Cyanobacteria has become a familiar word in areas where there are freshwater lakes and ponds because their rapid growth produces toxins that make humans sick and can kill wildlife or pets who drink the water.

A cyanobacteria "bloom" can close a beach to swimming and other activities during warm weather. Although the blooms usually dissipate within days, monitoring and special testing are necessary before a beach area can be reopened.

Cape Cod, Massachusetts, famous for its ocean beaches and freshwater ponds, has a two-pronged approach to cyanobacteria. These include an active citizen monitoring program during spring and summer, and mitigation efforts to stem the manmade runoff from stormwater, lawn fertilizer and septic system effluent that feeds the cyanobacteria.

Landsat image of Cape Cod. Its 890 ponds, known as the jewels of Cape Cod, are the black areas on the map. Courtesy of NASA

The nonprofit Association to Preserve Cape Cod (APCC) launched a monitoring program in 2017 using summer interns, volunteers, pond associations and local officials. Ponds are regularly sampled from May through October for the level of cyanobacteria, and the information is reported to the public and to relevant town staff. When levels are too high, towns post warning notices.

The APCC also has an outreach program to educate local groups about pond health.

What are cyanobacteria?

Cyanobacteria are ancient microscopic organisms that were the first to use photosynthesis to produce oxygen, changing life on Earth. They are present worldwide in waters and on land, normally in very low concentrations.

Cyanobacteria blooming on a freshwater pond. Courtesy of APCC

Cyanobacteria are also called blue-green algae because high concentrations can turn the water bluish or brownish green. Blooms of cyanobacteria are not always toxic, however, and what causes the organism to produce toxins is not fully understood.

When nutrient levels become high, they allow these blue-green algae to proliferate in freshwater ponds and produce cyanotoxins. The "limiting nutrient" in this process is phosphorus. When available phosphorus is high, often from fertilizer runoff and leaking septic systems, it can lead to harmful algae growth and decreased levels of dissolved oxygen, a process known as eutrophication.

Phosphorus is naturally present in small amounts in the soil and is normally used by plants and microbes for growth. But even small increases of phosphorus above normal levels can lead to algae blooms.

Cyanobacteria from genus Dolichospermum as seen under a microscope. Courtesy of Masa Zupancic/Creative Commons

Cyanobacteria toxins

The two common forms of cyanobacteria in Cape Cod ponds are Dolichospermum and Microcystis. Both produce toxins that cause liver damage (hepatotoxins), toxins that cause skin irritation (dermatoxins), and toxins that cause neurological damage (neurotoxins).

These cyanobacteria also produce microcystin, which is the only toxin monitored by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. This toxin causes liver damage but at different rates. Dolichospermum produces relatively low levels of microcystin while Microcystis produces relatively high levels.

When microcystin levels are above the state standard of 8 parts per billion, a pond is considered unsafe for use by humans and pets, and its use is restricted.

There are three categories of cyanobacteria risk in a monitoring program:

1) Acceptable (cyanobacteria levels are not of concern for water quality).

2) Potential for concern (indicating the presence of some cyanobacteria).

3) Use restriction warranted (levels of cyanobacteria make the water unsafe).

High levels of cyanobacteria make the pond water unsafe for humans, pets, and wildlife. Courtesy of APCC

What feeds cyanobacteria?

Phosphorus is part of the energy-generating process in every living cell, including those of humans.

Increasing human activities near water bodies can deposit excessive levels of nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, in the waters, "feeding" the cyanobacteria and promoting blooms. Warm weather creates optimal growing conditions. Sometimes the cyanobacteria produce a scum, foam or mat floating on the surface or collecting at the shoreline.

Santuit Pond, Mashpee, with cyanobacteria scum. Photo by Gerald Beetham/APCC

Excessive levels of nutrients in waterbodies come from human-related sources such as lawn fertilizers, human and pet waste, and runoff from roadways. Most of Cape Cod relies on septic systems (and some cesspools), which release phosphorus and other nutrients into the soil.

Stormwater runoff speeds the transport of this effluent, along with lawn fertilizer runoff and pet and wildlife waste, into the fresh waters.

Mitigation efforts include:

• Building sewer systems to minimize the nutrient flow (a slow process).

• Limiting fertilizer use.

• Requiring septic system maintenance.

• Keeping duck and geese populations away from the water by not feeding them.

• Planting vegetative buffers near the water, to block the path of nutrients.

• Treating ponds with alum (potassium aluminum sulfate), a common chemical used in pickling, which binds with the phosphorous and immobilizes it (A few Cape ponds have been treated with alum to reduce blooms).

Barnstable's Karen Malkus training volunteers from the Brewster Ponds Coalition in monitoring cyanobacteria. Photo by Gerald Beetham/APCC

The political dimension

The political battle is between developers and contractors who want to keep building new housing, and environmentalists and small-town advocates who want to limit new construction until sewers and other measures are in place to limit the wastewater food chain for cyanobacteria.

Environmental activists say that Cape Cod has reached its carrying capacity and cannot support any more development. Meanwhile, free enterprise activists argue that landowners should be able to do what they please with their land, and it's "un-American" to limit them.

Meanwhile, the one-celled cyanobacteria are carrying on, blooming and producing toxins when their food chain is plentiful, and the weather warm.

Monitoring cyanobacteria: An essential step in reversing decades of water quality decline

Andrew Gottlieb, head of the Association to Preserve Cape Cod, has more than 30 years of environmental protection experience in government and as an elected town official. During his 16 years at the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, he developed its estuaries preservation program and built an innovative revolving fund into the nationally recognized model for watershed protection funding.

Kinute recently spoke with Gottlieb about APCC’s monitoring program and the essential steps it’s taking to reverse decades of water quality decline.

Q: What has the APCC's cyanobacteria monitoring program accomplished this year?

A: This past summer, with the help of pond group volunteers, Cape Cod towns and the county, we monitored 130 sites on a regular basis in all 15 towns. Twenty-four of those 130 ponds experienced harmful cyanobacteria blooms and received at least one municipal advisory or closure by a town health agent.

In general, although the number of advisories in 2022 was similar to years past, we had larger cyanobacteria blooms this year. We suspect that the hot summer and drought conditions were contributing factors.

APCC Executive Director Andrew Gottlieb. Courtesy of APCC

APCC Executive Director Andrew Gottlieb. Courtesy of APCC

Q: How does the APCC monitoring program work?

A: We partner with officials at the town, county, state and federal levels as well as local pond associations and residents to conduct cyanobacteria monitoring in our ponds.

Each season, data are collected biweekly and shared with local officials and the general public through reports, emails, and our interactive map of monitoring results. Results are communicated as either “acceptable,” “potential for concern,” or “use restriction warranted.”

Q: Are town governments on the Cape collaborating with APCC?

A: APCC partners with several towns to perform cyanobacteria monitoring. For those towns where we have monitoring contracts, APCC works under the direction of the town to select sampling locations and frequency.

Volunteers in the APCC cyanobacteria program at work. Courtesy of APCC

Volunteers in the APCC cyanobacteria program at work. Courtesy of APCC

Where APCC is not contracted by the town, sampling may be supported by other partners, or we may do it on our own. In all cases, APCC shares its results with town health agents to maximize the sharing of information and protection of public health.

Q: Do you think the problem is worse on Cape Cod than other communities?

A: Cyanobacteria outbreaks are a global phenomenon. It's impossible to say if it's worse on the Cape or not. What we do know is that the Northeast is warming at a greater rate than many parts of the world, and that Cape Cod soils enable the rapid transport of nutrients through groundwater to surface waters. These conditions make the Cape very susceptible to cyanobacteria outbreaks.

Q: The APCC monitoring has been for the Cape’s freshwater ponds. What about the cyanobacteria problem in some ocean beach areas?

A: There is clearly a connection between freshwater ponds and estuarine resource areas, but the full understanding of the presence of cyanobacteria in the Cape’s marine environment is still developing. We have done some assessments, but don’t yet know how big a concern that is.

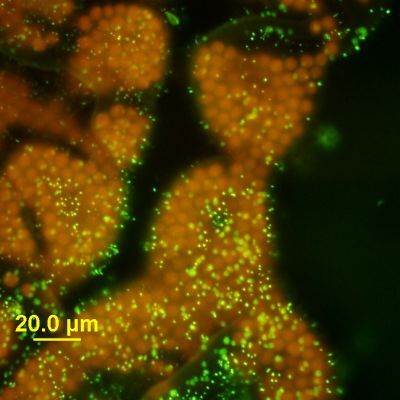

Microcystis wesenbergii colony (cyanobacteria) under epifluorescence microscopy and stained with green DNA dye. Courtesy of Dr. Barry Rosen/USGS

Microcystis wesenbergii colony (cyanobacteria) under epifluorescence microscopy and stained with green DNA dye. Courtesy of Dr. Barry Rosen/USGS

Q: What policy changes does the APCC recommend to curb the runoff from fertilizer and septic systems?

A: Septic systems are largely the cause of nutrient pollution and are driving poor water quality across the Cape. In general we advocate for the replacement of septic systems that are near sensitive surface waters.

Converting landscapes to native species and minimizing manicured turf lawns, and minimizing fertilizer would be very helpful in improving water quality. A green lawn helps you get a green pond, and the trade-off does not seem worth it.

You can find detailed recommendations for policy action at the state, federal, county and town levels at capecodwaters.org, along with APCC’s annual State of the Waters: Cape Cod report.

Cyanobacteria on Scargo Lake, Dennis. Courtesy of APCC

Cyanobacteria on Scargo Lake, Dennis. Courtesy of APCC

Q: What role does the state government play?

A: The state government is proposing new standards for septic system performance that will help improve water quality. We hope to see the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection's proposed improvements to Title 5 septic regulations and watershed permit rules finalized by the incoming administration of Gov. Maura Healey.

The state also plays a big role through the Department of Public Health, which has come a long way in recognizing the scope of the problem on Cape Cod. We encourage the department to continue to support local health agents in the development of protective responses to the cyanobacteria conditions we report.

Q: What do you see as APCC's future role in keeping Cape Cod's waters unpolluted?

A: Water quality is APCC’s highest priority. We plan to continue to promote understanding of the challenges our region faces. And we will develop and share data, propose funding mechanisms to minimize the financial impact on homeowners and push towns to act.

APCC sees itself as central to creating and maintaining the political consensus necessary to reverse decades of water quality decline.