Adrain Pinder has always been fascinated by fish, especially the large and unusual species that easily catch angler’s attention in photos.

“When I was young, I’d see pictures in the angling press and occasionally there would be someone with a gigantic, ridiculous looking fish. These fish blew me away and I thought one day I’d like to go and catch one,” said Dr. Adrian Pinder, director of Bournemouth University Global Environmental Solutions and chair of the Mahseer Trust.

The fish in the photo that caught Pinder’s fascination is the hump-backed mahseer. It is one of the world’s largest freshwater fish that is only found in the River Cauvery and its tributaries in southern India. As a lifelong angler and scientist having studied invasive species, salmon migration and other fisheries research, one of Pinder’s greatest contributions to species conservation started by chance while chasing that childhood attraction to the hump-backed mahseer.

In 2010 Pinder traveled to south India as a recreational angler but what he discovered when he got there was far more than a checked box for a bucket-list dream.

Instead, he stumbled on what would lead him on a multi-decade journey revealing the startling reality that this prized trophy fish-of-a-lifetime was quietly slipping into extinction with no one noticing.

“It was purely based on the fact that nobody was able to tell me what species these fish were that I was catching, and it made me realize that there’s an awful lot of work that needs to be done on these fish, and maybe I could weave that into my day job,” said Pinder.

The reason no one knew the species in the river is because the fish had no scientific name at the time. Many species of the mahseer were generically referred to in India as “Tiger of the River,” a name adopted by natives as the only way to identify these freshwater giants.

With no scientific name attached to the species that meant there were no protections for it, nor was anyone studying them to see if any were needed. Unnamed species are not uncommon for biodiversity hotspots around the world including the Western Ghats. In the most recent Shoal New Species Report (2022), more than 200 new freshwater species were identified in a single year highlighting the prevalence of species that still exist without scientific names.

It turns out that this species, now recognized as the hump-backed mahseer (Tor remadevii) were being threatened by an invasive species, the blue-fin mahseer (Tor khudree), pushing them into extinction completely unnoticed.

What started out for Pinder as simple angler curiosity ignited his attention as a scientist staring him on a trajectory to save a species that no one knew needed protection.

Invasive species, overfishing, poaching, dams, sand mining and water quality issues are just some of the threats to native fish species around the world. These threats occur in every type of aquatic environment from the remote waters in India to the Atlantic Ocean to pristine rivers and streams in the United States.

This scenario highlights just one example of how anglers around the world play a critical role as citizen scientists on the front lines of species conservation.

Dr. Adrian Pinder releasing a blue-fin mahseer. Photo by Adrian Pinder

Knowledge is power

In places like India with little government oversight and no fisheries management programs, a lack of baseline data means there’s no one keeping check on current species, let alone the threats they face.

“In a country with 1.4 billion people, government level fisheries management in India is predominantly focused on food security (for example, breeding fast growing fish, largely non-native species) for stocking into the country's rivers and reservoirs. Obviously, this in itself is a major threat to the nation's aquatic biodiversity. Even if resources were allocated to monitoring wild fish populations, large monsoonal rivers pose many challenges for robust data collection,” said Pinder.

With species conservation a low priority in India, Pinder was denied permission to conduct scientific studies on the River Cauvery to determine the species of fish in the river.

No official data existed on what is now known as the hump-backed mahseer, so Pinder turned to the only thing that did exist - scribbled records of daily catches from the fishing camp where he stayed. He spent 15 years (1998-2012), manually translating the penned fishing camp records onto a spreadsheet with categories of number of fish caught, weight, descriptions, and other notations to collect the only set of data he could eventually analyze.

“What that data set showed us was the numbers of mahseer in that time was growing rapidly but the mean size of those fish had decreased,” said Pinder.

It wasn’t until Pinder compared angler photographs to those numbers over the same period that his most startling discovery came to light.

Anglers and a guide with a large hump-backed mahseer from the middle reaches of South India's River Cauvery. Photo by J. Bailey

Pinder noticed that all the fish in catch photos up to the early 1990s had gold fins, now identified as the hump-backed mahseer. Most of the fish in photos from 1993 onward had blue fins.

“We didn’t know they were different species at the time,” said Pinder. “We separated out these two groups and what we saw was a massive crash in 2005 of the orange fins and during the same time, an explosion of blue fins.”

How did they get there? Pinder discovered that blue-fin mahseer were intentionally (and repeatedly) stocked into the Cauvery from the mid 1970's originating from the Tata Power hatchery at Lonavla, Maharashtra, and from a dedicated hatchery established in the Upper Cauvery. The blue-fin mahseer’s natural distribution in the River Krishna system is a long way north of the Cauvery but monsoonal floods enabled them to enter other waterways.

The combined data and photos showed that in 1998 the population ratio was one hump-backed mahseer to every four blue-fins, and by 2012 the ratio was one for every 218 blue-fins. These findings showed a 90-percent reduction in population of hump-backed mahseer in most of the main river Cauvery where they were rapidly tumbling into extinction.

“When we realized that the hump-backed had crashed and the blue-fin went up we still didn’t know what species they were,” said Pinder. “Even though this is one of the biggest freshwater fish in the world it had somehow avoided being given a scientific name. We knew it was in big danger of extinction but until that fish had a scientific name it had no conservation status.”

Adrian Pinder and Steve Lockett of the Mahseer Trust. Photo by Steve Lockett

Angler activism

Pinder’s research was instrumental in finally establishing a scientific name for the hump-backed mahseer, the Tor remadevii. It is one of 16 species of genus Tor mahseer.

Because of these efforts, the world’s largest mahseer species is now recognized as ‘Critically Endangered’ on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) global Red List of Threatened Species. With a scientific name and an official conservation status there is now a multi-agency effort to prevent the extinction of the hump-backed mahseer that is believed to only have a couple of breeding populations left.

Adrian Pinder (right) investigates Tor khudree with locals. Photo by Steve Lockett

One of those agencies is the Mahseer Trust that was established in 2008 putting scientific research into conservation practice. The UK registered charity, run by a small group of passionate volunteers, is active in efforts related to river habitat, increasing scientific knowledge for policy level decision-making, helping establish best practices for destination anglers and natives, and generating awareness of the species through workshops for tribal anglers, school children and governments.

“If it hadn’t been for the recreational anglers keeping records over an extended period of time, we would’ve had no data and we would’ve had no baseline to work from,” said Pinder. “We wouldn’t have been able to plot those trends that were happening. Without that, the hump-backed mahseer still would not have a scientific name and it would slip into extinction.”

The work continues to protect the hump-backed mahseer with a vision to eventually set up protected areas and get conservation grants to implement projects like paying locals to guard the river. Unfortunately, since 2012 a ban on fishing in the River Cauvery has prevented any further research for now. What does continue are efforts for global awareness like Pinder’s children’s book called Tiger of the River (Harper Collins, 2022) exposing the plight of the hump-backed mahseer and river conservation.

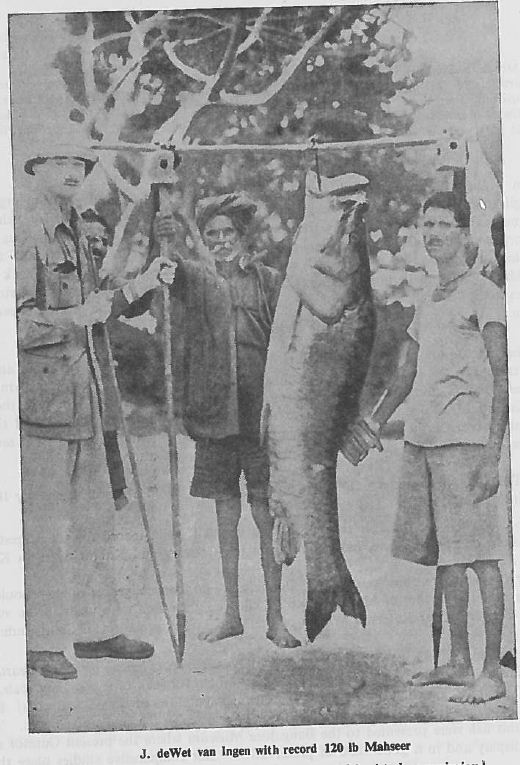

The largest hump-backed mahseer ever verified. A fish of 120lb captured by J. de Wet Van Ingen from the Kabini River in 1946. Photo by Joubert Van Ingen

Tourism impact on poaching

While many fish species are threatened by factors like water quality issues or habitat destruction, some are victims of poaching at the hands of humans. Many poaching scenarios play out in remote villages in places like India and Nepal that have prized fish species in their waters but where personal survival takes precedence over conservation. It is another threat to fish species that Dr. Adrian Pinder witnessed during his time in India.

Recreational destination angling offers natives an alternative, especially when their waters hold prized game species that anglers are willing to travel for to catch.

“You have an opportunity for traveling anglers to input substantial sums of money into locally impoverished villages,” said Adrian Pinder. “When there is an interest from abroad for catching fish and releasing fish the locals realize they can make a lot of money by taking anglers fishing. The fish go back which means the next week they can guide another tourist. All of a sudden, the fish represent the livelihoods of the locals.”

The destination angling concept is a win for everyone: anglers can travel to catch brag-worthy species; depleted fish populations can remain in-tact and have a chance to reproduce and the locals have employment at fishing camps that need guides, bait makers, drivers, cleaners, and catering teams.

“Whole villages are now relying on the recreational anglers coming in. If anything happens to those fish the recreational anglers stop coming, so those villagers start protecting the river, quite literally with their lives,” said Pinder.

Atlantic bluefin tuna caught off the coast of Ireland and tagged as part of the Tuna CHART program. Photo provided by Adrian Molloy

Overfishing and data collection

While it might seem like an oxymoron, anglers play a critical role when it comes to targeting the issue of overfishing. Recent efforts to help protect the Atlantic bluefin tuna off the northern coast of Ireland is proof-positive of how anglers are a part of the conservation solution.

The Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), is the largest, fastest, and most powerful fish in the world making it a sought-after species for premium sushi that can fetch hundreds to thousands of dollars a pound in Japanese fish markets. These factors are what make the bluefin tuna one of the most overfished species in Atlantic waters wreaking havoc on its population numbers.

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) that is responsible for the management and conservation of tuna and tuna-like species in the Atlantic Ocean gave permission for Ireland to collect scientific data on bluefin tuna. This opened the door to establish the Tuna CHART (CatcH And Release Tagging) program, a recreational angling catch-and-release fishery for the purposes of data collection.

Vessel participating in the Tuna CHART program in Atlantic waters. Photo by Ryan Murray

The Tuna CHART program is managed by Inland Fisheries Ireland and the Marine Institute in partnership with several other agencies. It recruits and authorizes about 20 vetted and specially trained professional charter skippers in Ireland each year to participate in a managed tuna tagging program.

What started as a pilot program in Ireland in 2019 has become one of the industry’s greatest assets when it comes to tracking populations of bluefin tuna that return to the coast each year.

“This fish-oriented approach is paramount and ensures release of a healthy fish while providing a high quality, exciting angling experience for the angler with these leviathans of the sea,” said Dr. William Roche, Senior Research Officer at Inland Fisheries Ireland (IFI). “The Tuna CHART program could not deliver without the expert knowledge of the skippers or the enthusiasm and passion of the angler.”

Visiting anglers who hire the skippers for a chance to fish for the Atlantic bluefin tuna become an important part of the data collection process.

“Angling (and anglers) are a key part of the success of this program as this is the only effective way of ‘sampling’ these fish efficiently and ensuring that the measured, tagged and released fish is in the best possible condition. When hooked up, the charter skipper works closely with the angler to ‘manage’ the fish alongside the boat where all of the data recording activity takes place,” said Dr. Roche.

Skippers collecting data measurements on an Atlantic bluefin tuna caught by a recreational angler. Photo by Anietra Hamper

This program is a rare opportunity for recreational anglers to fish for this top ocean predator and become citizen scientists to help monitor and protect the tuna populations.

“The buzz of the hook up, leading to bringing the fish alongside for measuring and tagging underpins this scientific program, and also satisfies the angler’s pursuit of this bucket list species,” said Dr. Roche.

During the first three years of the Tuna CHART program more than 1,500 Atlantic bluefin tuna were caught, tagged, measured, and released in Atlantic waters off the Irish coast. While no specific target numbers are set for the program, just seeing that the Atlantic bluefin tuna populations are returning to the coastal waters year over year shows success.

“Bluefin tuna became a hot topic for anglers in Ireland from the early 2000s when they were first seen off the Donegal coast. In the mid-2000s they all but disappeared, but they have returned in numbers now around the Atlantic Sea coastline from Donegal to Wexford,” said Dr. Willie Roche.

Atlantic bluefin tuna alongside the boat for data collection before release. Photo by Anietra Hamper

The collection of data is helping push the bluefin population numbers and monitoring efforts in the right direction. The most recent Atlantic bluefin tuna status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is listed as “Least Concern” meaning the bluefin is now out of the most concerning conservation category.

The tagging program is slated to continue for the foreseeable future in hopes of maintaining and improving recorded population numbers.

Spawning Yellowstone Cutthroat trout. Photo by NPS/Jacob. W. Frank

Invasive species

Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in the United States established in 1872, is one of the most iconic fishing destinations in the nation due in part to its native cutthroat trout that anglers come to experience. Native species like cutthroat trout and Arctic grayling face threats from non-native rainbow, brook, and brown trout. But the most concerning threat is to the cutthroat trout from the especially destructive and invasive lake trout.

For the last 27 years the Yellowstone National Park Native Fish Conservation Program has made strides to reduce the lake trout populations while protecting cutthroat populations that were on the brink of extinction.

Yellowstone fly fishing volunteers. Photo provided by National Park Service

To stay on top of managing invasive species in Yellowstone’s waters, park biologists employ several methods. Gillnetting has proved effective in removing more than 4.4 million lake trout. Another critical component to the conservation program involves a volunteer fly-fishing program that enlists anglers to help monitor fish species populations.

“We use anglers as one tool for native fish conservation in the park because they’re out there working in waters across the park that we as biologists cannot get to all these places every year. When you bring in groups of anglers that you can direct toward the places where we need assistance for research, we can learn a lot by harnessing the energy of all of those people,” said Todd Koel, leader of the Yellowstone National Park Native Fish Conservation Program.

The fly-fishing volunteer program recruits approximately 50 anglers each year to work with a park coordinator to fish in specifically identified waterways between July and early September. Volunteers aid in catching the fish, collecting data, tagging and fin clipping for genetic sample analysis. This broad-based data collection goes a long way to monitor species populations in the thousands of miles of waterways that flow throughout the park.

The program not only aids biologists with data they might not otherwise be able to collect, but the anglers walk away with something too.“People come to the park for decades and have been fishing here and this is a way for them to give back. They feel like they can help with fish conservation projects and know they are helping us in Yellowstone as biologists achieve goals for our fisheries plus, they get insight into fisheries programs,” said Koel.

Yellowstone National Park relies on anglers throughout the year in other ways too by implementing fishing regulations that are helpful to native species and asking anglers to call in catches of tagged fish for population monitoring.

Though it appears these efforts are tipping the odds in favor of saving the native species, park biologists recognize that it is important to keep the pressure on invasive species and anglers will remain a part of that effort going forward.

Angler ready to release a hump-backed mahseer. Photo by J.Bailey

Increasing the conservation role of anglers

When Dr. Adrian Pinder reflects on his work with the hump-backed mahseer, he pauses when asked how he feels now when looking at those same photos of the fish that fascinated him as a child.

“Mixed emotions. Sadness but also from a personal perspective, pride that I was able to do the research that I could bring that fish [hump-backed mahseer] the attention it was worthy of and get it red listed and now have groups trying to conserve it. I’m proud of that but at the same time it's saddening to know that it’s not looked after in the same way - the giant fish that the Cauvery was famous for,” said Pinder.

These examples are proof positive of the interconnectedness between anglers and their influence on species conservation. They are the boots-on-the-ground, eyes and ears to aid in data collection and they are the most passionate advocates for species’ protection. Just getting on the water to fish, no matter where it is in the world, has a greater impact beyond the joy of just catching a personal best.