On most days in Laikipia County, Kenya, the wind sweeps down the mountain ridges into the plains whispering the promise of rain.

One of the wettest regions of the East African nation, the Laikipia County area sees rainfall even in its driest months. That is why, in many of the local images taken by and of esteemed wildlife sculptor Murray Grant, clouds bubble and brew on the distant horizon—a perfect backdrop for Grant when he is in his element, sprawled on his stomach, observing a spiral-horned antelope as it rifles through the prairie grass or lingers at the waterhole.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

A lifelong resident of Kenya and director of the El Karama Lodge and Conservancy in Laikipia County, Grant received notoriety for his ability to re-create African wildlife in an eternal bronze form that features breathtaking detail starting at the individual hairs in an animal’s fur down to the wrinkles in its muzzle.

A fascination with biology

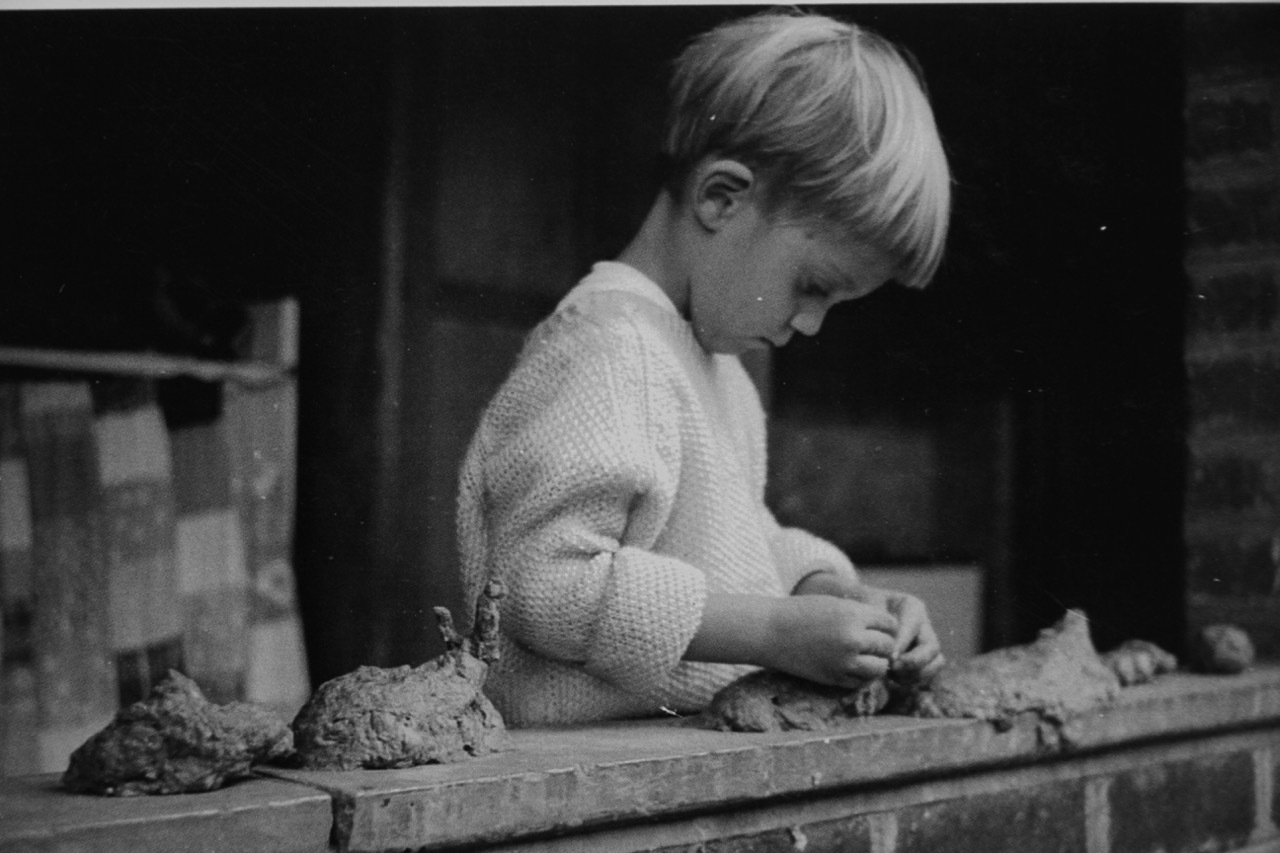

Grant credits his lifelong passion for sculpting to his mother and father.

“The lifestyle and place they chose to raise me were the key cornerstones to my beginnings as a wildlife sculptor,” he said.

Grant was raised in the remote and wild expanses of Kenyan bushveld at a place that was called El Karama Ranch, which he eventually turned into the El Karama Lodge and Conservancy. These lands, he said, were always rich with wildlife.

“These animals were the most exciting feature in my upbringing,” Grant said. “Hunting with my father and drawing with my mother stimulated the beginnings of the powerful obsessions and daily immersion in wildlife necessary to become a wildlife sculptor."

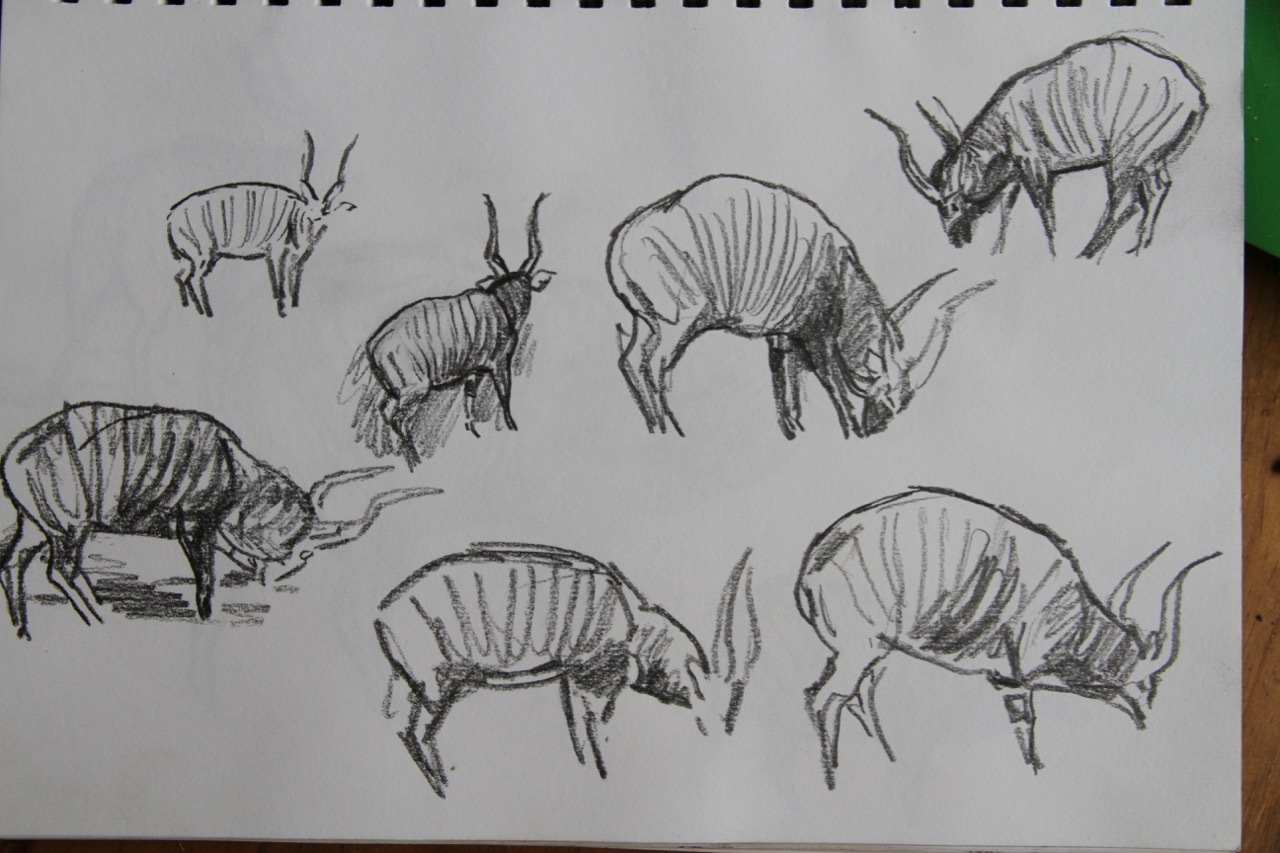

While he is an artist at heart, Grant’s work celebrates biology. Whether the lumbering stature of an elephant, the muscles rippling over a leopard’s shoulders or the magnificent curling horns that crown the heads of big game, Grant breathes artistic inspiration into a cut-and-dry scientific concept: anatomic accuracy.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

“I think my recent bronze of a Central African Lord Derby eland typifies what I’d be proud to produce more of,” the sculptor said. “Anatomically accurate sculptures that portray something of the character, beauty, environment and physical presence, perhaps spirit too… an accurate record of just how that eland looked ghosting through his dusty northern Cameroonian savannah.”

For those on the Western side of the great Atlantic pond, an eland is a common species of antelope native to East and Southern Africa.

It may be easy for an observer to compare Grant's realistic work to outlandish, dreamy, whimsical renderings of animals and wonder where the excitement and prestige are in creating precise sculptures that are perfectly proportional to what the creature looks like in reality. You might dare to say that these anatomically correct pieces are easier to create than a Picasso-esque approach where the art of life is viewed through a shattered lens.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

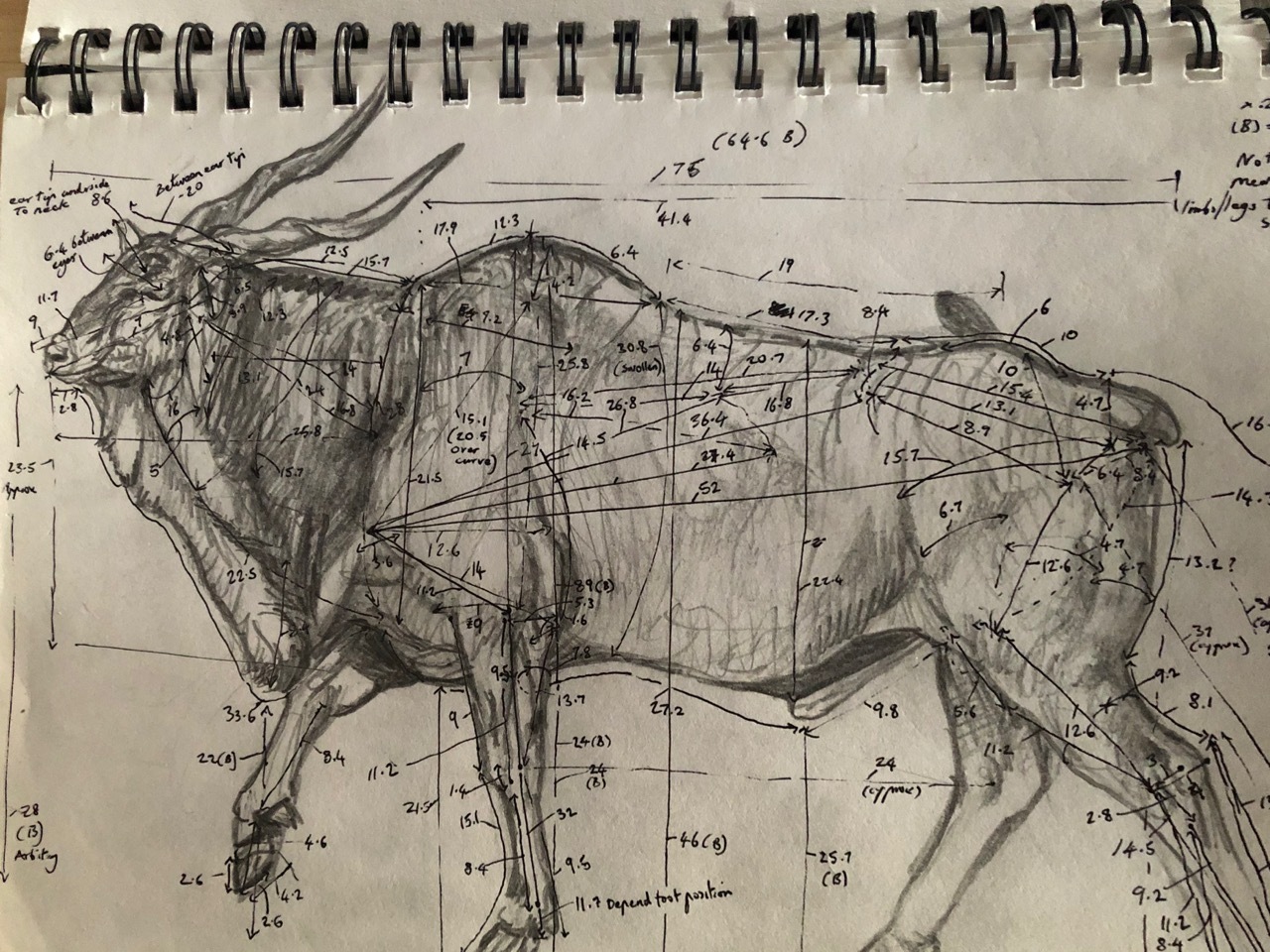

But a look into Grant’s sketches would swiftly prove you wrong. While the difficulty of any type of art is subjective, in no way can Grant’s art be described as "easy."

The sculptor’s sketchbook, no doubt crusted with dust from hot, arid African gales and dappled with dried raindrops after being at Grant’s side for every adventure, depicts pencil drawings that even done in the most urgent rush are impressively accurate.

Criss-crossing over the pencil drawings are webs of hand-drawn angles, measurements and arrows. Grant, giving the world’s best tailor a run for their money, notes the size of an antelope’s haunch, the breadth of its chest and every measurement in between on his sketchbook.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

And meanwhile, scarcely takes his eyes off the beast at all.

“My bronze and sterling silver sculptures have so far been almost entirely of African wildlife species,” Grant explained. “Typically, I try to represent them faithfully, pushing the boundaries as hard as I can to make them really feel alive through realism. This comes from a no-short-cuts perfectionist approach with lengthy background studies.”

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

It may be weeks, months or even years of painstaking research, sketching, ecological and anatomical study, and simply sitting in a field watching a creature live its life before Grant heads to the forge to begin the animal’s sculpture.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

Not every aspect of Grant’s work is glamorous, or even enjoyable. For one, the first thing he is normally greeted with in the morning when he steps foot outside of the El Karama gates are the fresh piles of buffalo or elephant dung from the night prior, landmines that will ruin your shoe and your entire day if unnoticed.

Adding to that, the sculptor dryly referred to the background studies as “the fun bit” in his projects’ timelines; while long hours of research and stacks of notes may carry the same level of appeal as a root canal, the desk work pays off when Grant gets to travel to the continent’s most remote places—areas he described as the “far-flung corners” of Africa, such as the high-altitude habitat where he pursued his ultimate muse, a leopard—to sketch, photograph, hunt or simply observe an animal in its natural state.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

Tales from Africa

In those African corners Grant finds treasures and memories he will never forget—some that are endearing snippets of life in the wild and some that instill a sense of awe that rightfully borders on intimidation.

Out here where nature has full reign and powerful animals roam, Grant feels somewhat safe… but not entirely.

“This environment can potentially throw some of the scariest wildlife encounters imaginable at you around every corner. If you use your inherent and learned knowledge, you can be perfectly safe out there,” Grant explained. “You find an intoxicating and addictive state of mind balanced between nervousness and confidence that allows you to feel completely alive and stay that way as you wind your way between greater and lesser beasts.”

Grant sees memorable things out on the African savannah every day and could recall many instances where he witnessed something that would have brought a city dweller’s heart into their throat.

“I could think of many dramatic occurrences, like watching two old buffalo bulls knock the hell out of each other for an hour,” Grant reflected, “or the repeated charges of a big bull elephant that came so close he threw dust over me.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

“These were inspiration in its purest form.”

Unforgettable moments in the wild don’t always have to be a theatrical fray of blood and dust, though. Equally as memorable and inspiring are the peaceful, ordinary scenes of animals in their natural daily routines such as, as Grant described, “the beauty of a herd of impala painted by the evening light,” with the soft call of a ring-necked dove signifying that the day is done.

For Grant, these moments carry the same value in being remembered as the ones born of conflict and danger.

Canine companions

Grant’s adventures would not be complete without a four-legged friend by his side. The sculptor has always been accompanied by a dog, usually a bull terrier or Staffordshire terrier of some sort. Dogs, he explained, carry a level of instinct that humans don’t and often notice things among the brush before their owners do.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

“If you walk into the wind through the bush and are in tune with your dog’s behavior, he is an unbeatable early warning system,” Grant said. “You will see him catch the scent and probably exchange glances.”

Grant was once saved by his furry companion after being knocked to the ground by a buffalo, an encounter that's described as “joining the bashed-by-buffalo club.”

“Nothing like a plucky little dog to get a dangerous game animal’s attention in a pinch,” Grant said.

Man’s footprint in no-man's-land

The hand of humankind is swift and merciless in its destruction and alteration of the natural earthscape in Africa.

That is why wildlife and habitat conservancy are the mission at Grant and El Karama’s core. The sculptor has watched massive stretches of pristine wilderness devoured by humankind’s hunger in his lifetime living in Kenya.

“God’s creation before this happened seemed somehow so ordered, so balanced and beautiful,” Grant said. “It crushes my soul when I see it cut down, built on, changed, planted, fenced, rearranged, ordered and ruined before the ceaseless march of the race of men.”

Following the ruthless deforestation is the cutthroat practice of poaching and trophy hunting, a crime that Grant says he will someday attempt to capture in his art to show humankind forever what they’ve done.

Hunting can be done in a way that is respectful and balanced with the animal kingdom and nature, Grant said.

“Strangely, to get away from some of that I often find myself in some very remote and pristine wild places, which is most often a well-managed hunting concession,” he explained. “I respect the management of these places and pray that they survive for posterity as places rich in biodiversity, but also where man can still find somewhere to get aware from his mess.

“One sure has to travel further these days to find them.”

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

Preservation and sustainability of a thriving African and Kenyan ecosystem is still a focus for the El Karama Lodge even as it grew from a cluster of pitched tents and open fires to be an exclusive lodge and holistic cattle ranch on 14,000 acres of conservancy land.

“Wildlife art plays its part in supporting the conservancy, but as to why I focus on it, that is more simply answered: my wildlife art is an expression of my fascination with wild animals, it is absolutely my calling and the in-depth studies and interaction are part of that same calling,” Grant said.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

Inspiration lives in the wild

Grant’s day starts as dawn begins.

In the light of the blood-red African sunrise, he walks the game paths that wind around the lodge’s perimeter. Heavy rifle in hand and sketchbook slipped into a pocket, Grant makes his way from the rocky ridges, to the wooded sandy-bottomed gulleys, across the plains and riverine brush that he knows as home.

If the sculptor is not feeling brave enough to be on foot as he traipses the Kenyan bushveld, he will instead head out in the Landcruiser with his Canon to do a bit of photography.

Escape via four wheels is faster and more successful, after all, than escape on two human feet. The sense of danger may ebb and flow in the wild-lands, but it'll always be just present enough to raise the hairs on the back of your neck.

Despite seeing the same highlands, the same species of animals and the same sprawled horizon every single day for decades, these African scenes remain Grant’s daily source of inspiration, a passion that the sculptor described as ancient, noting that prehistoric hunters also took to their cave walls to draw the animals they knew and loved.

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

While every creature sparks joy for Grant, if forced to pick his greatest muses the sculptor would choose leopards and Cape buffalo, animals that he says never stray far from his mind both in waking and sleeping hours.

The Cape buffalo, a huge and brute species of game, is an animal viscerally connected to Grant’s daily life in the bush. It demands attention, he said, attention that should be ignored only if one finds their life to be expendable.

Having studied, re-created and hunted the buffalo for population control and meat, Grant believes the Cape buffalo is owed respect, so much so that his first five bronze statues were all of the buffalo.

“[The buffalo] found a hunter in me who developed a profound love for this tenacious and beautiful wild bovine beast,” Grant said. “I will never stop sculpting him.”

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

A very different sort of animal that comes with a unique set of fascinations and challenges is the leopard.

“They are my nemesis,” Grant said fondly. This big cat is the most challenging animal to do justice for in a sculpture because of its incredibly supple and highly defined musculature, “which is camouflaged impeccably by nature’s most beautiful and finest spotted robe,” Grant said.

“The challenge doesn’t stop there, though,” he continued. “They are so elusive that, unless I go to great pains to study them, all I might get is to listen to their guttural grunting on an El Karama evening.”

Continuing on the mission

Life is an incredible adventure for this Kenyan wildlife sculptor.

Grant has accomplished a lot in his years, but he’s not done yet. He has high goals for his art in the next decade.

“I’d like it to reach a greater audience,” he said, “and I’d really like to create some monument-sized, high-impact pieces that work to promote the inestimable importance of wild game and wild spaces and perhaps some of the challenges that they face as well as their raw beauty.”

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

The sculptor said he’s where he is today through a lucky combination of chance, commitment, friendship, curiosity, passion and determination.

“I was proud to have got myself here and gotten the exposure I needed to produce my best standard of work,” Grant said. “[...] to photograph Lord Derby Eland on foot and from the air, to hunt and to study their anatomy in depth, to create field reference molds and casts and totally immerse myself in learning this most majestic and least seen of all Africa’s spiral horned game animals.”

Photo courtesy of Murray Grant.

Grant encourages everyone to come and respectfully visit the vibrant, enthralling lands of Africa before these places disappear or change forever. A good start? The El Karama Lodge and Conservancy.

“Just by visiting you help create a value for these places and the wildlife who live here,” Grant said. “So come and have a serious adventure.”

For more information on Grant and his sculptures, visit Murraygrantbronzes.com or find him on Instagram @Murraygrantbronzes. For more information on El Karama Lodge, visit elkaramalodge.com or find them on Instagram @elkaramalodge.