Chandra Wright moved to Gulf Shores, Alabama in 2008 to spend more time scuba diving and achieve a better work-life balance while practicing as an attorney.

Two years later, on April 20, 2010, life changed for Wright and everyone in the Gulf Shores region when the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded offshore. During an 87-day period more than 134 million gallons of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico making the Deepwater Horizon disaster the largest and most destructive oil spill in marine drilling history.

“The day that happened, I came to the beach at Gulf State Park to witness it first hand. You could smell the oil, you could smell the petroleum, and I cried. It still chokes me up when I think about that,” said Wright as her inflection paused intermittently to hold back tears even 14 years later. “I could not come back to the beach until it was over, and I wasn't sure if I was ever going to be able to dive in the Gulf of Mexico again.”

The spill did far more than just shatter dreams. Eleven workers died, and more than 770 square miles of mesophotic and deep-sea habitats were negatively impacted according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Gulf Shores-Orange Beach community in coastal Alabama that relies on tourism became a ghost-town.

Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion. (Photo: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

No one could prepare for the ongoing impact to the area’s marine environment, wildlife and habitats or begin to perceive what kind of permanent damage was done. The disaster put a spotlight on the environmental vulnerability of the Gulf Shores coastline and the trickle-down effect on a destination that receives more than six-million visitors a year.

“It was a pretty significant realization that if we don't take care of this environment, then what are we going to do? We don't have those visitors. We don't have the income. Our businesses are going to have to close. We have to educate folks that if we don't take care of it, then we're at risk of losing it,” said Wright.

For months after the spill the visual impacts of the disaster were hard to escape like workers in hazmat suits cleaning up oil on the beaches; pelicans covered in black oil; suffocated turtles found dead on the shores; seabirds unable to fly from oil-soaked wings and stranded dolphins with devastated immune systems becoming part of the largest die-off of the species ever recorded in the Gulf of Mexico’s northern waters.

Oil spreads across the water following the rig explosion. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

While the future looked grim for the natural resources and wildlife along the Gulf Coast, the Deepwater Horizon Restoration funds that were earmarked for the recovery projects became the silver lining of the world’s most disastrous ocean oil spill. These projects are the unexpected positive outcomes that raise the bar for innovative restoration, protecting fragile habitats and educational initiatives about the fragility of nature.

To date Alabama has more than 170 projects completed, underway or approved with a cost estimated at more than $1.1 billion putting the Gulf Shores on a more solid environmental footing for the future.

The Lodge at Gulf State Park. (Photo: The Lodge at Gulf State Park)

The Lodge at Gulf State Park

The Lodge at Gulf State Park was one of the largest projects to receive funding in the state of Alabama. The $135 million it received from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and state funding resulted in new life to a complex that has always been a community centerpiece.

Residents like Wright who were personally impacted by the oil spill were compelled to become an active part of the environmental path forward in Gulf Shores, so she traded in her legal work for a higher calling.

“That was my personal wake-up call. People ask me all the time if I am a marine biologist. And I'm like, no, I'm a recovering attorney that used to do a lot of divorce work,” said Wright who is now the director of environmental and educational initiatives for The Lodge at Gulf State Park.

The oil spill funds were used for construction of the lodge that was built in 1974 and destroyed by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. They were also used to fund five enhancement projects making The Lodge at Gulf State Park one of the most environmentally friendly resorts in the world.

These projects included a re-build of the park’s Learning Campus, dune restoration and enhancements to the park’s 28-miles of trails. Every decision made was done with a mission to make the lodge an international benchmark for environmental and economic sustainability while demonstrating best practices for outdoor recreation, education, and hospitality.

The Hilton Hotel built on the site recycled up to 75% of the construction waste. Implementing responsible water sourcing enables the lodge to use condensation from the HVAC system to replace water in the pool.

Some of the more visible environmental efforts include adding bulk soap dispensers in rooms and dining menus featuring locally sourced food with a Zero Single Serve initiative. Wright says these are evolving efforts that require regular evaluation to maintain the highest possible environmental stewardship.

“The best product today may not be the best product tomorrow, so we're constantly looking for those kinds of things. We try to be that leading voice in the hospitality industry by committing to do things the right way," said Wright.

The lodge’s environmental footprint is 1/3 less than the original lodge and located more than 200-feet further back from the Gulf. Three-quarters of its landscaping uses native species that help restore the coastal landscape resulting in new habitats for nesting sea turtles and native birds.

Gulf State Park Interpretive Center. (Photo by Anietra Hamper)

Two of the most important enhancement projects at the lodge are the Learning Campus and Interpretive Center. These centers offer immersive programs for residents and visitors to learn how they can play a role in protecting the local natural resources.The Interpretive Center is one of the most popular spots at the park with regular programs, activities, and experiences utilizing the park’s 6,150 acres that spans nine ecosystems. It is Alabama’s most environmentally friendly building set among some of the state’s most abundant diversity of flora and fauna. It includes a public beach pavilion, an angler academy for fishing on the pier, bike rentals, and birding.

“It's so much fun when you're educating everybody from the littlest of the kids to their grandparents and great-grandparents. And it's like you see all these light bulbs go on, and people go, oh, that's so cool. Now I want to get involved,” said Wright.

The Interpretive Center at Gulf State Park generates its own drinking water. (Photo by Anietra Hamper)

The facility itself is a living example of sustainability. A water treatment system filters collected rainwater turning it into potable drinking water and 51 solar panels enables the center to produce its own electricity. Most impressively the park’s Learning Campus is one of only 30 facilities in the world to have the Living Building Challenge certification meaning its constructed to the highest sustainability standards.

The lodge is making the oil spill proceeds work for it now and allocating money into savings to sustain programs and maintenance going forward.

Students at the Gulf Coast Center for Eco-tourism and Sustainability camp. (Photo by Travis Langen)

Gulf Coast Center for Eco-tourism and Sustainability

Another notable phoenix that rose from the ashes due to the funding from the oil spill was the non-profit Gulf Coast Center for Eco-tourism and Sustainability.

“There was a big a-ha moment that took place that the quality of our life is directly tied to the health of our environment. It's not just the economy. It's not just the tourism dollars. It's a state of well-being. It's a sense of identity and what happens when you start to lose that, or that starts to unravel,” said Travis Langen, executive director of the Gulf Coast Center for Eco-tourism, and Sustainability.

Langen arrived at Gulf Shores eight years after the oil spill.

“It was really this overwhelming sense of doom, like this is our new normal. Our new future is just a completely spoiled environment with no end in sight,” said Langen.

The Gulf Coast Center for Eco-tourism and Sustainability was a project designed to change that outlook by giving people hope and building on the environmental work that was already underway by many organizations before the spill.

The center’s innovative programs connect people to the natural world through scientific and experiential knowledge gained from hands-on immersion. The multi-disciplinary programs rely on a myriad of community entities like the park system, the schools, tourism, and local municipalities.

An arts and crafts project exploring tie dye with natural color. (Photo by Travis Langen)

Some of the popular programs are candle-making and textile dying made from natural resources, so participants walk away with more than just an arts project to take home. These experiences tie in lessons in local history, chemistry, botany, and ecology too.

And, then there’s the sun ovens that are a popular activity for kids.

“You can cook a batch of chocolate chip cookies in 10 minutes, so we bring that down to the beach with us. The kids are swimming, and then they go and check on the sun ovens to see how the cookies are coming along using the free energy from the sun,” said Langen.

A growing part of the center’s programs involve service-learning and voluntourism activities like composting and reducing the environmental footprint. These programs are a way for visitors to the area to take home a bit more than just gift shop souvenirs and instead learn how to make a lasting environmental difference.

“We hope you take whatever inspiration you have gained from these experiences and take them home to start rolling up your sleeves and bettering your own community,” said Langen.

Future expansion at the center’s campus will include a farm and a tree nursery to grow saplings earmarked for restoration efforts.

Langen is encouraged by the direct impact of the center’s programs that he sees on the people who enjoy them. It’s an inspiring outlook on the region’s environmental future that was hard for locals to envision just a few years ago.

Gulf Shores recovery and cleanup assessments. (Photo: Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources)

The Long-Term Recovery

While no one can predict the long-term impact of the oil spill, millions of dollars in funding are allocated to ongoing monitoring of affected marine life and habitats and even fostering new research techniques in the process.

The most recent State of Alabama Deepwater Horizon Restoration Progress Report (2022) shows recovery progress moving in the right direction.

“Nature is good at healing and recovering from impacts. I have seen great progress on many fronts,” said Chris Blankenship, commissioner of Alabama’s Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

An oyster restoration project underway in Gulf Shores. (Photo: Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources)

One effort showing progress is oyster restoration that is essential to Alabama’s coastal economy and important to the local ecosystem. The oil spill caused unprecedented damage to the Gulf Coast’s oyster resources with the loss of 8.3 million adult oysters. Oyster gardening has helped to reestablish populations on existing reef sites.

While this is encouraging news, some recovery efforts will take longer than others.

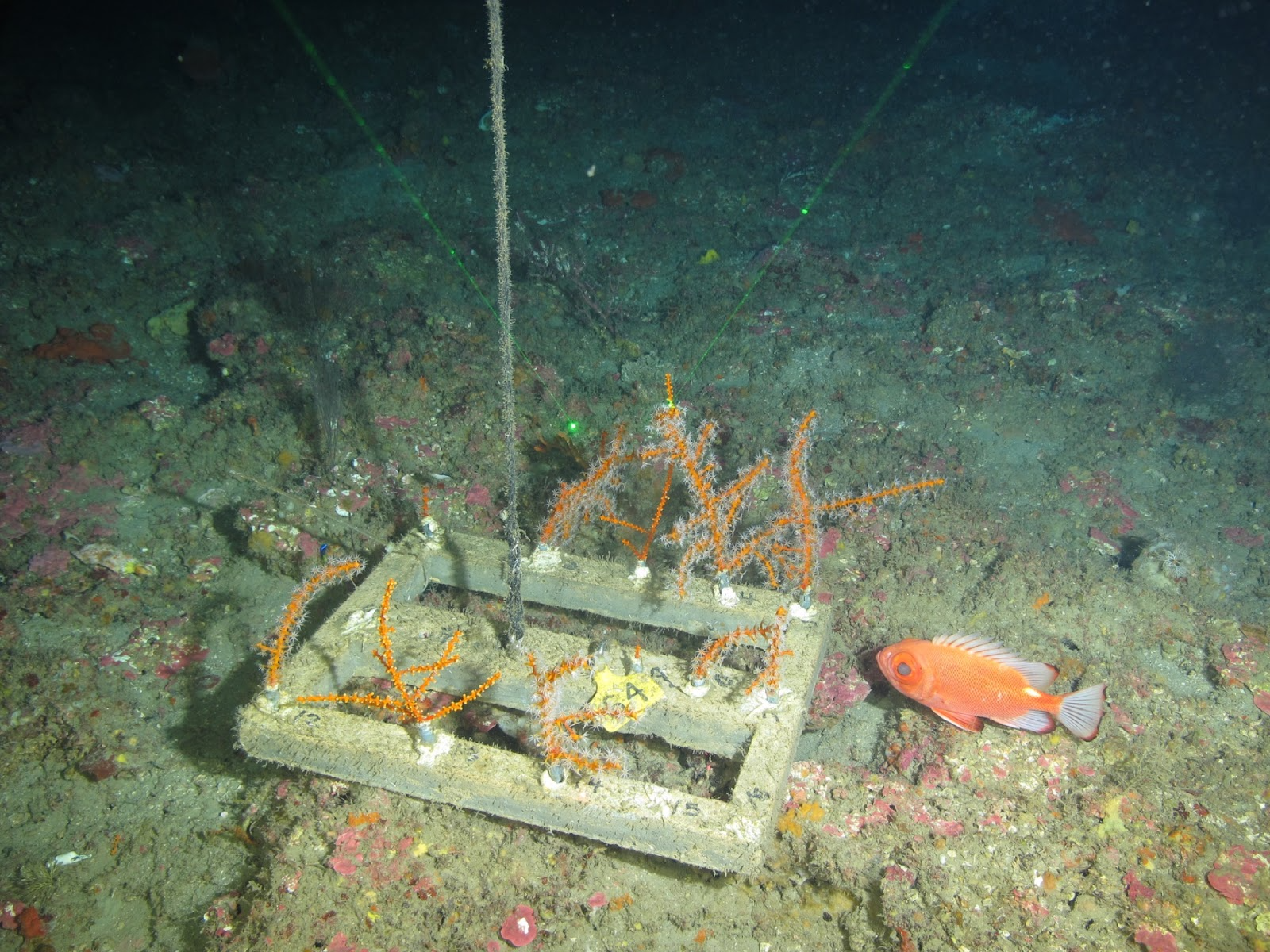

“The deep-water corals may take longer to recover than some habitats because they are slow growing. We are working with the other Gulf States and the federal trustees to recover different species in multiple habitats,” said Blankenship.

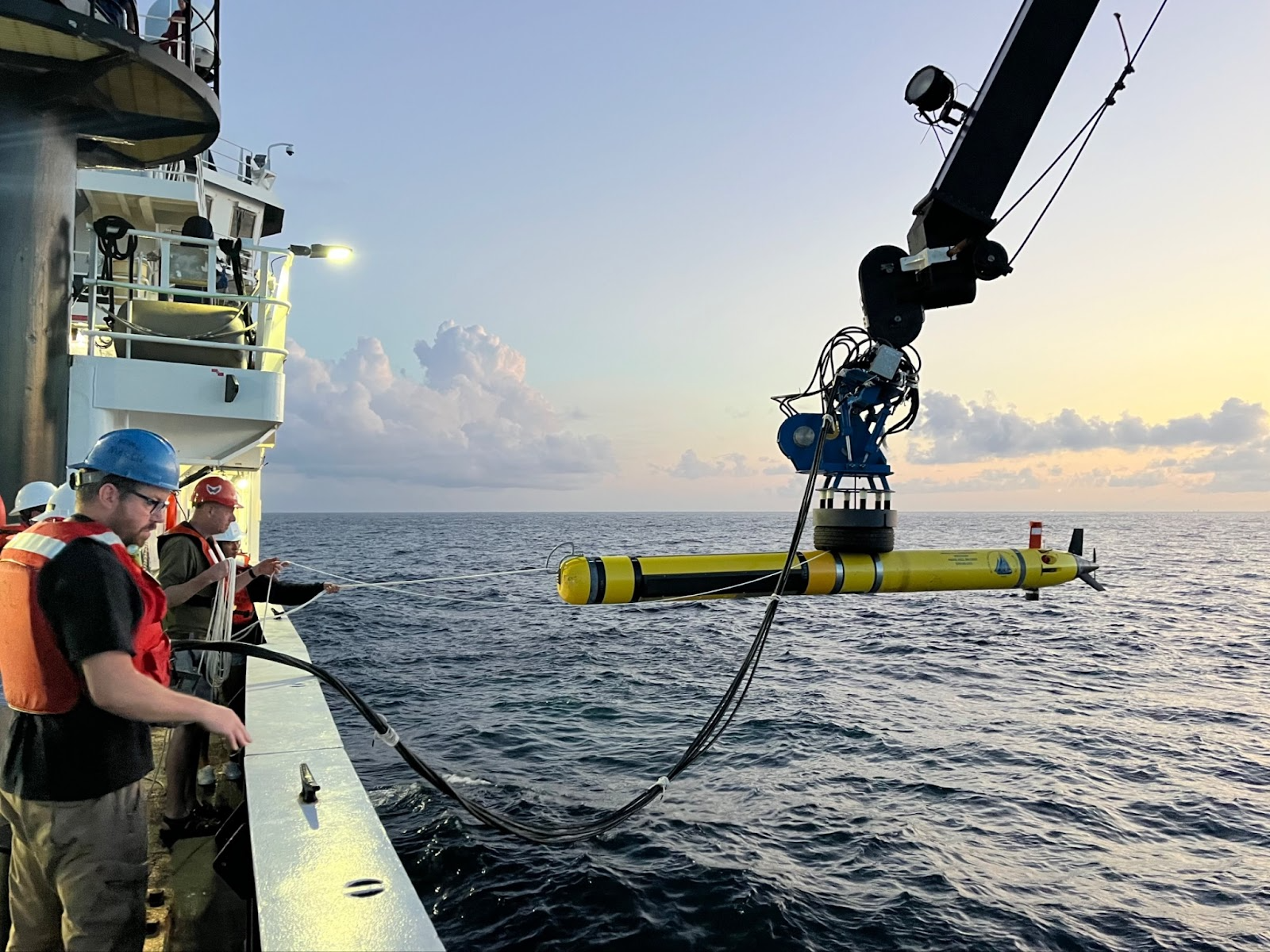

Mesophotic and Deep Benthic Communities restoration experts and AUV technicians lower the WHOI Remus 600 into the water to map the seafloor. (Photo by Claire Huang, NOAA NCCOS)

Sea floor mapping is one way scientists are monitoring the progress of deep-sea corals.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and U.S. Geological Survey conducts expeditions to study the deep-water habitats and ecosystems of more than 3,100 square miles around the spill site. The latest expedition in 2023 included the use of new tools like a deep-sea coral elevator and first-of-its-kind seafloor trials to restore coral deep-water communities 230 feet below the surface.

These expeditions, while necessary for the monitoring of damage from the oil spill, have opened new frontiers for studying, and restoring some of the world’s deepest, and until now, inaccessible ocean habitats.

Transplanted corals grow on an outplanting rack placed on the seafloor to help restore mesophotic habitats injured by the oil spill. (Photo: NOAA, UNCW UVP, National Marine Sanctuary Foundation)

Other restoration efforts underway include land acquisitions and establishing new artificial reefs off Alabama’s coast. All these efforts are working in concert to not only restore environments and habitats destroyed by the oil spill but to make them stronger to better withstand any future environmental catastrophes.

These projects give hope to residents like Wright. While she still endures the emotional scars, she’s been able to return to the Gulf waters to dive again.

Anietra Hamper is an award-winning outdoor writer, author and lifelong angler who specializes in outdoor adventure and fishing for some of the largest species around the world. Having spent a career as a top-rated television news anchor and investigative reporter, Anietra brings credibility to the stories she covers with her "boots-on-the-ground" journalistic approach. Anietra is based in Gahanna, Ohio.