Next year marks the bicentennial of the birth of Frederick Law Olmsted, whose landscape architecture and parks continue to enrich the daily lives of millions of Americans, even though they may not know his name.

Olmsted designed and built public parks and spaces across the country, including New York's Central Park, Boston's Emerald Necklace, Chicago's Washington Park and the grounds of the White House and U.S. Capitol. He wanted America's cities to have beautiful green places where all classes of people could relax and mingle as they enjoyed natural settings.

Grounds of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

Today, as in the late 19th century, parks are vital for sustaining healthy urban life. The coming 2022 celebration will pay tribute to Olmsted and his parks.

The National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP) is dedicated to preserving Olmsted's legacy and supporting and sustaining the Olmsted parks. Along with other partners, the NAOP is coordinating national and local Olmsted celebrations.

Olmsted's background

Before he turned to landscape architecture, Olmsted was a well-known American literary figure, whose circle of friends included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville and Washington Irving.

For two years, he was an editor at Putnam's Magazine, a monthly devoted to American literature, science and art. Olmsted also wrote for The Nation, a weekly that he helped found, with a mission he described as a more thoughtful way to treat "the questions of the day," than the "imperfect, slip-shod, and inaccurate" treatment of daily newspapers.

Before becoming a landscape architect, Olmsted spent an improbably varied 20 years studying engineering and surveying, working in different professions and getting to know all classes of people. He traveled through Europe and wrote a book called "Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England."

In the Merseyside area, near Liverpool, he visited Birkenhead Park, England's first public park, which influenced his view of how beautiful landscapes can transform everyday life.

After England, he traveled through the Southern states, writing dispatches for The New York Times, describing the cruelty and harm to the slaves and the degradation of living standards of the entire population as a result of the slave economy. Three books of his observations and a fourth summary volume, "Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller's Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States," were important in shaping the political thought of the period.

An influential abolitionist thinker, Olmsted opposed the expansion of slavery westward and raised money for anti-slavery fighters. He also argued for the integration of Black soldiers in the Union Army.

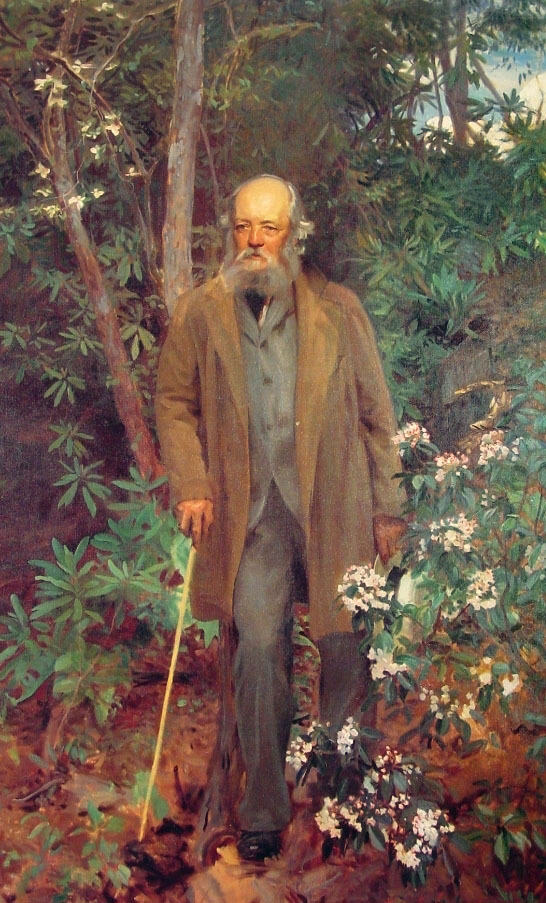

John Singer Sargent painting of Olmsted at the Biltmore Estate Museum in Asheville, North Carolina. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

John Singer Sargent painting of Olmsted at the Biltmore Estate Museum in Asheville, North Carolina. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

In 1861, Olmsted was selected to head the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a civilian organization authorized by President Abraham Lincoln to supervise the treatment of wounded Union soldiers, inspect army camps and aid returning soldiers. The Sanitary Commission also raised millions of dollars for needed supplies and is considered a forerunner of the Red Cross.

The governor of California drafted Olmsted in 1864 as head of a commission to study the newly created Yosemite park. Olmsted's report, arguing for the preservation of the park's beauty and wilderness and against industrial use of the area, was initially suppressed by others on the commission but later became the philosophical foundation for the National Park System.

Social reform and parks

Olmsted wanted to effect social change for the betterment of the nation and saw public parks as central to the process of democratization and protection of the health of citizens.

In his draft charter for Yosemite in 1865, Olmsted wrote plainly that it is a "political duty of republican government" to establish public grounds for recreation and enjoyment.

Yosemite National Park, which Olmsted's 1865 report advised to be kept as a public preserve. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

Yosemite National Park, which Olmsted's 1865 report advised to be kept as a public preserve. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

All his travels and wide range of work experiences philosophically prepared Olmsted for beginning the completely new profession of landscape architecture, which he undertook in 1858 at the age of 36, along with his colleague Calvert Vaux.

Olmsted wanted the parks and spaces he designed to have a restorative effect on the minds and bodies of all classes of people, a process that he thought would occur unconsciously, aided by landscape design. His parks are living examples of his design philosophy, but he also left a vast collection of writings and notes spelling out his design principles.

`Olmsted 200'

Today we have an immense library of documents, plans and correspondence as resources to learn from Olmsted and his more than 500 landscape commissions. Olmsted's works, already in 12 printed volumes, will be available in digital form next year.

Many more resources exist on the websites of NAOP and Olmsted 200.

Olmsted's parks and spaces are available to all to appreciate, explore, and, if needed, to help maintain and restore.

Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

For those who want to learn more about Olmsted, NAOP, and the Olmsted 200 group have organized the information and activities that will bring his legacy into more prominence.

Continuing the Olmsted legacy by celebrating our parks

Kinute interviewed Anne “Dede” Neal Petri, president and CEO of the National Association of Olmsted Parks, based in Washington, D.C., in July about the Olmsted 200 project.

What is the mission of the National Association for Olmsted Parks?

The National Association for Olmsted Parks was established in 1980 as the first--and we are still the only--national organization dedicated solely to protecting and promoting the life and legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted. We have been on the front lines of supporting and defending Olmsted parks and places since then. We believe these spaces truly are urban necessities and that they are beautiful, adaptable and make our cities more livable. City dwellers surely confirmed that view during the pandemic.

We all appreciate Manhattan's Central Park today. But back in 1980, when NAOP was founded, Central Park was suffering from crime, garbage, graffiti and decaying infrastructure. That was one of the reasons NAOP started. We needed to remind people that Olmsted parks aren't self-sustaining, that they require attention and care. We were focused on helping concerned individuals organize to support and sustain these beautiful parks and places-- as friends groups and conservancies.

An overview of Central Park in New York City, New York. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

Betsy Barlow Rogers, the first Central Park administrator and founder of the Central Park Conservancy, really set the bar for showing how engaged public officials and citizens can come together and renew and sustain these spaces. That’s something that we hope will be a lasting message: we do need to support these spaces for the future.

Olmsted 200 is coming up, and we'll be hearing more about him. How is the NAOP getting local communities involved?

Olmsted 200 will be celebrated in 2022, which is the bicentennial of Olmsted's birth. NAOP is honored to be working with nine other national partners. We have launched a website called Olmsted200.org, with a national calendar as well as a dynamic blog.

We are reaching out to communities across the country to encourage them to engage with the celebration.

To help them, we offer toolkits and resources with ideas ranging from community outreach (such as clean-up days or park summits) to advocacy tools and template proclamations for FLO Day, April 26, 2022. There is no one-size-fits-all. We want communities to make this celebration their own.

In Rochester, Atlanta, New York, Boston, Chicago, Milwaukee and Southern California, NAOP has helped bring regional groups together to brainstorm. As a consequence, at the local level, we are seeing a wide array of activities ranging from park restoration, to walks and talks, to park cleanups, to exhibits, to academic conferences. Our goal is to post these activities and events on the website, www.olmsted200.org, so that people can participate, from coast to coast.

We have student resources, and I particularly recommend a special coloring sheet depicting Frederick Law Olmsted for younger children. We also have wonderful Olmsted Halloween masks that you can print out.

On the serious side, we are sponsoring an essay competition about the enduring relevance of Frederick Law Olmsted for secondary school students as well as those in college and graduate school. The deadline is Jan. 15, 2022.

What are some threats facing historic parks and landscapes around the United States?

Olmsted parks and places face multiple threats--from development and shrinking municipal budgets to lack of understanding about their design and the designs’ unique value. Olmsted regularly bemoaned public officials who viewed parks as places to build. And we see public officials too often appropriating public parkland for private uses. Those are continuing challenges that we are facing across the country.

How is the NAOP helping communities restore and maintain their Olmsted spaces?

We serve as a resource for the Olmsted network of parks and places across the country. To that end, we offer educational, technical and advocacy assistance to over 80 organizations.

One invaluable resource is the "Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted," published by Johns Hopkins University Press. Working with series editor Charles Beveridge, NAOP is pleased to have helped sponsor these volumes. It’s a foundational resource for those who are rehabilitating and preserving Olmsted spaces.

Olmstedonline.org is a digital resource that offers plans, drawings, correspondence and historic photographs of about 6,000 projects that Olmsted and the Olmsted firm did over 100 years.

We have a strong advocacy effort. For instance in Riverside, Illinois, which is a planned community designed by Olmsted, there has been a proposal to put up a flood wall, and we have raised real concerns about this solution. We're urging them to look at green infrastructure and other less destructive options.

Whether it's in New Jersey or Illinois, we've often opposed projects that involve intrusive development inside scenic parks and scenic reservations.

Jackson Park in Chicago, Illinois. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

We also have regular publications. Our Bulletin appears monthly. Field Notes comes out twice a year, with reports from the field. In this way we can share best practices.

We foster scholarship. We are very excited to be working with the University of Virginia and their online imprint to digitize 10 volumes of the Olmsted papers in time for 2022. We know that this will really help researchers with these thousands of documents over time.

Long-term, we're working to educate the public about the important legacy of Olmsted's work and the design principles behind it.

That's wonderful that his papers will be digital.

Yes, we're really happy about that. It's nice to have the printed editions to be sure. But what we learned during the pandemic was that often people could not obtain access to the printed copies. So having these digitized is going to be a major step forward.

How would you characterize what's unique about the Olmsted-designed landscapes?

Olmsted understood that thoughtful design has positive health, ecological and civic impacts on individuals and their communities.

He lived from 1822 to 1903, and during this time America was moving from a rural, agrarian society to an urban one. The population went from around 10 million to 75 million in one lifespan.

Olmsted was living at a time of considerable change, and a time that has many parallels to today. He saw the public health challenges of urbanization, including widespread disease (smallpox, malaria, yellow fever, tuberculosis) and poor sanitation. He saw deep social and racial divisions evidenced by the Civil War.

Olmsted brought all of these experiences to his thinking about park making. And he viewed parks not as just green spaces, but as restorative in nature and providing park-goers a healthful space and an enhanced sense of freedom.

These were carefully designed places that served a variety of purposes--social, psychological, civic and health related. Olmsted’s designs worked subconsciously to restore and refresh; they offered pastoral and picturesque vistas and places where one could walk or ride without distraction. They invited people from all walks of life to come together as equals. These were quintessential “democratic spaces,” and that is one of the unique goals of Olmsted’s parks.

All of these features of Olmsted's parks are as important 150 years later as they were when they were designed.

They certainly bring beauty! What about the impact of Olmsted parks on the environment and environmental habitats?

Today, we are rightly concerned about ecological issues. The environmental benefits of Olmsted parks are considerable. Indeed, in many respects, Olmsted understood green infrastructure before we called it that. If you look at the Back Bay Fens in Boston’s Emerald Necklace, Olmsted took an open sewer and created a natural wetlands that would serve as a healthy water management system.

His parks function as sponges for water runoff. The tree canopy helps drop ambient temperatures and offers habitat for birds and wildlife. In all these ways, Olmsted’s parks contribute to more livable cities. And while he doesn’t often get credit for it, Olmsted was also a practitioner of conservation-minded design. In the semiarid West, he advocated the use of native plants rather than water-dependent grass lawns.

It seems that it's as important today as then to have Olmsted-designed parks and landscapes in urban areas.

When we look at our cities, it would be hard to think of New York City without Central Park, or Boston without the Emerald Necklace or Brooklyn without Prospect Park.

Prospect Park in Brooklyn, New York. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

One of the challenges of all Olmsted parks is that they're so natural! We discovered that people take them for granted; they think they were always there. And they don't realize that these spaces were constructed from scratch, that they are part of the built environment.

So that again is one of the ongoing challenges and opportunities for NAOP and Olmsted 200, to really emphasize that these are spaces that have come to us through decades of commitment and that they will require decades and centuries of commitment going forward.

During the pandemic, you could see the role of parks in helping people survive--people otherwise stayed inside.

It really underscores how visionary Olmsted was. That was really what he was thinking in the late 19th century. Many individuals were living in tenements. These were very small and unhealthy living spaces, and Olmsted espoused the therapeutic benefits of access to nature and the outdoors.

He wanted all people to have access to open spaces. He wanted people to be able to be seen together, of all classes and all backgrounds. There was a unique mental and physical benefit of these spaces for community well-being.

Olmsted had a philosophy called "communitiveness." He sought to employ soothing and restorative landscape designs to give city dwellers respite from the cares and the stresses of urban life. It was Olmsted’s hope that the thoughtful built environment could restore people and help “soften” their interactions with one another and make for a vibrant civil society. It's certainly a vision that is desirable today.

In his time, parks were mostly for rich people, in England, for example.

That's absolutely right, and I think we take that for granted today. But it was really Olmsted's idea that parks should be for all people, that they were democratic spaces.

He was inspired in the 1850s when he went on a walking tour in England and Europe and saw Birkenhead Park in Liverpool. This was a very unusual park at that time because it was a public park open to all. As he saw this, he began to mull in his mind the idea of making this an essential component of American life, what he called “a democratic development” of unique significance and importance.

So what did he do? He came back and, in time, took this vision of a democratic space and parks for all and put it into play in communities across the country.

He was remarkable in his compassion and empathy for all types of people.

It's interesting to look at his career. He gives hope to all late bloomers and was surely lucky to have a father willing to support him as he looked for his ultimate career. But as a consequence, Olmsted did gather valuable experiences from his encounters with individuals across the country.

He tried life as a surveyor, he spent a year on a ship going to China, he tried to work as a scientific farmer, he was a reporter for The New York Times examining the South and slavery, and he worked as the first head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. So he was really engaging with people from all walks of life, with different professions and occupations and different parts of the country. He was accustomed to engaging with people who had diverse experiences, and he saw the value of bringing diverse peoples together in his parks.

He reminds me of the social reformers of that day--the social workers and settlement houses--in his views of community.

I think that's right. We often think of Olmsted as a landscape architect and a park maker, but park making was just one component of his vision of social reform.

Particularly in the wake of the Civil War, he was looking for ways to bring people together. He thought that public parks were one way to make that happen.

When he was in California, he was put in charge of a commission to look at Yosemite, and he and the commissioners issued a report which called on the preservation of scenic reservations for all Americans. So there too, we can give Olmsted credit for conceiving of what eventually became the national park idea.

As Olmsted saw it, these parks were to belong to all people, in essence to be part of the American patrimony and key to the “pursuit of happiness.”

Can you tell us about the Inspired by Olmsted competition that you're sponsoring?

When the Olmsted 200 planning got underway, it was just as the pandemic was unfolding. So we were asking ourselves: what could we do that would be enjoyable if we were social distancing or not. We concluded that there were many Olmsted landscapes of every kind with carillons and what a wonderful opportunity to sponsor a competition called "Inspired by Olmsted" for carillon where in 2022 the winning compositions could be played in landscapes across the country.

July 1 was our deadline, and I'm happy to say that we received a wide array of submissions. We have an expert jury that will be looking at these, and we'll be announcing the winners in early 2022. The website calendar ... already lists many exciting concerts, and I urge people to find a concert near them.

What are some of your goals for the future?

The bicentennial offers an excellent opportunity for NAOP to redouble our campaign to create strong advocates for Olmsted parks and places. And as I discussed before, these spaces are facing threats, whether it's from development or shrinking budgets, and so we see our role in drawing attention to the immense economic, social and health benefits of these historical and natural assets.

Sheep Meadow, Central Park in New York City, New York. Photo courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

As we look ahead, we'll continue to offer advocacy, research and education to protect, restore and maintain these Olmsted parks and places. At the same time, we realize that not all communities have access to well-maintained parks and green space. So NAOP and Olmsted 200 are working hard to advance community input and engagement to achieve equitable access for all people. We can do a better job of ensuring that all communities feel comfortable in our parks. And we are working hard to address the most responsible ways communities can adapt and update their parks in the face of new cultural and social demands while remaining true to Olmsted’s vision.

Do you have suggestions for how community residents can contribute to their local parks and landscapes?

We invite everyone to join the Olmsted 200 celebration. You can go to the website, Olmsted200.org, and sign up for our newsletter, Olmsted Insider, and there are some wonderful opportunities for communities across the country.

On the calendar, you can see, for example, that Riverside is doing seed collection; other parks are doing tours. We are encouraging communities to brainstorm and use Olmsted 200 as an opportunity to engage with their parks in creative ways that will seek community-based input and programming.

We have a social media effort underway now called "#Picmpark." We're encouraging people to photograph their favorite park and send us those photos, and then we select a wonderful photo each month. Winners receive a gift from our Olmsted 200 shop where you can find hats, picnic blankets, walking sticks and special Olmsted T-shirts for children. I encourage people to visit.

To me, Olmsted ranks as an American hero, unique all around. His life is well worth reading about.

Yes, he had an immense impact on the late 19th century, whether because of his experiences as a park maker and landscape architect, New York Times reporter helping document the horror of slavery, as the first head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was tasked with improving health and sanitation for Union soldiers, or head of the Yosemite Commission, looking at the important role of scenic national parks for all Americans.

He was really engaged in so many different ways with key parts of our history—public health, urbanization, the abolition of slavery, city and regional planning, college and school campus design. I think sometimes we don't know enough or appreciate enough his many touches on 19th-century America—and, more importantly, how his work and his vision continue to make our lives better today.