Deepwater diver Tim Shivers looks forward to every underwater exploration, but in recent years there’s one mission and species that captures his full attention.

“I love lionfish. It’s my favorite thing to dive for,” said Shivers, captain of DeepWater Mafia diving group.

Shivers is not alone in his focus on lionfish and the attention on them isn’t coming from their colorful, venomous spines that make them a popular centerpiece for home aquariums. Instead, the spotlight is on lionfish because they are enemy number one for marine biologists along the eastern seaboard, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico.

An aquarium release in the mid-1980s is believed to be responsible for the outbreak of invasive lionfish that is now nearly impossible to control. They are rapidly taking over coastal reefs in such staggering numbers that it is wiping out important segments of biodiversity. Lionfish were first spotted offshore in Southeast Florida before spreading throughout the eastern seaboard, Bahamas, Caribbean, South America and the Gulf of Mexico, the last and most prevalent location of their invasion. Destin-Fort Walton Beach in Florida is facing the brunt of it.

“We were the last place that lionfish made it, but they exist in higher densities here than anywhere else in their invasive range,” said marine biologist Alex Fogg, coastal resource manager for Destin-Fort Walton Beach. “They are on just about every reef you go to from 6 feet of water to 1,000 feet of water.”

One of the most compelling insights into the scope of the lionfish invasion comes from a 2008 study (Per Albins and Hixon) looking at the species assemblage on coral reefs in the Bahamas and Florida Keys from the 1980s onward. The findings show that lionfish decreased the populations of native species on some reefs by over 90%. While the study was conducted in the Bahamas and not the Gulf of Mexico, its findings reveal the destruction potential and pressure that lionfish put on reefs and native species.

The silver lining? Despite being venomous and its relentless reputation, lionfish are safe to eat which could be the one chance at controlling them. Destin-Fort Walton Beach in Florida is not just the hardest hit location of invasive lionfish, but one of the most aggressive and proactive when it comes to keeping the pressure on to manage them.

Implementing a unique and sustainable win-win solution to control lionfish populations, Destin-Fort Walton Beach is putting marine biologists, skilled divers, local restaurants, chefs and consumers on the front lines against this invasive species. It is a collective effort to keep the pressure on so that native species have a chance to survive.

Invasive lionfish on an innovative lionfish trap. Photo by Alex Fogg

The lionfish invasion

The scale of the lionfish invasion is best explained with simple facts: the average size female lionfish lays on average 27,000 eggs every 2.5 days and can start reproducing earlier than other species; they can consume 20 fish in a half hour and eat prey 2/3 their size; their menu is large enabling them to consume more than 90 different species of fish and invertebrate and they are protected by 18 venomous spines, their most protective and recognizable physical feature.

With these factors at play, native species hardly have a chance at taking care of the problem themselves.

“Lionfish reproduction is comparable to native species reproduction, but their eggs have a higher success rate to make it to adulthood. They also reproduce within the first 6 months of life compared to a grouper or snapper where it is years. There are fish that do eat lionfish like groupers, snappers, eels and sharks but not enough to keep them under control and their venomous spines make them too spicy for most potential predators,” said Fogg.

Fogg started researching lionfish in 2012 collecting samples from all over the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida Keys. He helped initiate lionfish tournaments like the Emerald Coast Open in Destin in 2019 that resulted in more than 15,000 samples enabling him to observe the life history of lionfish by looking at factors like age, growth, reproduction, diet and parasites that can impact their existence.

Fogg uncovered some interesting findings in his research including potential vulnerabilities of this once-considered untouchable species.

“The metrics have changed since the first studies early in the invasion,” said Fogg. “In 2017 an ulcerative skin condition began presenting on lionfish throughout their invaded range and shortly after there was a huge decline of 77 to 79% on artificial reefs that you used to be able to go to and find 300 lionfish. After the decline, it was difficult to find a site with more than 30 fish.”

While there is no doubt that lionfish are destructive to reefs and native species, there are the other factors that Fogg says cannot be ruled out like oil spills and climate change that also have an impact on marine life. Lionfish are just another stressor in that system.

Alex Fogg holding two collected lionfish. Photo by Alex Fogg

Removing lionfish one-by-one

The effort to target the invasive lionfish is an exhausting, and sometimes painful manual effort led by experienced divers who must spear them and remove them one by one from coral reefs.

“Lionfish are here to stay,” said Fogg. “We’re never going to get rid of them. They survive out to 1,000 feet of water and the only way to get them is diving. With how fast they reproduce, how quickly they mature and how old they get it makes it very difficult, but you can keep them under control on a local level.”

That’s why incentivizing divers through tournaments like the Emerald Coast Open is important. The tournament that specifically targets lionfish is held each May in Destin, Florida and divers come from all over the United States for a chance to win top prizes with money raised from sponsors.

“It’s a full-blown fishing tournament so the team that brings in the most lionfish wins $10,000. The biggest lionfish is $5,000, and the smallest is $5,000 to incentivize every single lionfish to come out of the water,” said Fogg.

These efforts work.

In 2022 the Emerald Coast Open netted over 15,000 lionfish in a 2-day period with 145 divers participating. They are hoping for over 200 participants in 2023. A pre-tournament period from February through mid-May enables divers to collect lionfish and sell them to local restaurants, who then participate in a restaurant week to encourage local consumers to come out and try something new and exotic on the menu.

The dive team DeepWater Mafia, headed by Captain Tim Shivers, won the tournament in 2022 with four divers bringing in 1,746 lionfish. This will be the eighth year the team has traveled from Ocean Springs, Mississippi to participate.

“I love being a keen part in keeping our waters something that my kids and grandkids can fish in forever and keeping lionfish at bay is one of those efforts because they consume the smaller reef fish,” said Shivers. “I don’t know that we’ll ever completely rid our ocean of lionfish but if we can keep them at bay and sustainable then that’s our goal now.”

Tournaments like these that remove tens of thousands of lionfish at a time give the local ecosystems a fighting chance because it gives the native species a break. Long-term success can only come by keeping that pressure on by keeping the lionfish populations suppressed.

Divers collecting lionfish from reefs. Photo by Alex Fogg

While sustainable management of lionfish is the goal and there are financial incentives to make it happen, those aren’t the only reasons that divers like Shivers do it.

“It’s so much fun,” said Shivers. “First, you know you’re doing good for the environment and second, it’s just fun. When I tasted lionfish for the first time, I realized this is my literal number one favorite fish to eat on the planet and restaurants are now seeing lionfish as a viable long-term menu item.”

Harvesting lionfish requires great skill and experience with the precision needed to collect them one at a time. Shivers uses what is known as pole spear with a band that is manually pulled back and released with a paralyzer tip inserted into the fish. The collected lionfish are then put into a cylindrical-shaped zookeeper to protect divers from the venomous spines. While Shivers and his team of divers have perfected lionfish collection, he admits there is a steep learning curve.

“It was trial by fire,” said Shivers, who can now laugh about the learning process. “I got stabbed several times and spent a couple sleepless nights in the hospital getting treatment.”

In one instance Shivers’ foot slipped off the deck of a boat into a fish box causing him to get stabbed seven times on the foot. Another time, a lionfish spine stabbed Shivers under his wedding ring. Both instances required hospitalization and medication.

While humans often take the rap for harming the environment, harvesting lionfish is one area where humans are the only chance for controlling this invasive species.

“Lionfish is one fish that you want to overharvest,” said Fogg. “We will probably never get to that point but it’s a sustainable option that we will have forever. While there are closed seasons for certain species, this is a fish that you can harvest as many as you want. Lionfish are completely safe, they’re tasty and extremely healthy to eat.”

Ongoing lionfish tournaments and regular research on their populations along with the commitment from divers is only part of the solution puzzle for controlling the problem. The final and essential pieces of this sustainable solution are the restaurants willing to buy lionfish and put them on the menu and the consumers willing to try them as an alternative seafood dish.

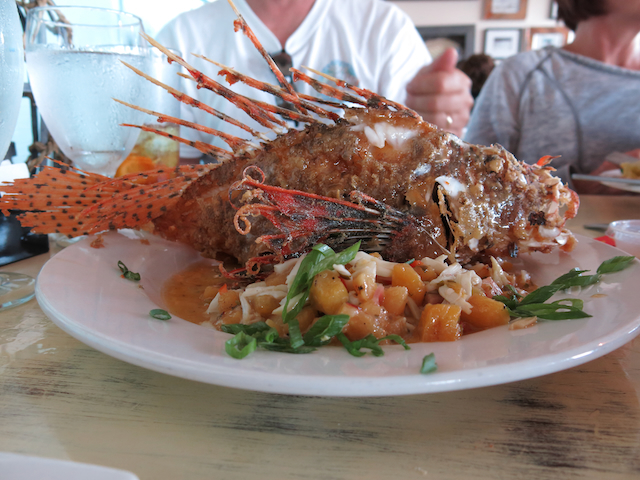

Lionfish prepared fried as an entrée at a Destin-Fort Walton Beach restaurant. Photo by Alex Fogg

An exotic culinary experience

Lionfish purchased by local restaurants like Dewey Destin’s Harborside Restaurant in Destin is an opportunity to offer an exotic menu item and educate the public about this species and its culinary possibilities.

“Anyone can get grouper. Lionfish is different. The meat is so delicate that it can easily be a substitute for crab meat,” said Chef Jim Shirah of Dewey Destin’s Harborside Restaurant.

Lionfish meat is so versatile with a mild taste that can be prepared in many ways from sashimi and grilled to fried. Then, there’s the health benefits.

“The flesh is white, they’re high in Omega-3 fatty acids, more than salmon so it is an extremely healthy option,” said Fogg. “If you can drive those things home to the public through education then it makes for an awesome seafood option.”

The biggest inhibitor to people trying lionfish is the misconception that lionfish are not safe to eat because they have venomous spines.

“People are scared because they don’t understand the difference between venomous and poisonous,” said Shirah.

Lionfish are not like puffer fish that must be cleaned and prepared in a specific way or consumers can get sick. Lionfish have a venom that is injected by the spines but the meat itself is completely safe to eat no matter how it is filleted and prepared.

Chef Jim Shirah showcasing a bronzed preparation of lionfish as a dinner entrée. Photo by Anietra Hamper

Chef Shirah cuts off the tips of the venomous spines, then filets the fish and gets creative whenever he has it available to serve. He likes to showcase the variety of possibilities with lionfish meat with snacks like lionfish cakes, frying the entire fish, quick bites of fried fish or full entrees with a bronzing preparation.

Admittedly, Chef Shirah is as fascinated by what he often finds in the stomachs of lionfish while prepping them as with the creations he gets to make.

“I’ve found lobster, other lionfish and all kinds of things in their stomachs,” said Shirah in a giggle much the way a scientist might describe a new find. The stomach contents exemplify the enormous appetite and consuming potential of these fish that have only been recorded at a maximum length of just under 20-inches.

Though educating the public about consuming lionfish takes some effort, once people try it, the species often becomes a new favorite. The next step in the process is balancing the supply with the demand. Since collecting lionfish is so labor-intensive, divers are not going out every day to collect them, meaning the species is unlikely to be a permanent fixture on the menu. Restaurants like Dewey Destin’s are ready and willing to step up when and if the supply side expands.

“We can’t keep it on the menu when we get it,” said Shirah. “We only get it a few times a year, maybe 40-pounds a year, and when we do have lionfish, we are sold out by lunchtime, so any diver who is willing to do it and sell to restaurants has a market.”

Dewey Destin’s Harborside Restaurant is one of eight local restaurants participating in the Emerald Coast Open Lionfish Restaurant Week supporting the efforts to incentivize divers to harvest the lionfish and educate consumers to keep the sustainable cycle viable.

Lionfish on Florida’s coral reefs. Photo by Mark Miller

The ripple effects

Lionfish are here to stay as the prospect of getting rid of them is not attainable. The only option is to manage their populations to protect the native species through the process.

“If we can sustain a commercial market and continue to educate consumers to ask for lionfish at restaurants, and if we can raise the price enough that the divers are incentivized to go out there and collect them and sell them then we can maintain a sustained harvest. Humans have a good ability to harvest things, so we can put a serious hurting on lionfish if we can figure out a way to get them efficiently,” said Fogg.

The cycle of the solution is clear, but it will continue to require all hands on deck going forward which is something that looks promising according to those on the front lines who are taking the initiative to make it happen.