Barbara Ernst Prey has been drawn to art her entire life — she has no intentions of brushing it aside.

“As an artist I am a creator, observer, interpreter distilling my subject and pulling from a lifetime of learning,” Prey told Kinute.

She is primarily known for her watercolor paintings of natural landscapes. Over a career now spanning more than four decades, she has created hundreds of pieces, and had them displayed alongside other master artists at prominent museums and galleries.

“Waterlilies,” painted in 2012, illustrates Prey’s precise use of color in depicting natural scenes. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

Prey’s work has been featured at MASS MoCA (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art), The Brooklyn Museum, The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., The White House, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Kennedy Space Center, Williams College, Williams College Museum of Art, Hood Museum, Dartmouth College, The New-York Historical Society Museum, The George W. Bush Presidential Library and Center, The Farnsworth Art Museum, The Taiwan Museum of Art, Mellon Hall, Harvard Business School, The Henry Luce Foundation, Reader’s Digest Corp. and NASA Headquarters.

“She is, quite simply put, the world’s pre-eminent watercolorist, persisting over the past four decades in the mastery of her idiom,” Charles A. Riley, the director of the Nassau Museum of Art, wrote in a 2021 catalog essay, “To the Vanishing Point: Barbara Prey and the Art of Her Time.”

Prey often paints outdoors, inspired by the raw beauty of nature, the unfolding scenes she observes and the images they provide.

“It’s a number of things,” she said. “Sometimes it’s something that is just immediate and you see the light and you just know that it would make an amazing painting. And sometimes it’s something I’ve been thinking about for 12 years, and then I'll go back finally and paint it, or I’ve been looking and thinking. And then sometimes there’s a real personal connection to it — I might know the people. For example, if it’s an island, I might know the people who live on the island. So it really depends, but it has to be something that would be meaningful enough to really spend time working on the painting.”

Prey said there is a long tradition of American artists going out on-site to paint. But few have been women.

“To have a woman doing this and going to these places and painting is in some ways very unique — partly because there's a lot of gear to transport,” she said. “When painting on site I’ve had many disasters — I have had everything all fall over, my turpentine go into the water, wet paintings fall into the sand, bitten by ticks. You name it, I’ve probably had it, so you had have to be very flexible. You set up and you paint, and I’m usually painting all day.

“If a lobster boat is my ride to an island to paint, you want to make sure you can carry the wet painting back in between the herring and the lobsters. You have to be protected against all the elements as well, and you never know, it’s kind of serendipitous. It might be really windy and you’re not prepared for that.”

Still, Prey said she prefers to work on site as much as possible.

“It’s difficult as you battle the elements but there is an immediate and intimate relationship to the subject or idea that can’t be replicated in the studio, it’s fresh and spontaneous,” she said. “I’ve begun a summer series both in New York and in Maine (which has been an important inspiration for me) as well as a collection of works highlighting architectural village views and life out on the islands of Maine where I live in the summer. So many years spent drawing architecture and street scenes served as good training as well as the MASS MoCA architectural interior.”

“Osprey Nest,” which is 28 inches by 40 inches, is one of many outdoor landscapes Prey has painted. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

Like many artists and photographers, she finds the “golden hour” or “magic hour” — the time right after dawn and before nightfall — an especially enticing time to paint. She has worked then in many outdoor settings.

“That’s just so cool to paint with mountains and the snow, though, because you have the reflection,” Prey said. “And the light is great. I’m always looking for ideas and thinking and watching. And you know, you’re with nature and migrating birds and animals. It’s very rewarding in many ways.”

She has returned to a site several times to complete a painting.

“I like to finish as much as I can on site, but if it’s a large canvas, it takes a little longer,” Prey said. “So I’ll go back multiple times and paint the scene.”

Prey said she has not worked at night — not yet, anyway.

“No, I have not but I have done night scenes,” she said. “That would be fun.”

Prey said she doesn’t work from photographs to capture a night scene.

“I use my memory because the photographs wouldn’t work. I’m not that great a photographer,” she said. “I paint twilights. When I did the International Space Station, I had to do a night scene, so I spent a lot of time researching the stars and what the sky would look like.”

As a young artist, she had a summer scholarship at the San Francisco Art Institute, spending a summer there. Even then, she preferred to work outside.

“I was always drawing, and then I started to do the artwork for The New Yorker after college, they started to buy my drawings,” Prey said. “I have a lot of on-site New York street scenes from my travels.

“I’ve always worked on site, I’ve always worked out in the field,” she said in a January interview. “I’m going out to Jackson and Big Sky and Aspen next month and will take my paints. And I was just out in Sun Valley, but I was with my paints. So I go out and I ski and I also paint.”

Prey said she is always eager to create. It is ever present.

“I also travel with my oil paints,” she said. “I have a studio in Maine, so I’ll just come out early morning with the lobster fishermen and go out to an island and paint there for the day. It’s exploring.”

Prey said watercolor is a very demanding medium, which is perhaps why few persevere in that field.

“Color has always been important in my work and the transparency of watercolor creates a unique vibrancy,” she said. “I’m working in what has long been a male-dominated tradition and bring a different view and fresh eye to the medium. After close to 50 years of working with watercolor I’m always trying to explore new possibilities.

“I do oil painting as well as watercolors,” she said. “I did watercolors because my mother was such a fabulous oil painter that I didn’t want to compete when I was maybe 15. So that’s almost 50 years painting watercolors. Oh my gosh, that’s scary.”

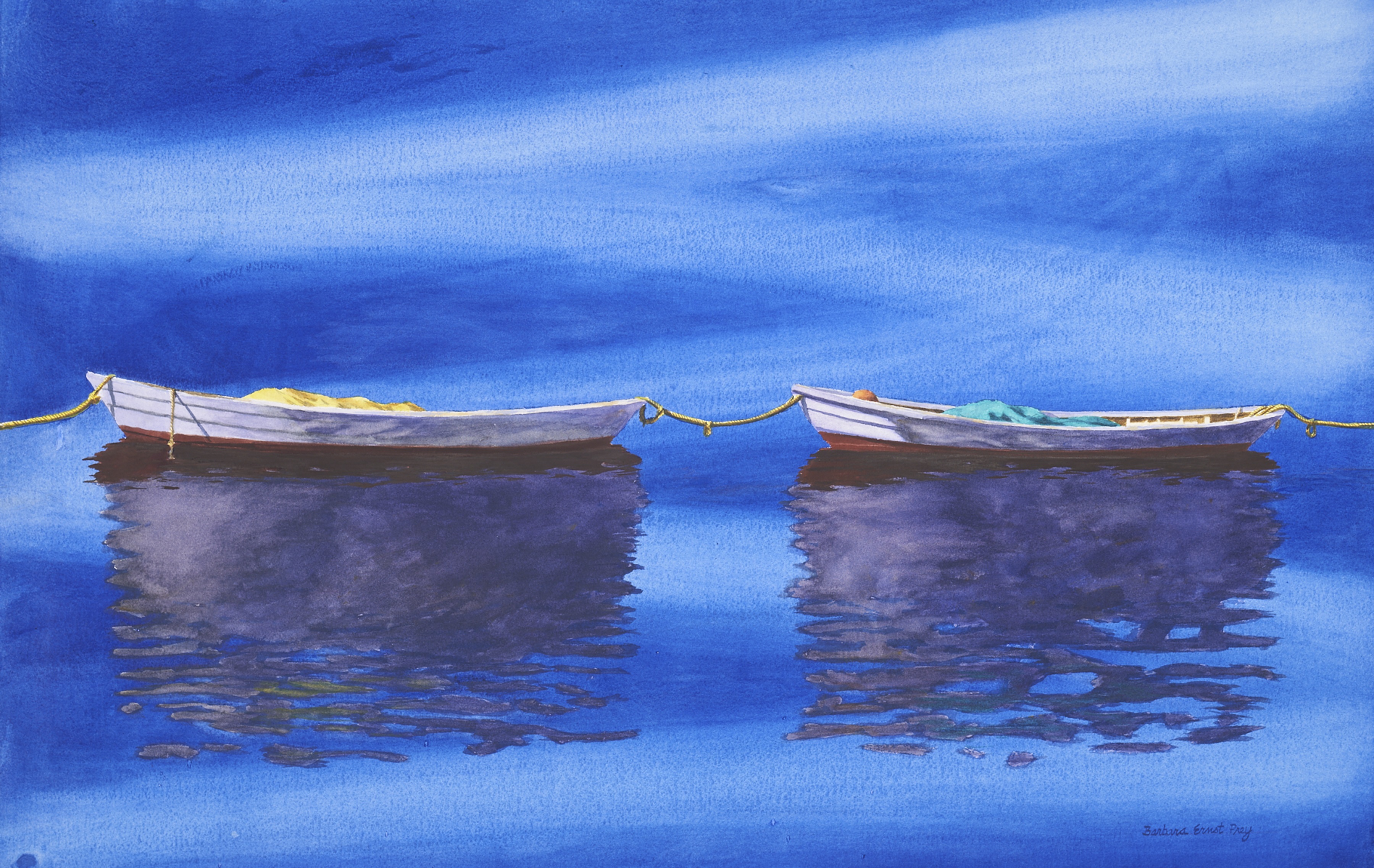

Prey’s painting “Social Distancing,” created during quarantine, depicts a favorite topic: The boats used by lobster fishermen. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

Mother inspired her

Prey grew up amidst art. Her mother, Peggy Ernst (née Margaret Louise Joubert, 1923-2005), set a quiet example by her work and approach to art. Ernst also had a successful textile design company before she was married, and created beautiful textile designs.

“My mother was head of the design department at Pratt institute in New York. She had a large studio in our home where I also had an easel set up to paint with her,” Prey recalled. “Growing up, she would take me out to paint with her on painting trips. She introduced me to the museums in New York whose collections were my early teachers. She was a great influence and role model — incredibly gifted, creative and she thought outside the box. For example, she made the kitchen rug look like a Jackson Pollock painting by splattering it with paint.”

“I grew up in a home that had a wonderful studio,” she said. “I had my mother as an inspiration. She would always paint on site so she would take me out painting when I was little. That’s really where I began and I would paint in the studio with her as well.”

Her first piece exhibited at a juried show at age 9. When she was 17, New York Gov. Hugh Carey purchased a painting for $50.

She studied art history at Williams College and did her honor’s thesis with Lane Faison, one of the original “Williams Mafia,” and “Monuments Men,” who became a mentor.

“After graduating from Williams, I had an internship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which continued to expand my painting vocabulary and was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to continue studying art and architecture in Europe,” she said. “While living in Europe, I worked as a personal assistant to a European prince and continued to paint and exhibit. I returned to New York City and worked in the Modern Painting Department at Sotheby’s — interestingly I am now included in exhibitions with some of the artists we sold at auction. At this time, I began to do artwork for the New Yorker (continued for 10 years) and other publications including The New York Times and Good Housekeeping.

“I then went to Harvard to continue my art history studies, always continuing to paint,” Prey said. “After Harvard, I received a year-long grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to live in Taiwan, where I started to paint my larger on-site artwork. I drew, painted, and exhibited throughout Europe and Asia and visited every museum I could, which was my continuing education.”

She has had numerous influences who have shaped her work and career.

“I worked at Sotheby’s. I’ve worked in New York, in galleries, and my mother would always take me to the museums in New York,” she said. “So I was really fortunate because I had this incredible vocabulary. As I said, I studied at Williams College and they’re known as the Williams Mafia, because they have sent so many professors to head major museums like the Guggenheim, MoMA, San Francisco Museum, Dallas. I had this incredible training in art history, and then I continued at Harvard and took a number of art courses. I’ve always been looking.”

“Arcadia,” a 29-inch by 40-inch watercolor landscape, was painted in 2017. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

While she is known for her landscapes, she has done other work.

“Actually, when I first started and I was maybe in my 20s, I did a series of portraits of princes in Europe, of their children,” Prey said. “I do paint people, but I’m known for my other paintings and landscapes — often large paintings 40, 60 inches.”

Prey’s career has been highlighted by numerous accolades and honors, including being commissioned by President George W. Bush and first lady Laura Bush to paint the official White House Christmas card in 2003.

“I was honored to be invited by the president and the first lady to paint official White House Christmas Card. A very small group of American artists are invited to do this,” she said. “I was told it is a national treasure which enters the permanent collection of the White House; I am one of two living female artists in the White House permanent collection. I was able to spend many hours drawing and painting both inside and outside the White House for this commission.”

A 2003 article in The New Yorker stated that “Barbara Prey, may be, at this moment, the most widely viewed painter in the world.”

Prey noted she created paintings bought and enjoyed by both Democrats like Carey and Republicans like both Presidents Bush.

“I spent a lot of time at the White House working with Laura and George for the White House Christmas card,” she said. “And yes, I have met Barbara Bush because they have a painting of mine in the Bush Presidential Library of Walkers Point, their home in Maine.”

She said art “really speaks to people in different ways. That’s what I found.”

Art history student, teacher

As an avid student of art history, she has shared her knowledge with people across the globe.

“For many years I’ve been involved with U.S. State Department’s Art in Embassies program and my paintings have been exhibited in Paris, Madrid, Prague, Oslo, Hong Kong and are currently on exhibit at the U.S. Mission to the United Nations in the ambassador’s office and lobby,” Prey said. “I’ve been invited to lecture about American art at the U.S. embassies for the respective cultural communities where my paintings were on exhibit and spearheaded a lecture program with cultural centers of Europe. In 2007, the National Gallery of Art curator Sara Cash curated my solo exhibition 'An American View' in Paris."

She was commissioned by NASA four times, and it’s some of the work she is most proud of, she admits.

“I’m one of a handful of American artists NASA has commissioned to document space history, and one of the few females,” Prey said. “The four paintings are the Columbia Tribute, to commemorate the anniversary of the Columbia tragedy; the International Space Station, which is on exhibit with my painting of the Columbia Tribute, at the Kennedy Space Center; the Shuttle Discovery Return to Flight and the X-43, the fastest aircraft in the world, included in the Smithsonian institution’s 12 museum traveling exhibit NASA|ART: 50 Years, and on exhibit at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. My NASA commissions were included in both NASA|ART: 50 Years and NASA|ART: 60 Years exhibitions.”

“Columbia Tribute,” one of four pieces she did for NASA, pays tribute to the seven astronauts who died in the 2003 space shuttle disaster. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

“She does beautiful illustrative work,” NASA curator Bert Ulrich said told the Associated Press in 2004. “She just seemed like the right artist to pay tribute to the mission, so we asked her again. We only do that occasionally.”

Prey said she wanted to focus on a moment of triumph — the launch at Kennedy Space Center — and not the tragic final moments. NASA provided prints to the family members of the Columbia crew.

“I had the families in the back of my mind,” Prey told AP. “I was thinking, ‘What would I want to hang on my wall as a memorial?’”

She said having her art seen by millions of people and displayed in such prestigious settings has been very fulfilling. There are some pieces she is especially proud of, but that changes.

“Sometimes you’re working on something and you’re so proud that you've accomplished something,” Prey said. “And then you’ll go on to the next thing and then you're really excited about something else. I’ve been fortunate to have some really incredible experiences.”

In 2015, Prey was commissioned by Massachusetts MoCA to create the world’s largest known watercolor painting for one of its new buildings that opened in spring 2017. The interior portrait was titled “MASS MoCA Building 6 Portrait," on long-term exhibit.

“It took two years of planning and 40 watercolor studies,” she said. “I’ve been painting in watercolor for over 45 years, and this was an opportunity to open up new, innovative and groundbreaking possibilities with the watercolor medium on a grand scale in American art. It is considered the largest watercolor in the world. I’m included with just a handful of artists — Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Bourgeois, James Turrell, Jenny Holzer and Laurie Anderson.”

Prey poses by “Building 6 Portrait: Interior" at Mass MoCA. It is believed to be the largest watercolor in the world. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

Prey poses by “Building 6 Portrait: Interior" at Mass MoCA. It is believed to be the largest watercolor in the world. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

It was a physically demanding project, as Prey examined the building while deciding how she would create the massive painting.

“I was fortunate to be able to spend a couple of months last fall, in the winter and spring drawing inside the building and trying to figure out the specific view that I would paint as the commission for MASS MoCA for the new space,” Prey said in 2016. “I am honored to be the only artist commission for the new building which opens Memorial Day weekend 2017. I was able to bring my sketchbook and pencils and had to dress in layers because it was really cold there with no heat but it was a great time to draw and observe the space uninterrupted. I left a bit dusty — but loved being the only person in the building as I was able to go all through it up-and-down on the various floors and really get a sense of the history and the space/feel of the place.”

Prey likes using strong colors, especially in her study of Maine landscapes: "A clear blue sky speaks to your soul — it’s like a piece of music.”

But she said her reputation for using blue was largely a surprise to her.

“When I had a big show in Paris at the Mona Bismarck American Foundation, the academic journal of the Sorbonne described my blue as ‘Prey Blue,’ the blues that I use when I paint water, I paint boats,” Prey said. “And actually, that was what drew NASA to contact me because they really liked the blues in my paintings when they commissioned me. I think that was a tag I got. I do like blue."

‘Until I die’

Since 2008 Prey has served as a presidential appointee to the National Council on the Arts, the advisory board to the National Endowment for the Arts. Artists are appointed for their achievement in the arts and advise the chairman of the NEA and vote on all of the grants for the arts in America. They also nominate the National Medal of Arts recipients for the presidential ceremony at The White House.

Prey drawing the X-43, the fastest plane in the world, before takeoff from Edwards Air Force Base. Prey has done four commissioned paintings for NASA. Photo courtesy of Barbara Ernst Prey

“My artwork is in museum collections including the National Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the White House, where I am one of two living female artists represented,” she said. “The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), and many other institutions. Other collections include U.S. presidents and dignitaries, European royalty, (and) celebrities including Orlando Bloom and Tom Hanks.

“Recently I’ve been included in a number of museum exhibitions with artists I’ve studied, admired, or influence my work including Matisse, Titian, Picasso, Miro, Kandinsky, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Ellsworth Kelly,” she said.

It’s not all politicians, government entities and celebrities. Prey also has studied and painted works depicting quilters in Maine, including "Reunion," "Reunion at Dusk" and "After the Rain," as well as pieces focused on lobster fishermen who are based in St. George, Maine. She has family ties to the area that date back to the 1700s.

The dories — small, shallow-drafted boats — she saw when she visited the area at the age of 18 drew her eye. At the time, she was not aware of her family ties to the location.

“They were new for me and I was fascinated by their shapes, reflections and lines, but also with their history and connection to the sea,” Prey told Los Angeles Times roving cultural correspondent Paul Lieberman on Jan. 18, 2006.

“They are a symbol of a way of life, a point in time. In our age of technology, the beauty of the dories is that they are handcrafted.

“To me they are an aesthetic object in themselves,” she said to Lieberman. “But they were also fishing boats and a metaphor for the harshness of the fishing life. A lobster fisherman friend, Sherwood Cook, had a beautiful dory that I used to paint and I have a model he made of it to scale which I use for some of my paintings.”

Prey and her husband Jeffrey Prey have had a home on Oyster Bay, Long Island, since 1996. They have a son and daughter, both grown. Both are very artistic; her son is a writer.

“They have all been helpful and supportive over the many years and I’ve taken them on many painting trips when they were young,” Prey said. “They’ve helped me title my paintings. Both children came to the White House with the artwork. I’ve done a lot of lectures for the State Department Art and Embassies program, and my family has come with me on that as well. They’ve been hugely supportive. They haven’t had a choice.”

She has a brother who lives in San Francisco. He also has not worked as an artist, but it has been a part of this world as well.

“He’s very culturally aware and he’s been a great supporter all my life,” Prey said. “You can’t help having grown up in our house not being immersed in art.”

She said she has always felt a pull to create, to draw and paint. It’s still there after more than a half a century of study and work.

“I think it’s what you’re called to do. It’s what I’ve been called to do,” Prey said. “I know it’s what I love doing. I get up every day very excited to do my job.”

Prey, 64, said she plans to work “until I die,” and said she has many canvasses to fill before that happens.

“I love doing it and I kind of feel like my career … I’ve had an amazing career,” she said. “My paintings are in incredible collections nationally and internationally, and my commissions have been amazing. I still have lots of ideas and am excited about things that will happen in the future.”