In his debut book The Dawn Patrol Diaries: Fly-Fishing Journeys under the Korean DMZ, James Card takes readers on a unique angling adventure in South Korea, blending a love of nature with a deep exploration of the country’s hidden landscapes and complex environmental issues.

Released Sept. 1, this memoir delves into Card's experiences as a self-taught fly fisherman, his encounters with South Korea’s native and invasive fish species, and his reflections on the country's unregulated waters and fragile ecosystems.

Kinute had the chance to speak with Card about his journey from the trout streams of Wisconsin to the rivers winding beneath the Korean DMZ, and his hope to inspire a greater appreciation for Korea’s waterways and the natural world at large.

When and where did you learn to fly fish?

I grew up in Wisconsin’s Driftless Area, that topographical pocket of steep bluffs and river valleys that covers southwestern Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota, northeastern Iowa, and a bit of Illinois over by Galena. Winding through these coulees are thousands of trout streams—so I had that going for me.

I grew up fishing with my father using various lures and live baits and catching all kinds of fish. I’m a self-taught fly fisherman. I had no mentors. I learned from books and lots of frustrating trial and error. I figured it out more as a college student and then got serious about mastering it as an adult.

The author studied saltwater fly-fishing techniques for bonefish to catch these freshwater barbels in South Korea. (Photo: James Card)

Why did you move to South Korea and what inspired you to start fly-fishing there?

I moved to South Korea as a way to see the world yet have the ability to make payments on my student loans. At the time, teaching ESL (English as a Second Language) was a semi-lucrative gig for a young college graduate with a vagabond itch.

I brought along a two-piece spinning rod and a small tackle pack. I had no idea what kind of fish lived on the Korean peninsula. At first, I lived on an island along the southern coast so I took up spearfishing. Later when I moved to the mainland, I discovered populations of non-native invasive largemouth bass and bluegill. They were imported decades ago in a harebrained fish farming scheme and now they are all over the country in a food chain they don’t belong in.

As I was catching these familiar species of fish, I also started hooking into some of the fish native to Korea. For some of these species, the best way to catch them was through fly fishing.

South Korea holds the world's southernmost population of lenok, also known as Manchurian trout. (Photo: James Card)

What inspired you to write this book?

Part of it was capturing knowledge that could be lost. I spent years getting to know the various species of native Korean fish and figuring out how to locate and catch them. Although there are plenty of Korean anglers that are familiar with these fish, there was hardly any information about them in the English language. I was always taking field notes about what I learned, not just about fish but also about all kinds of interesting flora and fauna.

A rare sandy beach on a trout stream in South Korea. Perfect for a campsite. Most open areas near mountain streams are gravel bars. (Photo: James Card)

What is the significance of the title?

I love to fish in the early morning. I love to drive to my angling destination in darkness with a mug of coffee at my side. It’s the best time of the day.

In South Korea, there are no fishing licenses or any developed angling regulations. Therefore it can be a poacher’s free-for-all, an angling version of the tragedy of the commons. So when I rolled up to a beloved fishing spot, I was always on patrol for evidence of other anglers. I found gill nets stretched across trout streams and cylindrical fish traps with inverted entrance cones—which left unattended are perpetual fish-killing devices.

Also, another thing to be on the lookout for was the march of the construction cartel. I would discover a small lovely creek and return three months later to find an excavator in the river bed and a cement truck pouring a pointless low-head dam. The more I explored the more unnatural channelized streams I found. Some of these streams still held trout but they were unhealthy ecosystems.

This in turn pushed me further and further into the backcountry. I not only had to get off the beaten path, I had to find streams in areas where heavy machinery could not access.

Card studies a pool with a client while fishing a trout stream in South Korea. (Photo: James Card)

Why do you think no one else has discovered fly-fishing the way you have in South Korea?

There are very few Korean fly anglers compared to South Korea's 50 million population. I was able to look upon these waters with an outsider’s perspective and ask why so many of these streams are channelized with concrete. Whereas a Korean angler grew up fishing on river banks covered with cement—they never knew anything different. Also many of the river conservation and restoration concepts (such as those promoted by Trout Unlimited) have not made it across the Pacific. In the U.S., dam removal is in the public consciousness, in Asia they keep finding excuses to build another one as a make-work project to raid the public treasury. The fish, or course, do not have a say in the matter.

There are also two types of traditional versions of Korean fly-fishing. One method is to use a very long tenkara-style rod and make spey-styled casts to swing wet flies for migrating shad. Another is a gyeongi rod which is a small rod less than three feet long and topped with a helix ladder with a line wrapped around it. The line is let out into the stream by spinning the helix.

Card's cocker spaniel often went along on fly-fishing trips. South Korea is rich with ring-neck pheasants and the dog flushed hundreds of them every year. (Photo: James Card)

What challenges did you face as the country's only fly-fishing guide?

When I started guiding, my biggest challenge was logistics, of getting clients from a major city to a smaller provincial city that would be a jumping off point to the area where we would be fishing. I doubled as a travel consultant and provided bus and train schedules and accommodation recommendations.

I also provided lunch so I had to round up those ingredients. What to serve? I eventually discovered that egg-salad sandwiches and deep-fried chicken served cold (“picnic chicken”) were the most popular streamside foods. I also rounded up various fruits from the farmers’ markets when they were in season. Everyone loved slices of Asian pears and persimmons.

The mayflies, caddisflies and stoneflies of the Korean peninsula are comparable to those in other parts of the world. It's only a matter of matching an approximate size and pattern to mimic what is happening on (or under) the water. (Photo: James Card)

How would you compare fly-fishing in South Korea to other parts of the world?

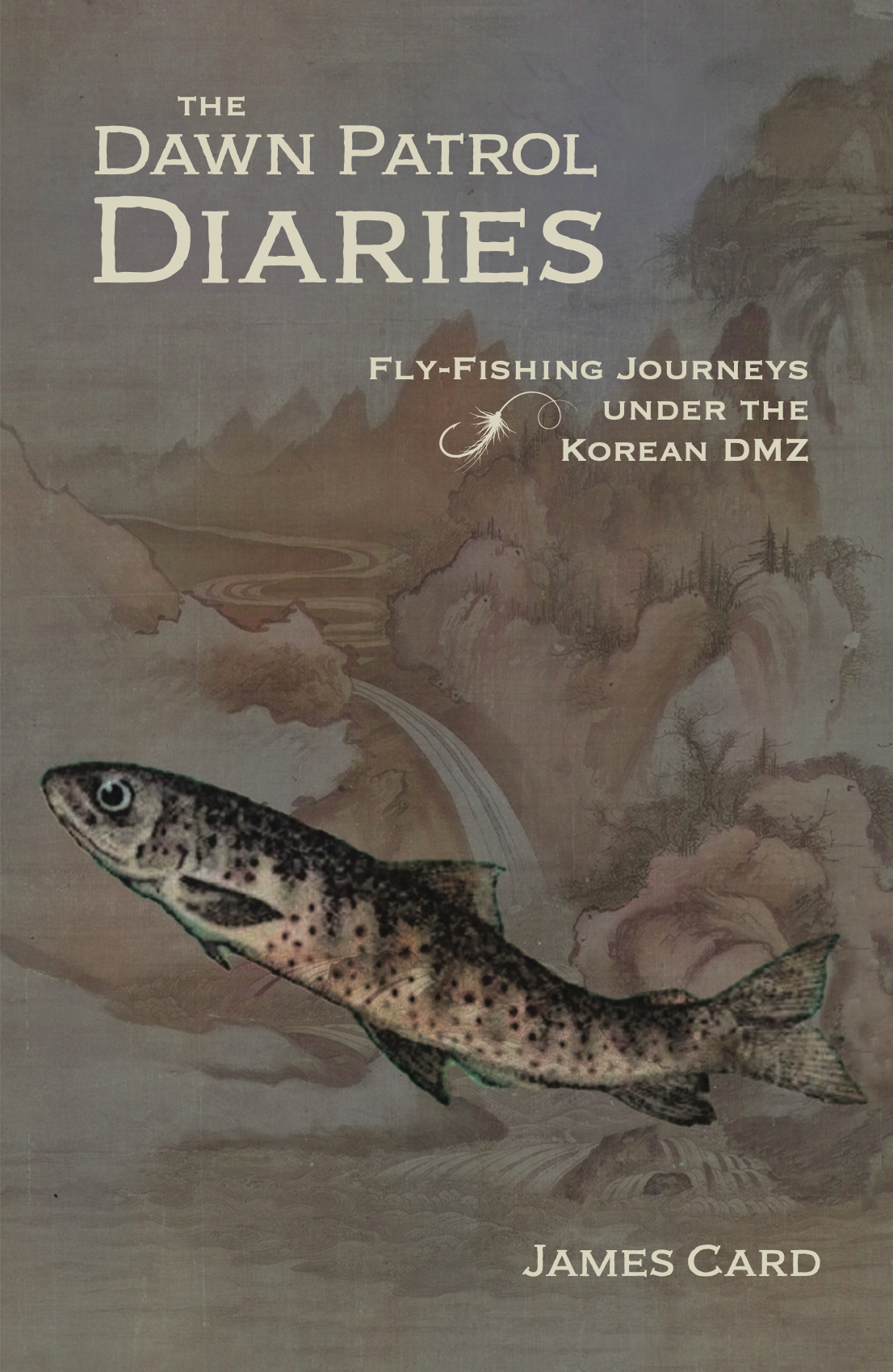

On the cover of my book, the background is a scene from a true-view landscape painting (jingyeong sansuhwa), a style that evokes what I often experienced when afield: a forbidding mountain range with jagged peaks and a narrow valley with a river tumbling down. There are scraggly pine trees growing off cliffs and tucked away somewhere is a Buddhist temple or a Confucian seowon (an academy). It’s my favorite kind of Korean artwork. On many fishing trips I felt like I was walking into one of those paintings.

Around 70% of South Korea is mountainous. There are some spring creeks that flow from caves and there are freestone streams that tumble down steep mountainsides. (Photo: James Card)

Tell us about the DMZ land and its history.

The DMZ has layers that stretch across the Korean peninsula. It’s not as if a North Korean soldier and a South Korean soldier are facing off nose-to-nose with a chain-link fence between them. There is a civilian-control area where farmers are let into to tend to crops. Then there are restricted military-only zones and then another mile or so back you can finally get a glimpse of North Korea in the far distance. I was able to do that (with army escorts) while reporting about a rare alpine wetland that exists in the DMZ. It was a quiet and peaceful place.

A land mine flag along the Korean DMZ. (Photo: James Card)

It is also an accidental nature preserve to an extent but it’s not an untouched paradise. The military has a heavy footprint and in years past they have burned brush and sprayed herbicides to keep the foliage in check so they can better observe infiltrators. However there are reports that wildlife is flourishing in a mostly unmolested environment. There are wild boars, gorals (a kind of mountain goat), water deer and I believe Korean leopards still exist up there. There are some that think the DMZ might hold tigers but that’s a long shot.

There is also a ghost town element to the place. There are buildings, railroads, pagodas and ruins left untouched since the Korean War. It’s frozen in time. The only people that get to see that are soldiers that happen to be assigned to patrol those areas.

A war monument in the Jiri Mountains. After the Korean War ended, partisan guerillas hid out in the mountain range and continued operations. (Photo: James Card)

What are the dangers facing South Korean villages? How will this impact the natural landscapes you’ve explored?

South Korea has one of the lowest birth rates in the world. This is most evident and disturbing in rural areas. Young people flock to the big cities and the elderly are left behind in the mountain villages. In many places it’s like an open-air old folk’s home. They were often shocked and delighted to see a Westerner (with a fishing rod, of all things) stroll into their village. I loved to chat with these old timers and they were always generous with offering a snack or some rice wine.

Once they are gone, who will maintain their rural traditions and who will populate these wonderful landscapes? South Korean agriculture has always been small-scale and not very lucrative. I suppose it’s the same question facing many people around the world: how does one live in a beautiful rural area that doesn’t have much going for it economy-wise and be able to make a living—or raise a family? It’s an old and universal question.

Although rural areas in South Korea are depopulated, events like bullfights and small festivals temporarily inject some vitality in many super-aging villages. (Photo: James Card)

What's one thing you hope readers take away from the book?

Take a map and find the emptiest spot on the map. A place with the fewest roads and fewest towns. In many of these places I found the best fishing spots but you find other wonderful things, too, such as older architecture that is preserved, more untouched natural areas, friendlier people, less franchised retail operations, and some odd regional things.

If you are lucky some of these places will have a lost-in-time feel to them. You have to experience it before it’s gone.

The Korean piscivorous chub, a predator cyprinid, loves to attack streamers as minnows make up most of their diet. (Photo: James Card)

Any advice for someone traveling to South Korea for the first time?

Learn hangul, the Korean alphabet. That sounds insane for a first-time trip but it’s easy to achieve. It’s a brilliant phonetic alphabet and the script is very different but it’s as easy as learning the ABCs. There are plenty of study materials online and if one is disciplined enough, you should be able to figure out the basics in an afternoon. After that, it’s a matter of memorization and repetition.Make some flash cards.

So with some pre-trip effort, you could be reading and sounding out street signs as soon as you get off the plane. Or reading a menu or finding your destination city on a bus schedule. You might read like a first grader and you will not know what much of it means but at least you can sound out words and have some level of basic communication. That is extremely enriching and empowering for a travel experience.

Where is home to you now, and what's your next adventure?

I live along the Tomorrow-Waupaca River in central Wisconsin. The next adventure is coming up this winter as I’m writing a book about the world of ice fishing. It will delve into the culture, history and evolution of this winter sport. I will be spending a lot of time on the hardwater talking to lots of people and trying to capture the magic and appeal of catching fish through a hole cut into a vast slab of ice.