Nearly 30 years ago, on the site of a shuttered sanitarium, an environmental education center in the name and spirit of Aldo Leopold was founded.

Tucked away in the city of Monona, Wisconsin—snuggly situated beside the state’s capital, Madison—the humble beginnings of the Aldo Leopold Nature Center (ALNC) were born in a converted greenhouse on a 20-acre oasis within the city.

When the center was founded in 1994, the tract, which abuts other preserved lands, already boasted a park-like setting from its time as a healing sanctuary.

The founders, who included Madison philanthropist Terry Kelly and Leopold’s eldest daughter Nina Leopold Bradley, established the center with the guiding principle to “Teach the student to see the land, understand what he sees, and enjoy what he understands,” as Aldo Leopold wrote.

The Aldo Leopold Nature Center in snow. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

Throughout its nearly three decades in operation, the center has evolved in many ways. While their first year realized 4,000 visitors, that number has grown to over 80,000 annually. The building infrastructure has graduated from that simple converted greenhouse to a full-fledged nature center built in 1997, followed by an 11,000-square-foot addition in later years.

The center now hosts many programs including a nature preschool, after-school programs, field trips, summer camps and special events.

They have also begun taking their offerings on the road to area community centers in order to reach a broader audience, as well as providing transportation to the center for select after-school programs—recognizing that, for some, transportation to the center can be a barrier to enjoying this resource and connecting with nature itself.

These efforts are being made in an attempt to leave no child behind in the pursuit of ALNC’s mission to “Engage and educate current and future generations, empowering them to protect, respect, and enjoy the natural world.”

Bullfrog observation. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

Leopold’s life and legacy

Aldo Leopold was born and raised in Burlington, Iowa. He spent his boyhood exploring and observing along the banks and amidst the bluffs of the Mississippi River. These formative experiences arguably influenced Leopold for the rest of his life.

As a young man, he earned a degree in forestry from Yale University.

Following his time at Yale, Leopold joined the U.S. Forest Service. He served in the Arizona and New Mexico Territories, where the budding concepts for his seminal land ethic began to take shape.

Leopold came to see the Earth as a living organism, a community—of which humans are a part, not conquerors of. This blossomed into the concept that we cannot care for people without caring for the land, indeed, that it is our moral imperative to do so.

An opportunity to transfer to the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin, brought Leopold back to the upper-Midwest, where he spent his life and career in service to nature and its protection.

Leopold is often cited as the father of wildlife ecology. As ALNC states, “Leopold’s cornerstone book, Game Management (1933), defined the fundamental skills and techniques for managing and restoring wildlife populations.”

Going on to state that “This landmark work created a new science that intertwined forestry, agriculture, biology, zoology, ecology, education and communication.”

On the heels of the publication of Game Management, came the creation of a new department at the University of Wisconsin—The Department of Game Management—with Leopold serving as its first chair.

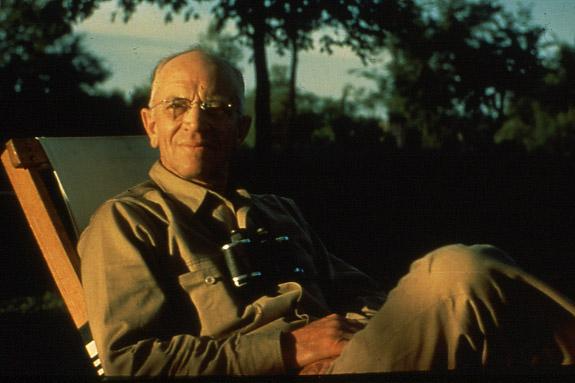

Aldo Leopold. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

Leopold taught at the University of Wisconsin from 1933 until his death, in 1948.

Not long after Leopold began his work with the university, he and his family purchased an overworked piece of land along the Wisconsin River, outside of Baraboo, Wisconsin. Whenever time afforded, the family would travel the shy 50 miles to the beloved Shack—as the chicken coop turned cabin, that sat upon the site was affectionately known.

The land served as a living laboratory where Leopold could experiment, putting his theories about land restoration into practice. It was also here, that many of his ruminations and observations for the essays that would become his most well-known work, A Sand County Almanac, solidified.

Leopold died shortly after he received the news that A Sand County Almanac would be published. While he did not live to see the rippling effects that his most famous text would have, they have been felt and seen throughout the conservation community for the past 75 years.

A new generation

Leopold’s legacy is alive and well at ALNC, where an ever-increasing number of students have been shepherded into the stewardship fold over the years.

This spirit is both, woven subtly into the fabric of the center’s ethos and painted in bolder strokes, depending on the program that students participate in.

“The philosophy of having children be in nature-based spaces…naturally builds an appreciation for the outdoors and then there are a lot of teachings around biodiversity that are embedded in what our environmental educators are doing,” said Melissa Salisbury, program impact and inclusion manger for ALNC.

Members of the Tadpoles program examine caterpillars. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

The nature preschool at the center is a particularly immersive experience, with students engaging in outdoor activities year-round in Wisconsin’s variable weather conditions. All students are equipped with heavy-duty snowsuits and rainsuits, and the center is overflowing with the extra gear that is inevitably needed when children are getting up close and personal with the natural world.

While the center itself sits upon 20 acres, the total footprint of protected land that it rests within, is 100 acres. This corridor proves to be a safe haven for wildlife within an urban environment.

Foxes, coyotes, sandhill cranes, owls, frogs, turkeys, and many other species can be found on site amidst the woods, prairie, or pond, providing countless opportunities for students and visitors to observe local fauna.

While the animals will not submit to lesson plans, lessons are fluidly guided by wildlife observations. “We're always observing everything that we see with students. We have learned that that feels like a better approach,” said Virginia Wiggen, ALNC’s Education Director.

Salisbury underscored this point, by adding, “Teaching phenology would encapsulate a lot of what we do, which is in the spirit of Aldo Leopold…taking note of everything that's changing seasonally is definitely a theme that weaves through all of our programs.”

More overt stewardship efforts have been braided into an after-school program, where older students participate in a formal stewardship day each week, working to remove invasive species, wash windows, and other activities that directly care for the land and the center itself.

After school program participants cut buckthorn. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

Because the center hosts programs for children from ages two through 14, opportunities for the older set to assist the younger have arisen. Older students are currently designing a boot drying system for the preschoolers, who cannot be bothered with the tedium of keeping dry through the course of their daily adventures and explorations.

Additionally, past summer programs have hosted junior naturalists—a designation for older students who are phasing out of the center’s programming, but who are still looking to engage. Junior naturalists help to teach and guide younger students, while earning valuable work experience and accruing volunteer hours.

In this environment, the educators have witnessed the students thriving. While there are innate challenges to such immersion in the natural world—variable weather, tests of strength or stamina in physical tasks, navigating new experiences—there is also a richness that would otherwise go unrealized.

These benefits include the opportunity to move their bodies and be much more physically active than in traditional educational environments, a focus on observation to attune students to their environment and themselves, and a natural nurturing of curiosity through learning about these observations in real time.

Peeking out of a fort. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

The positive impact of these experiences has been felt through the joy that radiates from the children, the observable confidence that has built in the students, and the many kind words of praise that the center and staff have received over the years.

One notable highlight was a few years ago when the center received an intern application from a former student who had vivid memories of coming to ALNC in their youth—citing those foundational experiences as a key factor in the choice to pursue a career as an outdoor educator.

Ongoing evolution

While Leopold’s legacy and land ethic are the pillars that ALNC is founded upon, the center has been striving to expand the reach of their work and mission in recent years.

This has included efforts to improve access, as well as fostering diversity, equity and inclusion in acknowledgement that nature is for everyone.

A member of ALNC’s Cottontail group exploring the mud. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

“It’s really essential to give everybody this opportunity to love the land and learn how to be thoughtful stewards of the environment,” Salisbury said. “The more people who can develop that love and appreciation of nature and the outdoors, then the better we are able to meet larger global goals of fighting climate change.”

To foster expanded participation ALNC has now chosen to make all their special events free, moved their enrollment to a lottery system, and has undertaken the process of making many of their programs eligible for a local subsidized child care initiative.

In evaluating where they want to go in the future, ALNC is also looking to the past to honor those who have stewarded the land before them—indeed before Leopold or any person of European descent.

The center acknowledges that the site upon which they sit was historically Ho-Chunk land.

While Leopold’s land ethic is rightfully celebrated, it was arguably The First Nations who had truly embodied this harmonious relationship with nature for generations, before it gained more modern popularity.

Of the center’s planning for the future, Cara Erickson, ALNC’s marketing and communications manager said, “We are thinking beyond Leopold. We recognize that as the Aldo Leopold Nature Center, we are named after a great conservationist … who had great works and great teachings, but we recognize that those teachings weren't necessarily new, that there were people on this earth before him who … thought about nature and the environment in the same way.”

It is through this self-examination and commitment to an ongoing evolution that ALNC will continue to ensure and build upon their success in engaging, educating and empowering current and future generations in an ever-expanding way.

Replica of Leopold’s shack at ALNC. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

In a replica of the Leopold Shack that sits upon the ALNC site, a copy of "A Sand County Almanac" has always greeted guests upon entry to remind visitors of the great conservationist whose life’s work was in service to the land.

That book no longer sits alone in the quiet Shack, it now keeps company with Braiding Sweetgrass and other works that acknowledge the diverse voices and faces in the conservation space that have not yet been placed on a pedestal quite as high as Leopold’s—though they contain equal wisdom and are in kind with his legacy.

As Erickson said, “Nature is everywhere, and it is for everyone. We want to do the right thing in the world and that is to be as accessible as possible to our diverse community.”

While the center recognizes that this is an area of growth for them, results are beginning to be seen. Students that wouldn’t have access to after-school programs are now regulars at the center due the newly-purchased 15-passenger van that shuttles attendees at a time of day when many parents simply can’t.

ALNC’s van shuttling program participants. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center

Children for whom engaging with the natural world is foreign or even scary are gaining confidence and finding their place amongst what is rightfully theirs to enjoy.

Like the anecdote Salisbury recounted of one tentative summer camper, who when faced with the prospect of entering the shadowy woods, froze.

Initially he expressed his fears that woods are bad and that scary things happen there. His mentors did not push, but rather read his cues, provided safe experiences and interactions, and allowed his peers to model safe adventuring within the environment.

By the end of his time at camp, that little explorer was empowered to rove in every area regardless of sunshine or shade, wetland or woodland—emboldened by the positivity and possibility of these new exploits.

As Salisbury says, “It speaks to the impact that we can have when we give kids these experiences.”

An impact that will continue to be felt as the torch that burns with a passion for the protection of the natural world is passed from generation to generation.

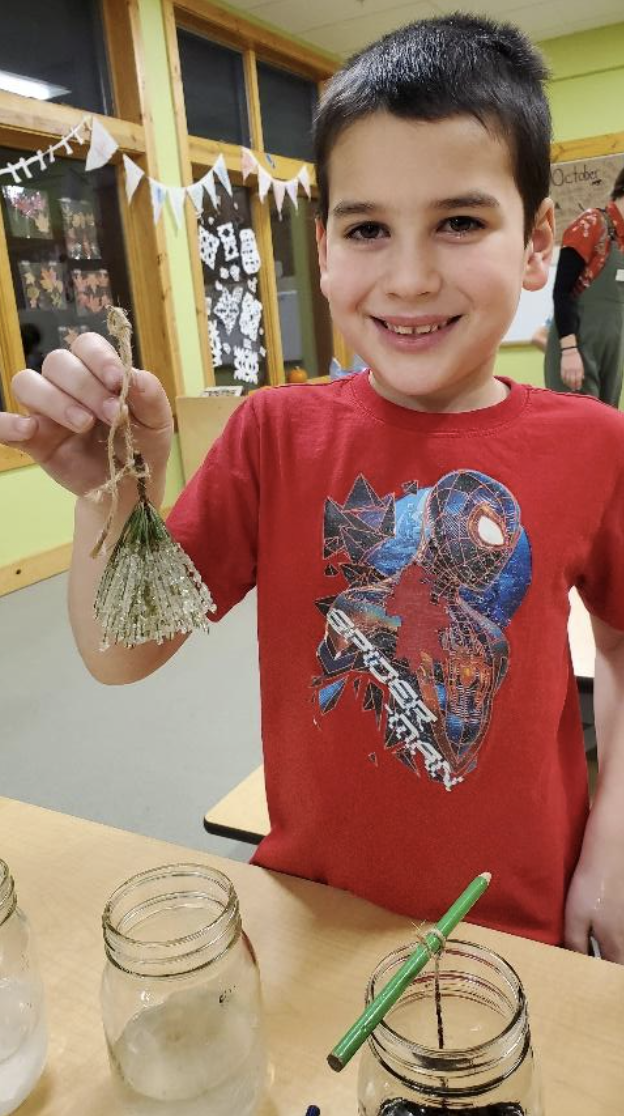

Making crystals. Courtesy of Aldo Leopold Nature Center