Throughout her 17-year career as a travel writer, Jane Marshall has ventured far and wide to some of the most remote places in the world.

In the course of her journeys—often at high altitude far away from the usual tourist path—she stumbled upon a revelation. Across three continents separated by vast oceans, she encountered enigmatic valleys affectionately referred to by the locals as "Happy Valleys." Intrigued by the notion of happiness within these secluded enclaves, Marshall embarked on a quest to unravel their secrets and glean wisdom from the Indigenous communities that safeguarded them.

Jane Marshall reaches Larkye Pass on the Manaslu Circuit in Samagaun, Nepal. Provided photo

Kinute spoke with Marshall about her new book “Searching for Happy Valley: A Modern Quest for Shangri-La,” where she explains the transformative power of these Happy Valleys and challenges us to reimagine our relationship with nature and each other.

Q: What is a “Happy Valley” as you define it in the book?

A: A Happy Valley is a place that is remote and protected by mountains, where life is deeply connected to nature. Within them, “happy” doesn’t necessarily mean that everything is comfortable and perfect all the time. It’s more about accepting the ups and downs of nature, and finding joy in the reality that all things change. All things have seasons. All things live and die.

A "wild camp spot" on the spur. Marshall's orange tent, with the glacier, is pictured on the left. Provided photo

I like to use the word "un-sanitized," meaning that Happy Valleys are wild, free zones where humans and nature have struck a balance, or we could say, formed a relationship. So often humans manipulate the natural world to the point where it’s unrecognizable. We raze it, pave it, drive out the animals and only then call it home. That’s not the case in these Happy Valleys. There, nature rules.

Camp 2, Sarphu. Views of Ganesh Himal bordering Tibet. Provided photo

What are the characteristics that link these Happy Valleys?

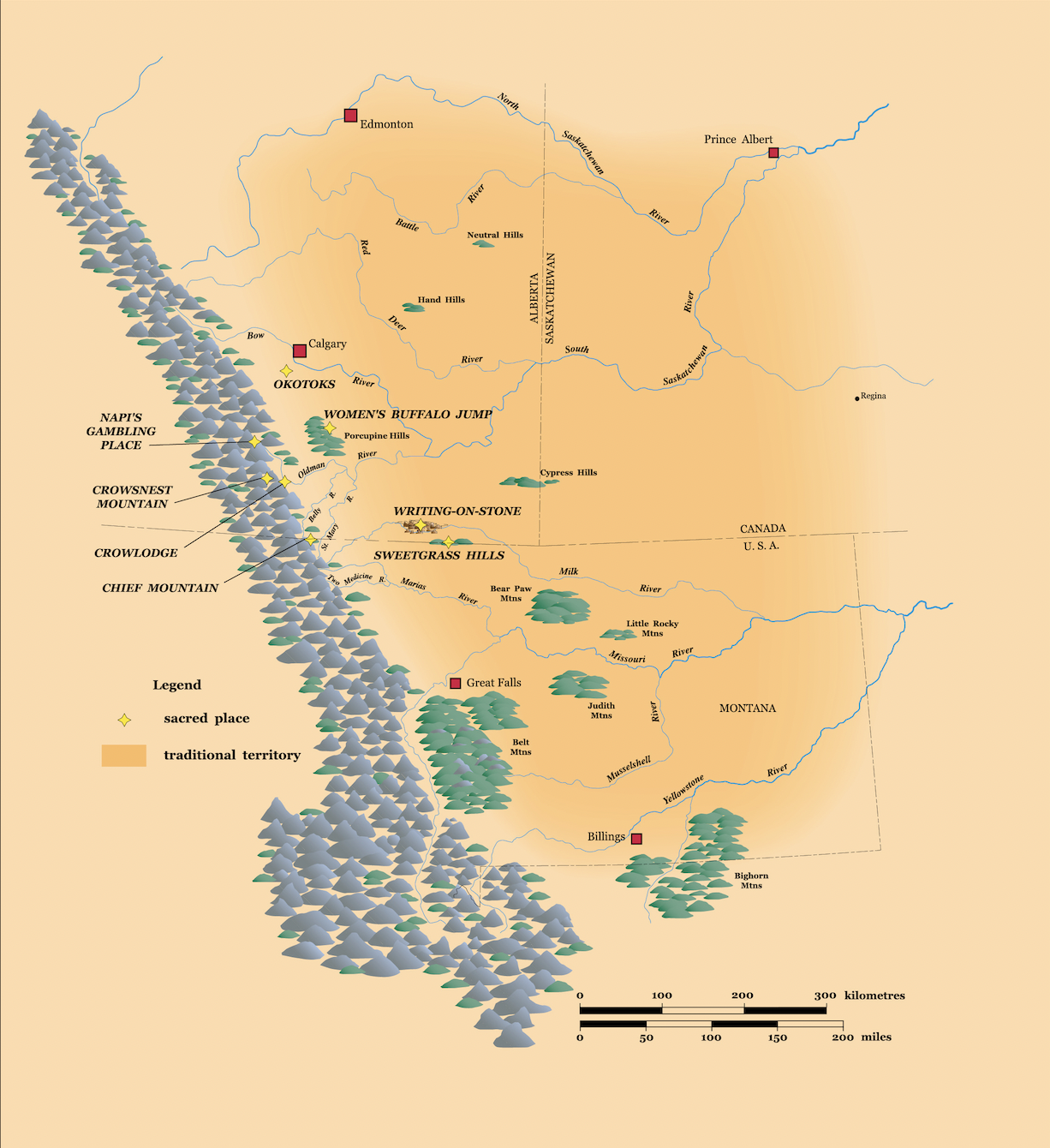

The valleys are home to rare plants and animals, and rich Indigenous culture. Women of these cultures tend to be revered as a powerful and balancing force, as in the Blackfoot/Soki-tapi First Nations of Alberta. Something else really caught my attention, and was cross-cultural in each valley; geographical locations were named after body parts. For example in Alberta, we find the form of the Blackfoot/Soki-tapi Creator Naapi spread across the land. The Rocky Mountains are his spine, the Porcupine Hills are his ribs, his heart is in the middle and his nose is in what we call Calgary in present times.

Traditional Blackfoot/Soki-Tapi Territory. Courtesy of the Glenbow Museum

In Morocco a village we visited was called “Head and Shoulders,” and there was a mouth in the Happy Valley there too. And in Nepal, at the secret center of Happy Valley, I found a cave with an opening representing female anatomy, and a rock outcropping in the form of a female Buddha in the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon (plus many, many more).

These cultures on three different continents see themselves, and the sacred, in the land. Imagine if we all did? Maybe the so-called modern world would be less keen on harvesting the land if we saw ourselves in it …

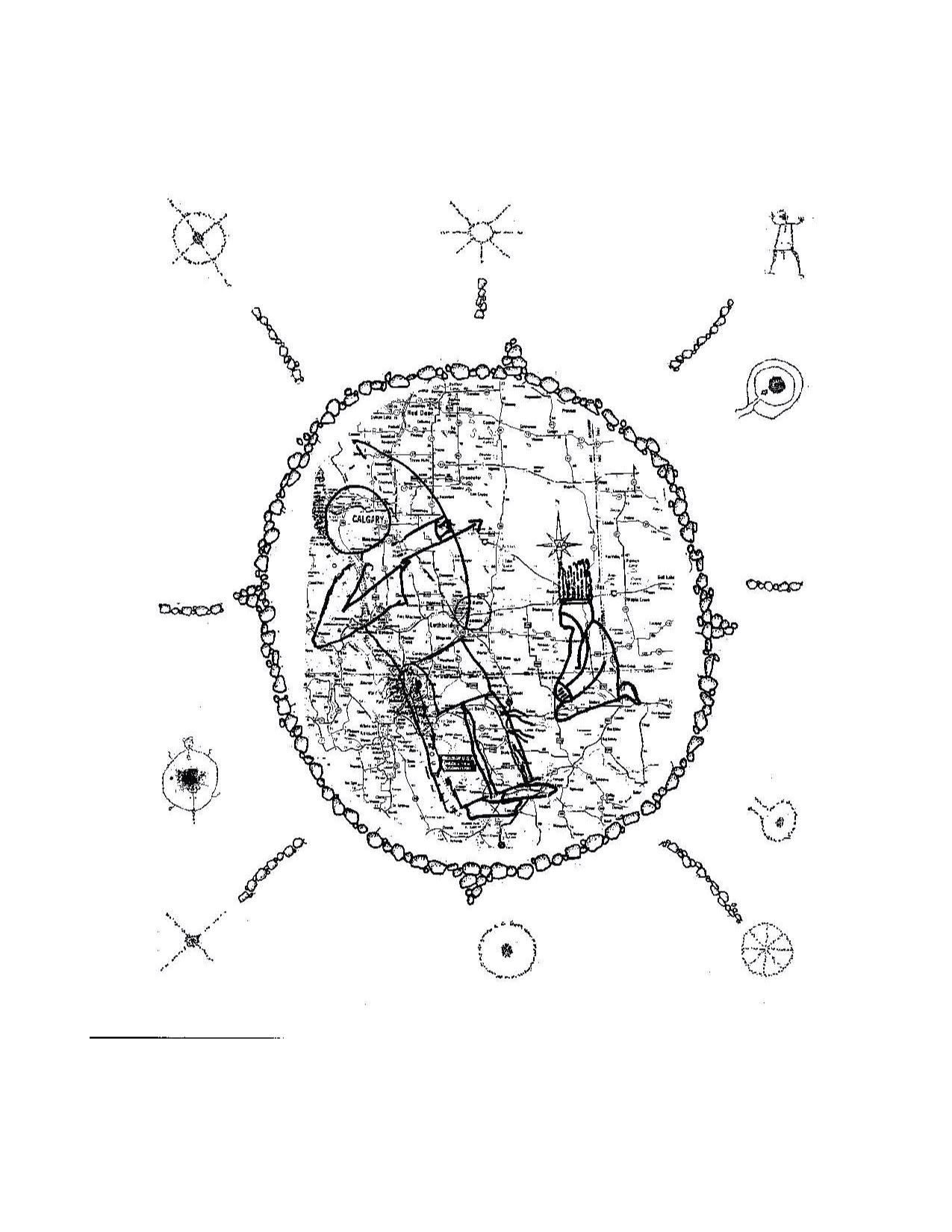

Nāāpi and the Old Woman. Map drawn by Stan Knowlton, head interpreter at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump/Pissk’ān, as experienced in his Vision Quests. Courtesy of Stan Knowlton

What is the link between human happiness in these areas and the wellbeing of the environment?

The link is tangible. In Morocco, ancient farm plots of the Amazigh/Berber people have existed for generations. The villagers work as a community whole tending the land, forming hand-made irrigation canals to nourish their food crops and moving goats around. The land is never over-used, because if it was, they couldn’t survive year over year with their subsistence lifestyle. Their homes are built from stones and mud pulled directly up from the valley walls. There is a joy and satisfaction there beyond description. Our guide and friend Ahmad, who splits his time between the city and valley, told us that when life gets too busy and crazy, it’s Happy Valley that he longs for.

Marshall's guide, Ahmad, shows her family his homeland in Ait Bougemez. Provided photo

In my home province of Alberta, Indigenous peoples have faced genocide. They endured horrific realities that occurred right here in Canada, including torture in residential schools. I attended a Sundance Ceremony and Sweat Lodge Ceremony on their land, and discovered that they connect with Earth and spirit in order to heal and find happiness. I felt it too—a deep connection to the Earth, and the Earth’s base nature feels good.

The north end of the ridge near Senge Dongpa Chen. Lingering in the sunset, with the glacier below. Provided photo

In the Himalayas, you can look at the open smiles of the people and see pure happiness. Life is hard. Subsistence farming, semi-nomadic camps to feed yaks on summer grass, no road access at all—yet there is so much joy. The people I’ve brought to Tsum, Nepal from around the world through my trekking company are deeply moved by the joy they feel there themselves. It’s in the mountains and valley, and it emanates from the community. Trekkers often say being in the Happy Valley of Tsum changes their lives forever.

Conrad Little Leaf/Piita Piikoan at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump/Pissk’ān. Courtesy of Roth and Ramberg Photography

Can you discuss the role of your grandfather in the genesis of your spirit as a traveler, and writer?

Mmmm. Yes. My grandpa was a bit of a wanderer, always looking for a place to set his roots. I’d observe this longing in him, and would sometimes go with him on hikes or drives to very quiet places in the mountains. Because he was a quiet person, I had the chance to think and observe. So often we fill space with language and words, then miss the intricacies of our environment. Grandpa definitely gave space for silence. He was happiest in quiet, remote places, and so am I. That space is also the space where my creative mind can play.

Ani Pema looking up the valley to the Sarphu River. Provided photo

How did populations in these areas relate to more populous, bustling parts of the world?

In Morocco, our guide Ahmad explained that many Amazigh/Berber nomads and villagers are moving to the cities because life is easier. Yet something was lost in that move—the connection to land and ancestry. Ahmad said there was more "solidarity" in the mountains. He manages to live in both worlds.

A high view of Ait Bougemez, above Ahmad’s family’s guest house. Provided photo

In Alberta, the Blackfoot/Soki-tapi people live on reservations and in cities, and have a complex and painful history with Canada. There is still a lot of racism toward Indigenous peoples and a lot of healing to do. It would be an excellent question to ask these communities directly. There’s still an unfortunate divide between many Indigenous people and the rest of the country. Something here must change, and I’m hopeful that it will as we evolve as humans.

Ani Pema making noodles at Drephuet Dronme Nunnery, Tsum. Provided photo

In Tsum, Nepal, there is no road access, though a road is currently being built. The culture was largely isolated until 2008 when trekking opened in the region. Most kids must leave their mountain homes and go to Kathmandu for school. It’s often a huge culture shock moving from the remote, quiet environment of Happy Valley to the polluted city of Kathmandu. Of course most people are keen to get wifi and connect with the global community as well! The relationship between Tsum and the outside world seems to be evolving at turbo speed, but luckily there are some extremely intelligent and wise local leaders navigating rapid changes.

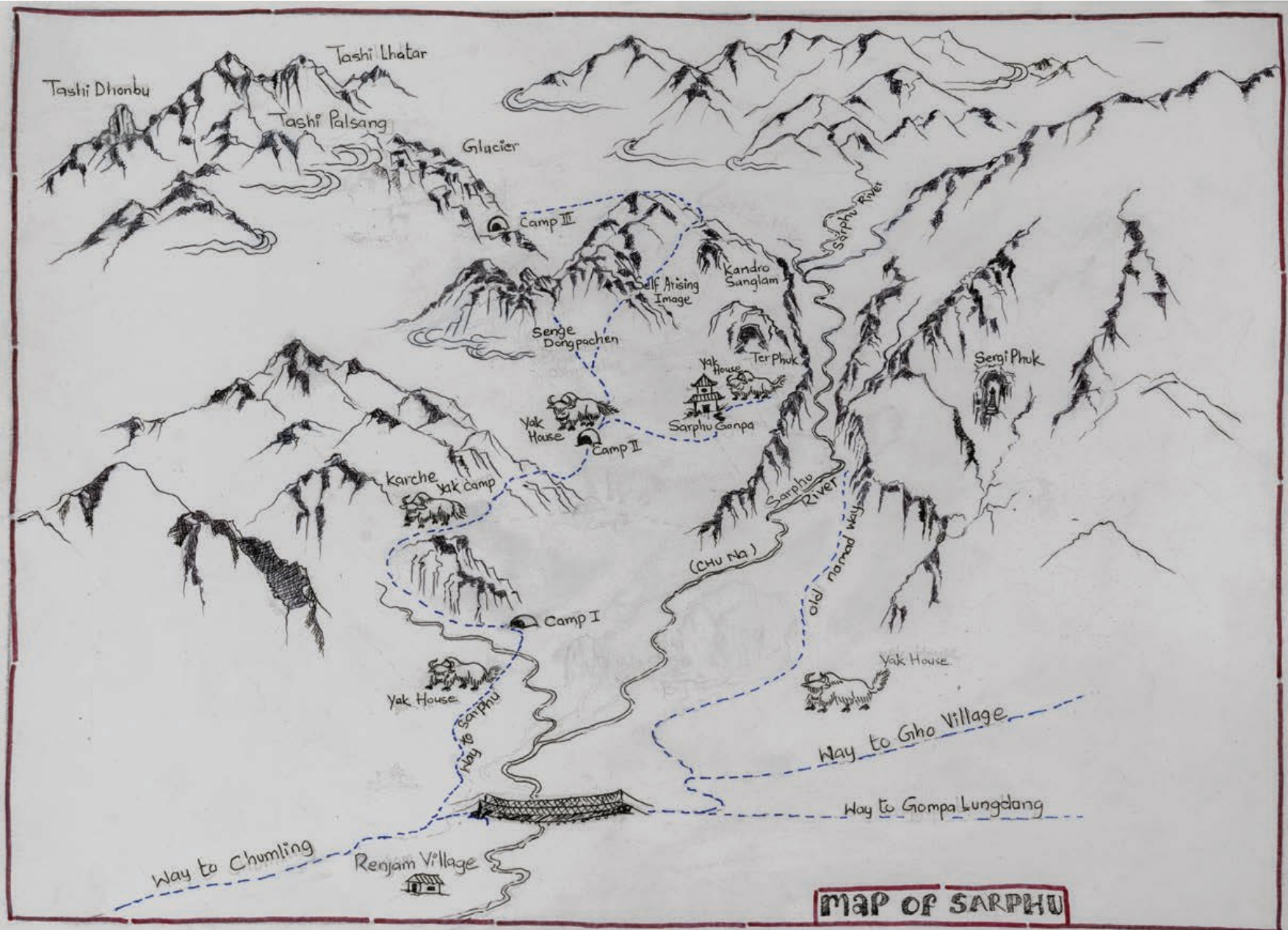

Map of Sarphu Valley, Tsum, based on Marshall’s expedition. Some of the place names were shared by nomad Tsewang Norbu, and others come from the neyig. Courtesy of Sangay Phuntsok

There are many memorable figures you meet throughout the book. Are there any whose wisdom or presence stays with you the most in your day to day life back in Canada?

So many. I feel like I live with these wonderful people every day in my memories and I’m in regular contact with many of them still. Conrad Little Leaf, a Piikani Elder, is often in my thoughts. He gave me a Blackfoot/Soki-tapi name that means “Walking Above.” He really knows my heart—how much I love being up high in the mountains, and how I’m looking for the deeper, higher stories. I continue to work closely with Tanzin, my friend and guide from Tsum, to bring trekkers to Nepal and show them Happy Valley firsthand through my company Karuna Mountain Adventures, and we also run a charity up there called The Compassion Project that provides free health care and kindergarten to the villagers.

Students, parents, Tanzin (left) and Ward Chief Lama Pasang (center, in red) gathering for a school photo in Lamagaun, Tsum. Provided photo

Tibetan Buddhist nun Ani Pema and I made it to the heart of the Nepal Happy Valley together, and she is my sister. My heart was broken when she passed away last winter. She was my age, 42. It was extremely special and timely that we had that adventure together before she died. I still feel her in the land.

Ani Pema and Jane Marshall in Tsum. Provided photo

Lastly, Drakar Rinpoche, the 17th reincarnation of his lineage. He’s very special to me.

You note that “the earth has the capacity to make us right again.” How did this become clear to you across your travels?

It’s so true, isn’t it? There is less anxiety and neurosis when we live more closely with the earth. There is less suffering when we have a community or a village that respects the land and lives with compassion. We are made of earth, we come from it, we return from it, we ARE it. It’s when we forget that connection that we suffer.

Team Sarphu: Ani Pema, Marshall, Tenzin, Rinzin and Tanzin at Tashi Palsang. Provided photo

Is there anything else you would like to note to Kinute’s readers about this book?

I found that it was easier to fly to Nepal to access Indigenous wisdom than it was to make connections in Canada. That speaks to the atrocities that occurred here and in North America. It would be amazing if, and I’m writing to non-Indigenous readers with this comment, we could make an effort to personally connect with the Indigenous peoples where we live. To sit, spend time, and listen. In his book "The Wayfinders," world renowned Anthropologist Wade Davis writes about the incredible technologies many Indigenous cultures have honed over the ages, and he asks us to learn from them so that we can develop methods to understand and save the Earth. Let’s do it! Maybe, if we ask and listen, we can find new ways of conservation and relationship with the land all across Turtle Island. Wouldn’t that be amazing?

Marshall on Nāāpi’s spine. Provided photo