The widespread introduction of non-native ornamentals and the proliferation of suburban lawns have seriously upset the environmental balance by driving out insects that thrived on native plant species.

The result is environmental "dead spaces." These are areas where pollinators and insects—a crucial part of the food chain from birds to small mammals and on up the ladder—have disappeared from the landscape.

Entomologist and author Douglas Tallamy proposes a practical way that anyone with a patch of outdoor space can help restore environmental balance: Reduce your amount of grass, plant some keystone native species and change outdoor lights to yellow.

These simple measures can bring back lost insect populations and thus replenish the food web, starting from the bottom. Native plants transfer energy from the sun to feed native insects that then feed birds and so on up the food chain. Native species will return as soon as the native plants that support them are replanted.

Douglas Tallamy has taught in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware for 40 years. His books summarizing his research on native plants and wildlife and encouraging the planting of native species include The New York Times 2020 bestseller, Nature's Best Hope.

Douglas Tallamy. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

He shows that the non-native plants and lawns that have taken over the U.S. landscape are the main culprits in biodiversity decline. Most native insects, including our pollinating bees, don't feed on the aliens. Without proper food, insects disappear. Without pollinators, many flowering plants die out.

Tallamy acknowledges the "pox we have delivered upon the environment and thus upon all of our houses" in Nature's Best Hope, including as he says, changing our climate "for centuries to come." But his main focus is on a "cure for that pox": How we can turn the situation around.

Tallamy gives us a new appreciation for insects, "the little things that run the world," according to a favorite quote by the biologist E.O. Wilson. We learn that a mother chickadee feeds her young thousands of caterpillars before they're out of the nest. And we learn that there are keystone plant hosts for insects, like the mighty oak, which hosts 557 species of caterpillar.

Carolina chickadees feed their young up to 9,000 caterpillars before they leave the nest. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

A Homegrown National Park

Tallamy's goal is to repopulate native species of plants and animals backyard by backyard. As more people catch on to the idea, he hopes his Homegrown National Park will take shape, creating a network, piece-by-piece, across the country.

Our existing National Parks and natural areas are not enough to restore biodiversity by themselves, Tallamy says. Our backyards, even if tiny, can supplement the natural habitats for a diverse number of species. Cutting privately owned lawn space in half across the country, he says, will provide us with 20 million acres of productive natural landscape and help reverse what he terms an "ecological crisis."

Tallamy came up with his idea after observing the vegetation and insects on the 10-acre farm he bought about 20 years ago. He noticed that alien plant species weren't eaten up by insects, as the native plants were. Over the next few years, Tallamy's entomology students conducted controlled field experiments to see how this worked and to quantify insect and host plant data for native and alien species.

They found that the insects showed a clear preference for the native plant species.

Not all entomologists agree with Tallamy's thesis. For example, ecologist Arthur M. Shapiro, of the University of California Davis, has studied butterfly populations for decades and says there are many factors that contribute to the monarch decline and we don't fully understand it. Shapiro also cites examples of West Coast insects that adapt to introduced Asian species of plants.

A Doable Remedy

Tallamy's prescription for restoring our damaged ecosystem is doable. It doesn't require ripping out all our flowering alien plants; it does require gradually bringing in some keystone native plants, and reducing your amount of lawn.

If you're concerned about biodiversity and bringing back a balanced ecosystem, adding your piece of yard to the Homegrown National Park is a viable contribution you can make to reversing the damage. Tallamy's books are a good guide to all the relevant plant species and insects to help you grow native most effectively.

Fixing Our Ecological Problems By Enriching Life on Earth

Kinute spoke with Douglas Tallamy June 11, 2021, to ask him about the causes and dimensions of the current ecological state and what each of us could do to help fix it.

What simple steps can homeowners take to support insects and pollinators, and encourage wildlife and biodiversity?

There are several things. Most homeowners have way more lawn than they need. Lawn is a plant you should have where you walk, because you can walk on it without killing it. But that's the only place you should have it, because it's a biological dead space.

I talk about cutting lawn area in half, and that means you're going to put a lot more plants in those spaces. Some of the plants you should put there are what I call keystone plants, the ones that make most of the food that support our food web, such as oak trees. Oak trees are the top keystone plant in most of the country.

Oak trees are the most important keystone plants in 84% of the country. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

Turn out your night lights, which are a major cause of insect mortality. You can do that by putting a motion sensor on your security light. Or you can exchange a white light bulb for a yellow one. Yellow wavelengths are not very attractive to insects.

Most people have invasive plants on their property, either ones hiding in a corner or part of a hedgerow or part of the design to begin with. A lot of our ornamental plants are invasive -- like Bedford pear, burning bush, barberry, porcelain berry. They should be removed because they don't stay on your property; they escape and pollute the natural areas. You want to replace them with the best native plants that support our wildlife.

If everybody did that, we'd be a long way toward reversing our insect declines.

What plants should people start with?

Start with the ones I'm calling keystone plants, and that changes as you move about the country. We have a tool on the National Wildlife Federation website called Native Plant Finder. You can put in your zip code, and the best plants for supporting your local food web in your county will pop up. That's the easiest way to find your powerhouse plants.

What advice would you give to a new homeowner about landscaping?

I'd say that the property you just bought is an important part of the future of conservation. In the past, we thought that nature was someplace else--humans were here and nature was someplace else. But there isn't "someplace else" anywhere. And we can't afford to lose the natural world that supports us. That's our life support system.

We have to coexist with nature. Homeowners should accept that if they're going to take on the responsibility of owning part of the Earth. It is ethically and ecologically irresponsible to kill it off.

That's the advice I would impart. There are plenty of resources to show homeowners how to do landscape responsibly. It simply means using the plants that capture the energy from the sun, turn it into food, but then transfer that energy to other organisms. Most of the ornamental plants from Asia don't do that. The energy is just locked up in those plants, as though they're just decorations. But plants are much more than decorations. That's the message I want to get across.

Can insects adapt to alien plants?

In a theoretical sense, the answer is "yes." But in a practical and ecological sense, the answer is "no." Adaptation takes a long, long time. What happens when you take the milkweed out of your yard and put in a Bradford pear? Does the monarch butterfly adapt to the Bradford pear? No, it dies and disappears.

We've changed the landscape so fast. I'll use the monarch as another example. We got rid of all the quote "weeds" in agriculture: the milkweed, the asters that support monarch migration and all the flowering plants that support our native bees. In an ecological blink of the eye, we just eliminated them. So, the monarchs disappeared. There's no adaptation going on; they starve.

An eastern bluebird female flies to her nest with a grasshopper to feed her young. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

Host plant adaptation is rare, and it takes a long time. For example, we brought Phragmites, an invasive genotype of common reed, over from Europe 400 years ago. In Europe, it supports 170 species of insects; they co-evolved with it. Here, after 400 years, it supports only five insect species. So that's how fast adaptation happens.

What conservation efforts and actions have been taken to try to save nature and threatened species and how effective have they been, including our National Parks, the Endangered Species Act, wetlands and waterway protection, and others?

You've named the major ones. They're wonderful, and I'm glad we have them. But we're in the sixth great extinction, so obviously they're not working. What we've tried to do is perpetuate the idea that humans and nature can’t coexist. So we establish parks, and that's where nature (is) confined.

But, parks and preserves are not big enough, and they're not connected enough, so there's a steady drain of species from these "protected areas." In the meantime, outside of parks and preserves, we continue to eliminate nature.

So, we need a new model that does conservation where humans are. We do need those parks and preserves - - they are our species pool - - but they're not enough, as the last 100 years have shown very clearly. They're not working.

U.S. turf is our single largest irrigated crop. It's also led to habitat destruction and fragmentation. What are the various cultural, ecological and evolutionary influences that led to this situation?

Grass turf, in the United States covers 40 million acres -- the size of New England.

It's a status symbol for the rich, and it comes from Europe. The aristocracy were the only people with lawns. They didn't need the land for agriculture; they had plenty of extra land. And they had a lot of labor to maintain their lawns -- serfs, slaves, indentured servants -- and a lot of sheep. All of those things were a sign of wealth.

When we established the colonies, lawn remained an important status symbol. If you could have a lawn--like Thomas Jefferson or George Washington--it showed that you too were well off.

Then, around the turn of the last century, we invented the lawnmower. At first, it was a push lawnmower and then became gas-powered. The lawnmower meant that you didn't need sheep or slaves to have a lawn. So everybody who wanted a lawn could have one.

In the 1950s, after the war, when we invented suburbia, lawn really became a status symbol. You had to have a perfect lawn to show that you were a good member of your neighborhood. And you needed to maintain that status symbol to show you were an important member of a high-class neighborhood.

And then all the lawn products came along and the marketing to use them. When you turned on the TV, you heard that if you have dandelions or clover, you're a bad person. You have to buy fertilizer and herbicide and make sure that you have a golf-course-perfect lawn. Why? All that does is load our water system with pesticides and too much fertilizer.

So our obsession with lawn started with our need to fit in, our need to demonstrate that we are a good member of the tribe. That's not going to change. We'll always have that need. But we need to change what that accepted status symbol is.

That's starting to happen. You can see it, particularly in the West, where there's not enough water for thirsty lawns. So the guy with the big lawn is not the admired guy anymore; he's a pariah because everyone knows that he's wasting precious water. And the guy with the beautiful xeric landscape now has high status.

In the East, we do have enough rain for a lawn, but what I'm suggesting is that we cut the lawn area in half. If we could cut that 40 million acres in half, that would give us 20 million acres that we could put toward conservation. I want that to become the new status symbol.

In Nature’s Best Hope, you wrote that “carrying capacity is the ability of a particular place to support a specific species.” How is that relevant here?

I actually want to change that formal definition. Carrying capacity is the ability of a given place, all the resources in that place, to support all of the species that should be there. Right now what's happening is that the humans are usurping all of the resources. In doing that, we've taken the resources away from almost everything else, and that's why we're seeing species decline everywhere. That means that we are above carrying capacity.

The concept of carrying capacity is important because it's a measure of sustainability. Populations over the carrying capacity are using resources faster than the ecosystem produces them. If you overshoot the carrying capacity, you've got to get the population down so that the resources can accumulate again to support life. If you stay above the carrying capacity, you wipe out the resources and that's the end of that. It's something that people don't like to talk about, because we think we can grow forever on this finite planet without any problems.

How are insects critical to maintaining the diversity of other species?

In 1987, E.O. Wilson wrote a paper called "The Little Things That Run the World." He was talking about what would happen if Planet Earth lost its insects. Several things would happen.

We would lose most of our flowering plants, because insects are the primary pollinators of 90% of our flowering plants. If we lost our flowering plants, it would collapse the food webs. The energy flow through our terrestrial ecosystem, so that the animals that depend on that energy -- the amphibians, the mammals, the reptiles, the birds, and our freshwater fish -- would all disappear.

Jays can carry acorns a mile from the parent tree before tapping below the ground where many will germinate to become new oak trees. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

The Earth would rot, because we would have lost the insect decomposers that rapidly turn over nutrients, and only bacteria and fungi would be left to break things down. It would be a mass of things that were decomposing very slowly.

And humans would not survive any of those drastic changes.

Insects are essential to life as we know it.

What is the concept of a Homegrown National Park, and how can we as concerned homeowners contribute to it?

I came up with that concept when I was contemplating the amount of area that's covered in lawn. It comes to 40 million acres (and that was in 2005; it's probably more now) -- if we cut that area in half, that's 20 million acres we put toward conservation. If everyone cut their area of lawn in half and started planting the plants we were talking about, we could create a new national park.

And since we're doing it at home, let's call it a Homegrown National Park. How big will it be? I started adding up the areas of all the major national parks in the country (Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Tetons, Mt. Rainier, Great Smoky Mountains, etc.) and their combined area was still less than 20 million acres. So, we'll have the biggest national park in the country, called Homegrown National Park.

Homeowners can contribute to that by cutting their lawn in half and putting in the plants that support healthy ecosystems. And we can measure how we're doing in attaining this goal of 20 million acres, by having people go to my website, homegrownnationalpark.org, and putting themselves on the map. You can put in your location and the amount of area you're conserving. It's like those thermometers they use in fundraising drives to measure progress, but we're measuring acres converted.

You can also see who else in your county is doing it and how the national effort is going.

Why are bees important, and how can we support them?

Bees are important because they are the primary pollinators of flowering plants. A lot of insects pollinate, but our native bees, and there are 4,000 species of them, are the ones that are specialized. They don't do it by accident; they do it very efficiently. And they did most of the pollination in North America before we brought the honeybee over.

Honeybees are really good at pollinating a lot of our crops, which are also non-native species. I’m not proposing that we get rid of the honeybee, but we can't lose our native bees because they pollinate the bulk of the plants that are out there. If you don't pollinate the plants, they don't reproduce, and you lose them.

What about caterpillars?

Caterpillars transfer energy from plants to animals. Remember, plants are capturing energy from the sun and turning it into food. That food is stored in the plant parts, mostly leaves. If it stays there, then you don't have any animals, because the animals aren't capturing energy from the sun; they have to get it from plants. Most vertebrates don't eat plants directly -- they eat something else that eats plants, which is typically insects.

It turns out that caterpillars are transferring more energy from plants to other animals than any other type of plant eater. If you develop a landscape that doesn't have a lot of caterpillars, you've got a failed food web.

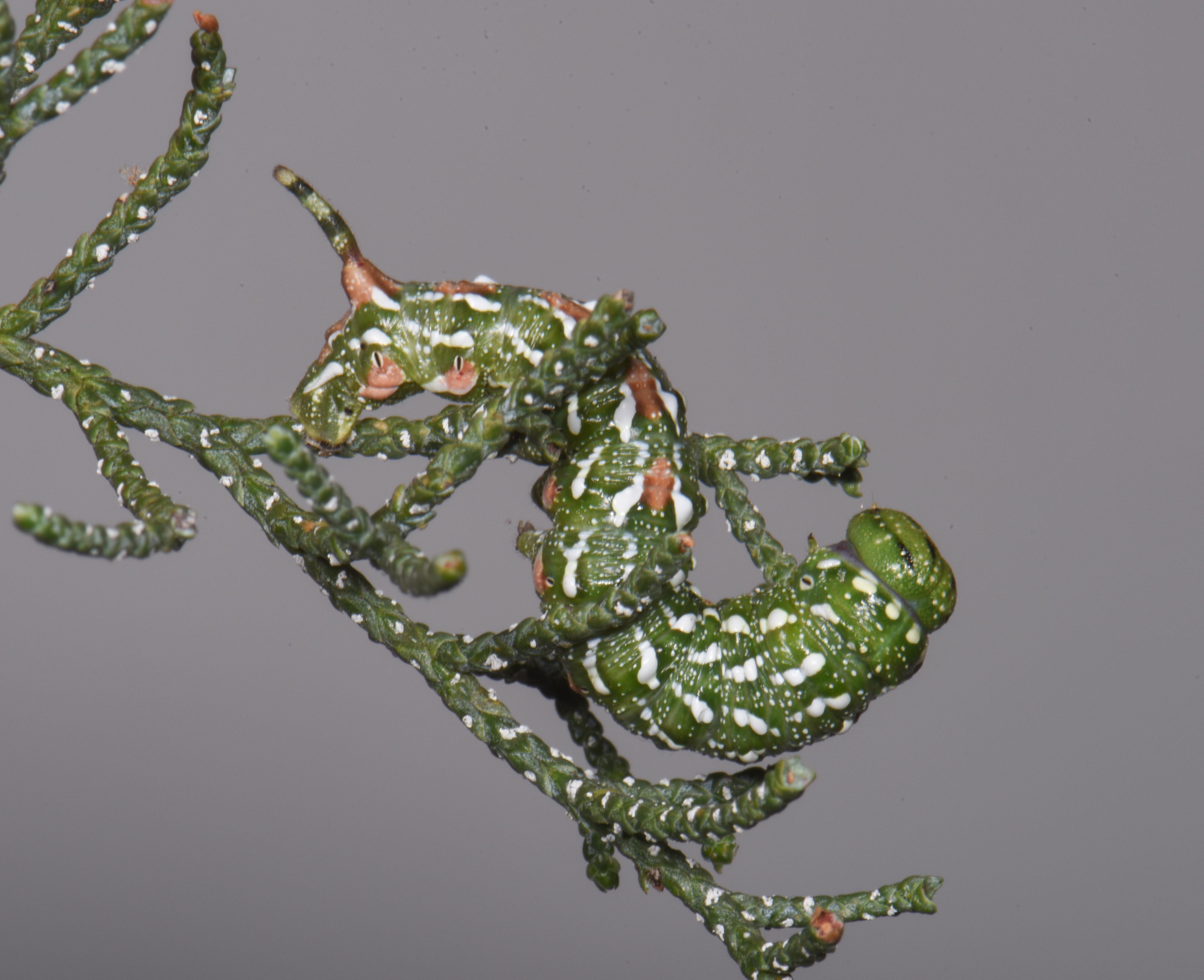

The Doll's sphinx caterpillar blends in perfectly with its juniper host plant. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

Why are there such precipitous declines in the bee and monarch butterfly populations?

Because we've gotten rid of their host plants!

A third of our bees are very specialized. They can only reproduce on the pollen of particular plants. If you take those plants away, they're gone.

The invention of Roundup agriculture products for corn and soybeans, in particular; that's really what has done it. The growers spray their crops, but they also spray the side of the road, and they turn what used to be weedy areas rich in native plant into lawn. If you drive through the Midwest, you see corn, soybeans, and lawn. The native plants that supported our monarchs and all of our bees are gone, giving us thousands of square miles of ecologically barren landscapes.

But, we can fix this! I just saw a video on pollinator strips that they're doing research on in Iowa. It's been a fantastic success. Of course, it makes sense. They're putting these plants back, not just on the side of the road. They're doing it at strategic points in the watershed so that these plantings are intercepting water as it flows across farm fields. Pollinator strips are intercepting topsoil, nutrients, and are creating a lot of habitat for the pollinators, and other things, like birds.

According to the video, the farmers like it and have adopted it. It's a no-brainer solution.

You've written that there are more than 3,300 invasive plant species in the United States alone. Can you talk about their impact on native plants, animals and the overall ecological system?

An invasive plant is a non-native plant that's aggressively displacing native plant communities. We have more than 3,300 species of non-native plants that have been introduced and have escaped into the wild. Not all of them are serious invasives. But many are, like kudzu and some ornamentals that have escaped.

So when you go into a typical natural area and you measure the amount of plant biomass that is native or non-native, right now we're around the one-third mark. That is, about a third of the plants in a natural area are from Asia. These are the plants that are not supporting the food web; they're not supplying that energy from the sun into the food chain. So you've reduced the amount of energy that natural area is producing by one-third, and that's the major issue with invasive plants. They are taking out the native plants that support the food web.

There's an interaction here. It has to do with deer -- white-tailed deer, black-tailed deer and other deer in the West. We have too many deer almost everywhere, and they love the native plants, just like the insects do, and they don't like the non-native plants. When non-natives escape from our gardens into natural areas, the deer don't eat them, but they do eat the natives and pretty soon all you have is the non-natives. That has encouraged invasive species almost everywhere.

There's a two-pronged effect here. You can't talk about controlling invasive plants without talking about controlling deer.

You began Nature’s Best Hope with a chapter on conservation “visionaries.” Why?

I talk about Aldo Leopold and E.O. Wilson. Both of them had dreams and were very concerned about the loss of the natural world.

Leopold dreamt that humans would be able to develop a land ethic and treat the land a little better than we've been treating it. And Wilson had a dream of saving functional ecosystems on half of the planet. If we don't do that, he said, we're going to lose life on all of the planet.

Leopold is dead and didn't get to see his dream come true. Wilson is 92. I started the book with those two dreams, because I believe "we can do this." We can realize Leopold's and Wilson's dreams, and this book explains how we can do it.

It was a way of introducing the fact that we have a big job ahead of us, but it's doable, we can do it!

How do you respond to people who characterize Nature’s Best Hope as controversial?

What part is controversial? Show me the data that say I'm wrong. It's not enough to have an opinion that I'm not right. Show me that I'm not right. Then we can have a discussion about the science that generated the controversial data. I haven't seen any controversial data yet.

What does your home garden look like, and what steps did you take to change its original state?

About 20 years ago, we bought a piece of a very old farm that was broken up. It's 10 acres, and its last use was mowing for hay. When you mow for hay around here, you're really mowing all the invasive species. But that was OK, because they were delivering it to the mushroom industry, which doesn't care what plants were in there. So, when they stopped mowing, it just became a tangle of Asian plants covering the entire 10 acres.

I don't use the word garden, because people picture a confined little space where you have all your fancy plants, and it's beautiful and you spend all your time weeding. I talk about landscapes. Every homeowner owns a landscape, and part of it might be what they think of as their formal garden, but all of it is either contributing or detracting from the local ecosystem.

If you have a wonderful showy garden that's 100-by-100 feet, and you have 2 acres of lawn, then no matter how great your garden is, you are still wrecking your local ecosystem. That’s why I talk about the greater landscape rather than the garden.

On our 10 acres, we got rid of the invasive plants, and I give my wife most of the credit for that. It's a constant battle because the neighbors have not gotten rid of their invasive plants. They reseed all the time, so we have to be vigilant all the time.

Eastern red cedars in Tallamy's front yard. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

But once the bulk of the invasives were gone, we gradually built different parts of an Eastern deciduous biome. We have Eastern deciduous forest, but we also have a meadow, a wetland and scrub habitat; we keep adding plants that were here a long time ago to rebuild those ecosystems.

It's been a wonderfully rewarding exercise, and we're still doing it; but right away, it was so much fun to see all the species that came back as soon as we put in the plants that supported them.

What are some of those?

I'll give you an example. Five years ago, I decided to take a picture of every moth species that I could find on our property. I'm up to 1,091 moth species that I've photographed. They are here because of the plants we put back. That's 40% of all the moth species that occur in all of Pennsylvania, which is 2.4 million acres.

Those moths are bird food, and we now have 60 species of birds that have bred on our property. Habitat is not just a place to live; it's food.

Most birds like this white eyed vireo rear their young primarily on caterpillars. Courtesy of Douglas Tallamy

So, we don't talk about our garden, but our landscape. Our landscape is very productive. I would never offer it as the perfect landscape design -- I'm not a landscape designer, nor is my wife -- but it's a really good restoration.

Most people have smaller acreage to work with, but it's still a good model.

Yes, I talk about that in my book. There's a woman in Chicago who has one-tenth of an acre. She is a landscape designer, and she's done a wonderful job with it. She got rid of her invasive plants and put in 60 species of native plants, and it's beautiful.

But it's only one-tenth of an acre, a third of the size of an average lot in North America. Nevertheless, she's recorded 120 species of birds on her property, because she has what birds need on that one-tenth acre. So it does work on smaller properties.

There's no doubt that the bigger the area you convert, the more productive your property will be. But when I talk to people with small properties, I remind them that their property is attached to another small property. If they're the only one on the planet doing this, it's not going to work. But if their neighbors do it as well, and everybody does it, it's going to work great.

How did you come up with the basic idea of the Homegrown National Park?

It really was the act of moving into this property, this converted farm. By the time we had moved in, all the rootstocks of those invasive plants that had been mowed down grew back. It was a giant tangle of Asian vines and multiflora rose and autumn olive.

And I'm an entomologist, so I'm always looking for insects, and you do that by looking for little areas of leaves that have been eaten. I noticed that these invasive plants didn't have any insects eating them. The native plants supported good insect populations.

That wasn't a surprise to me because we had studied in graduate school how insect herbivores specialize on particular host plants, and of course, native insects could not have specialized on non-native plants; they would only eat native plants. But what was a surprise was that other people weren't thinking about this.

That's what changed the direction of my research. We started to measure what was happening to local food webs as we replace native plants with non-native species, and we're still doing that.

So it was the act of moving to this property and living with a bunch of Asian plants that made me realize that this is a serious, serious problem. People are landscaping with these Asian plants, some of which are invasive, so that got me into this whole area.

I was also surprised when I found that the public cared about this. I started to give talks about it, and the public was interested. People want to be able to do something positive to help the environment, and my message is, you can! You can fix your own property.

It's also enjoyable if you like working outside or even if you just like to look outside.

Yes, it's enjoyable; and if you don't like working with plants, you can hire someone to do it for you. You don't have to be stuck with that ecologically dead landscape that has been the model for the last 100 years.

What is some of the most important research you’ve done to come to your conclusions?

I summarized much of our research in my book Nature's Best Hope, and that's the best place to look for it, there or in scientific articles in journals.

In the beginning, we were just documenting the difference in the ability of native plants to support the food web over non-native plants.

In one recent study, we looked at caterpillars in hedgerows that were either invaded with non-native Asian species or not invaded. And when they were invaded, they reduced the caterpillars the birds depend on by 96%. If you take away the bird feed, you take away the birds too.

We've done a whole bunch of studies. I think the most important thing we have found, other than the obvious that these non-native plants aren't doing the job, is that not all of our native plants are doing the job either -- and this is the concept of keystone species. It turns out that just 5% of our native plants are making 75% of the food that generates our food web. Fourteen percent of our native plants make 90% of that food.

This means that 85 to 86% of our native plants are contributing, but not all that much. So it's not a black and white "native-good" versus "non-native-bad." I could build a 100% native landscape that supports almost no animals.

I think our biggest contribution is to rank plants in terms of their contribution to the food web, and we have that information for every county in the country. And next we want to do it for every country in the world! This is a problem worldwide.

Look at the use of the eucalyptus as a shade tree for coffee around the world. In Portugal, eucalyptus from Australia is the most common tree in the forest! Outside of Australia, this plant supports almost nothing.

So this is our message for restoration ecologists, homeowners and AG people everywhere: You have to use the right plants, or you're going to lose the biodiversity. The World Wildlife Fund says that we've lost two thirds of our wildlife in the last 50 years since 1970. We can turn that around by putting the right plants back.

We lost those species by taking away the plants that support them. We call it habitat loss, and it is, but it doesn't have to be. We can have productive native plants in our cities, on the edges of our agriculture, in our yards, on our roadsides, in our corporate landscapes -- there's no reason why we can't be using those plants. So that's the message I want to send everywhere.

That's a big job.

Yes, it's a big job. It's going to take me until the end!

But you can measure your progress on our website, where you can see county by county what's happening.

Find out more about Tallamy and his initiatives at homegrownnationalpark.org.