A collaborative program from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is turning volunteers into citizen-scientists. Snapshot Wisconsin is a statewide wildlife monitoring program that collects data from an extensive network of volunteer-managed trail cameras. The images are then made available online for cataloguing by volunteers worldwide.

Since Snapshot Wisconsin’s inception millions of detections of wildlife have been captured, resulting in a dataset that has been used to inform population statistics, wildlife management decisions, and is now beginning to fuel new research—such as how human disturbance may be affecting the spatiotemporal relationship of species.

Additionally, anyone can interact with this data online to gain insight into species’ presence and activity statewide.

In a recent interview, Dr. Jennifer Stenglein, a research scientist with the Wisconsin DNR, sat down with Kinute to discuss the Snapshot Wisconsin program and the potential that the amassed data holds for future scientific study of wildlife within the state, and beyond.

Two white deer captured on a Snapshot Wisconsin trail camera | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

Q: Snapshot Wisconsin is a volunteer program that describes itself as “A partnership to monitor wildlife year-round using a statewide network of trail cameras” with the goal of providing the necessary data for wildlife management decisions. Can you describe how the garnered data informs wildlife management decisions?

A: Snapshot Wisconsin data comes from about 2,000 trail cameras monitored by volunteers. Those cameras are collecting photographs year-round and all throughout the state at every one of those locations. Those photos are then classified. The classification is to tell us what animals are in those photos, and sometimes characteristics of those animals—if it's an antlered buck, for instance, or a doe or a fawn, and the number of each individual in the photo. It's the classifications of the photos that we can turn into decision support products. One example of that is fawn to doe ratios. It tells us how productive the deer population is, and that measure of productivity changes across the state.

Doe and fawn | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

Does that data inform harvest decisions?

Yes, harvest decisions are a big one, and it informs the status of the population each year too. It also often plays into the population modeling that we do, and that information is looked at by a committee of folks that make the decisions around here. Some of it is harvest decisions and structure of the harvest season.

For some of the rare species in Wisconsin, we can get decision support information. If we get a detection of a rare species that gives us a lot of info that there was a rare species at a certain place in time. We get that information for moose … whooping crane … martin.

An elusive bobcat | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

Prior to Snapshot, what methods were used to track species population?

Those other approaches are still being used, Snapshot is used in conjunction with them. A lot of surveys are done by wildlife management staff across the state. They will go out and collect observational data for different species. Using the example of deer again, wildlife managers in different counties of Wisconsin will go out, and as they're going about their regular duties they'll record their observations of deer, and those observations are often only during daytime hours. We've discovered that Snapshot Wisconsin provides a way to have a lot more continuous coverage instead of just during the work day. Even though we still have those other ways, mostly observational surveys, having these points in space—these trail cameras—that are observing continuously around the clock and not requiring people to be there to do it is quite an improvement.

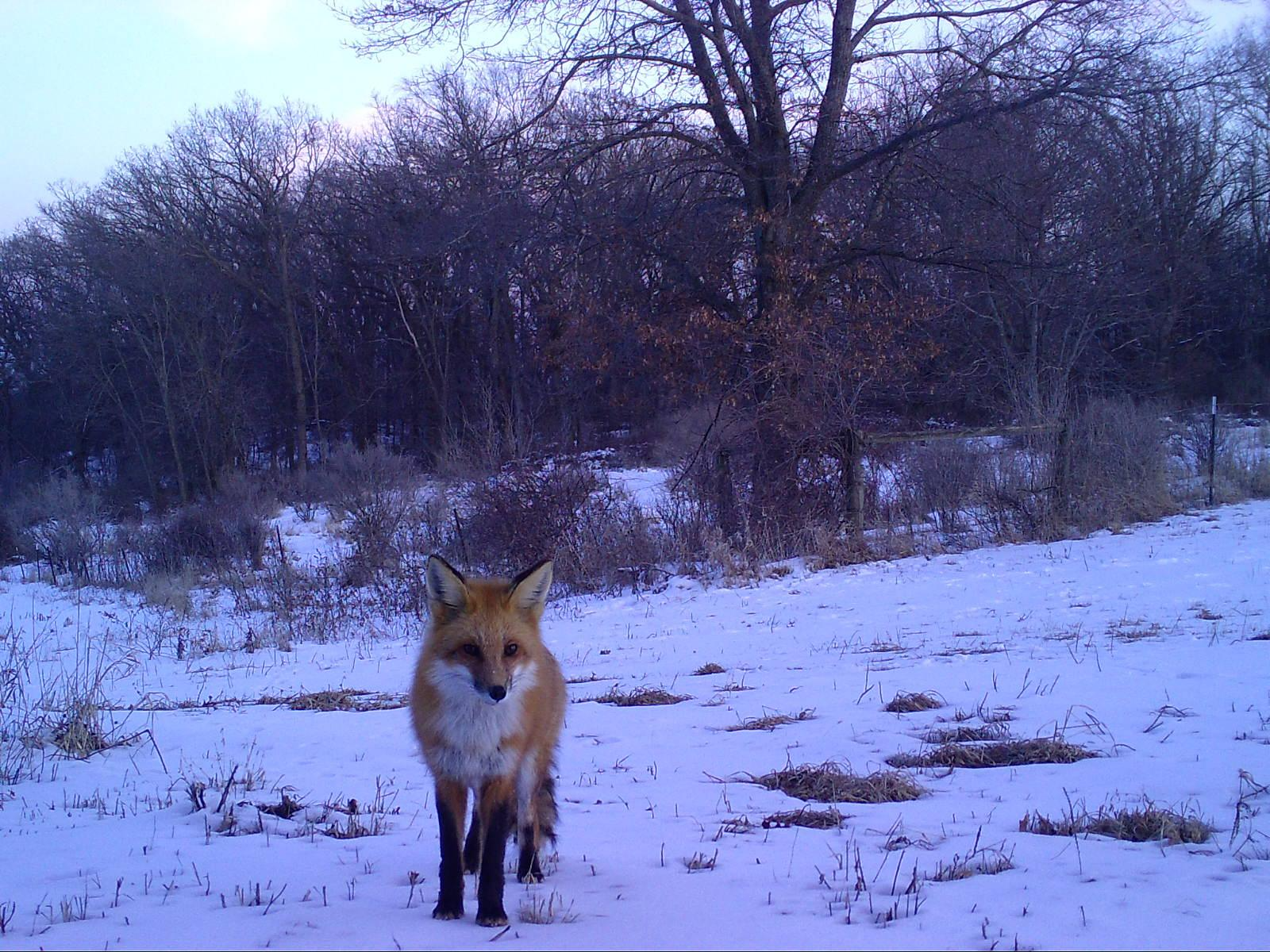

A red fox says hello | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

How are the cameras distributed throughout the state?

We set up a grid of 6,000 survey blocks. They're 3 miles on the side, each block is about 9 square miles and those were the possible places we wanted trail cameras and we wanted to have one camera per survey block to have good distribution across the state. So, with having 2,000 trail cameras out there, we have a little less than 1/3 of our survey blocks covered. Initially when we rolled out the project, back in 2015, we opened only certain counties across the state—we had one county in the north and one county in the south to try to get good coverage, and then we came up with another 10 counties that we rolled out and made sure that they were spread evenly across the state because we really wanted statewide information to be able to get information about species all across Wisconsin. In 2018 we went statewide, and now anybody from across the state can sign up to put a camera on their own private land or on public land if that survey block doesn't yet have a trail camera on it.

Barred owl | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

Can you talk about how volunteers can interact with the Snapshot program?

There are a lot of ways. We ask volunteers to help us by having one of the trail cameras—signing up and taking the training and putting a camera out on their own private land or on public land. In that case, they're deploying a trail camera and then they're checking at least once every three months to take out the SD card and change the batteries and upload the photos and classify them. But there are ways that everybody can participate, and one of those ways is to help classify photos and the place to do that is on SnapshotWisconsin.org. That's an interface where people can classify Snapshot Wisconsin photos and it's really fun because you get to see the different species that we have. It's almost a game-like interface where you select the species and the count, and then you move on to the next one. You're always wondering which one's going to come up next because they're served up randomly. We have a lot of people that are helping us out from all over the world. Folks can interact with the data on our data dashboard (widnr-snapshotwisconsin.shinyapps.io/DataDashboard). For 19 different species of Wisconsin, you can click on it and see the distribution of that species, you can also see the activity patterns for that species to see when that type of animal is showing up—if they're a nocturnal critter or a diurnal.

Two black bears | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

How do schools participate in the educational arm of the program?

We have some great resources on our website where there are lesson plans. Having students involved has been an important part of the project from the very beginning. Our first 10 public participants were teachers, educators, and their students. They help by having trail cameras on school forests that they can check and then classifying their own photos, but then also classifying photos on Snapshot Wisconsin. If there are educators that are interested, you don't have to be in Wisconsin to participate in this project. You can go to our website and check out some of those resources and download the materials for those lesson plans.

A doe in winter | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

What sort of response have you seen from volunteers?

Our volunteers are fantastic. They seem to really love the project and stick with it. We ask that our trail camera monitor volunteers participate for at least a year and we have very good participation. We've just sent out a round of "thank yous" to the participants that have been with the project for more than five years. The project wouldn't work without volunteers, so we're really grateful to them. One of the things we often try to say about our project is, it's really people powered research. Even in the classification of the photos there's a lot of emphasis these days on computer vision to classify photos—automated classification. Right now we rely 100% on human vision and that is a very precise and accurate way to get the task done. It's incredible we're able to do that.

Coyote pups | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

Have you seen any particularly exciting or surprising images captured?

That's the best part. It's really fun when you see multiple species interacting on camera. There are also photos of the same species and the way that they are behaving together…and you don't know whether they're playing or not, but it's really cool to see.

A coyote and a deer caught on camera together | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

Since the program launched have any notable population trends been observed?

That's a good question. We are starting to have five years of good statewide data and we're just getting to the point of working up the data to look at trends over time. It's a complicated task to translate the photos into a trend because of detection probability.

Winter wolf | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin

What are the program's goals moving forward?

They continue to be the same as what we set out to do—involving the citizens of Wisconsin, and people all over, in monitoring wildlife and providing decision support products to help the Wisconsin DNR and Wisconsin in general understand its wildlife and have good science to make decisions. The one that we've added on, is to contribute to science too. We have a huge amount of data and we've worked with some incredible researchers and graduate students already who have helped us understand the scope and scale of what our data can do to answer questions about animal behavior, animal interactions, and how animals are maybe changing the way they're interacting with each other related to the human pressure that's around. So, this idea of being able to contribute more to research and science is definitely a forward-looking part of the project.

Elk | Courtesy of WI DNR, Snapshot Wisconsin