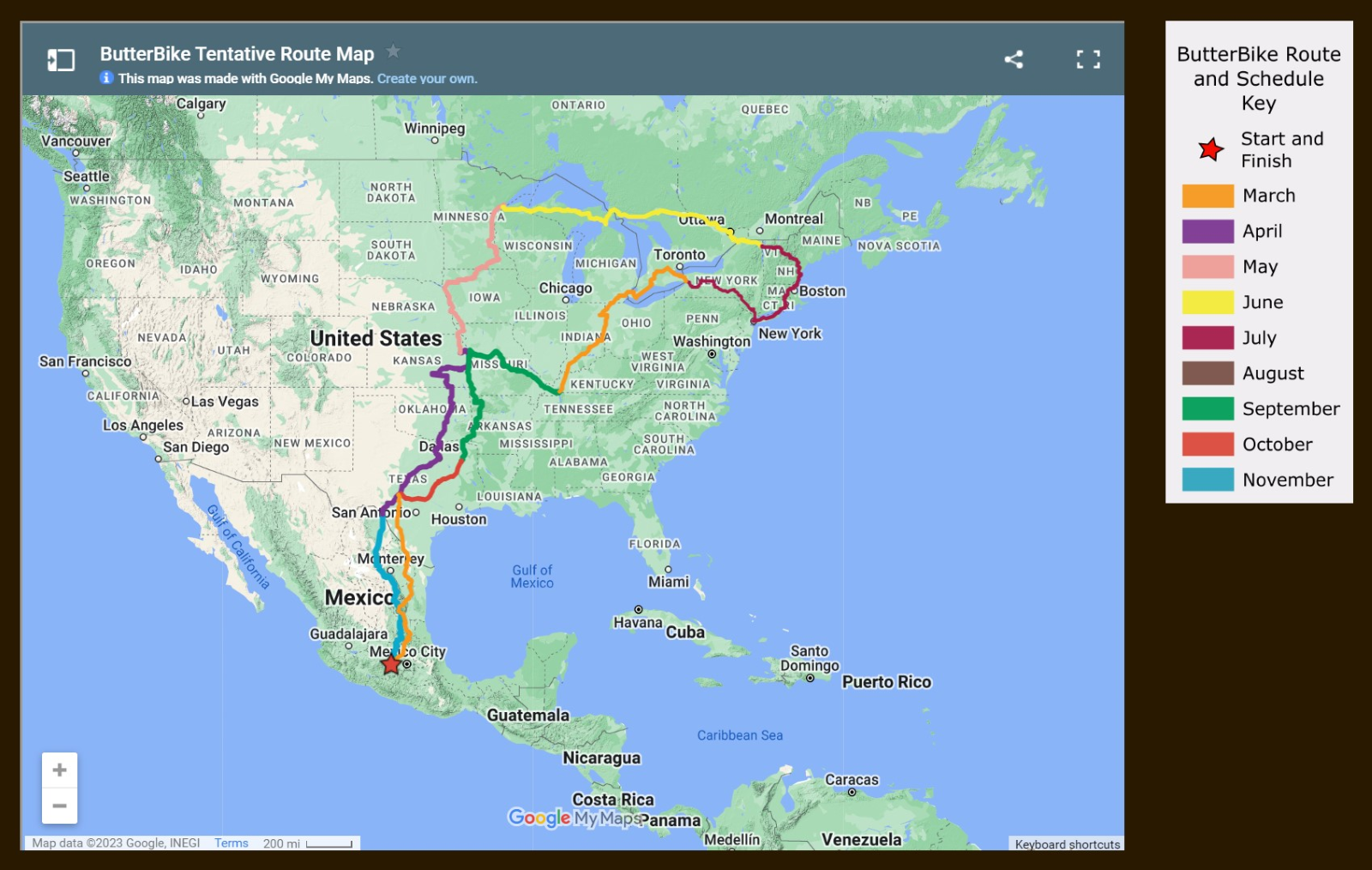

Annual monarch migration map

Sara Dykman’s bicycle route

While the daily reality of her ride did not entail seeing droves of monarchs, she found herself tuning into their habitat, spotting and stopping for the milkweed that is essential to their survival.

Milkweed is the only plant that monarchs will lay their eggs on. When the fact that it takes three to four generations of monarchs to complete one successful roundtrip migration settles in, it becomes alarmingly clear that milkweed is needed everywhere.

Dykman spots a milkweed with a monarch caterpillar | Photo courtesy of Sara Dykman

As she rolled along, her keen eyes trained on the roadside scanning for the milkweed that is imperative to their survival, it seemed impossible not to notice all the habitat that had been stolen from butterflies. This, coupled with the anecdotes she continuously heard along the way from older generations confirming a visible decline of the species, stoked an anger inside her.

Yet, Dykman came to realize that it’s okay to be angry and took it as proof that she was paying attention to the monarch’s plight. She also knew that an antidote to this anger was action—which she has taken in spades. The good news is that everyone can help and that the effects of action tend to spiral out and grow.

A monarch-friendly yard. Courtesy of Sara Dykman

“It really just takes sharing a little bit of your yard and a little bit of the yard at your library or church or school,” Dykman said. “You don't have to know what you're doing. You just learn as you go."

While she witnessed disheartening things, like habitat loss and complacency, along the way she also met a legion of allies who bolstered her spirit. These are the people who have chosen to exemplify another way.

“There are so many people fighting back against homeowner associations that say no milkweed or city ordinances, and that's only because people have an example,” Dykman said.

More than anything, she said, “If we can be that example, go be it.”

Dykman doing amphibian field work. Photo courtesy of Sara Dykman