Amidst the insistent hum of modern life, artist Isabella Kirkland invites us to slow down.

Kirkland’s realistic depiction of subjects in the natural world beckons observers closer and asks us to consider our relationship to the fabric of life.

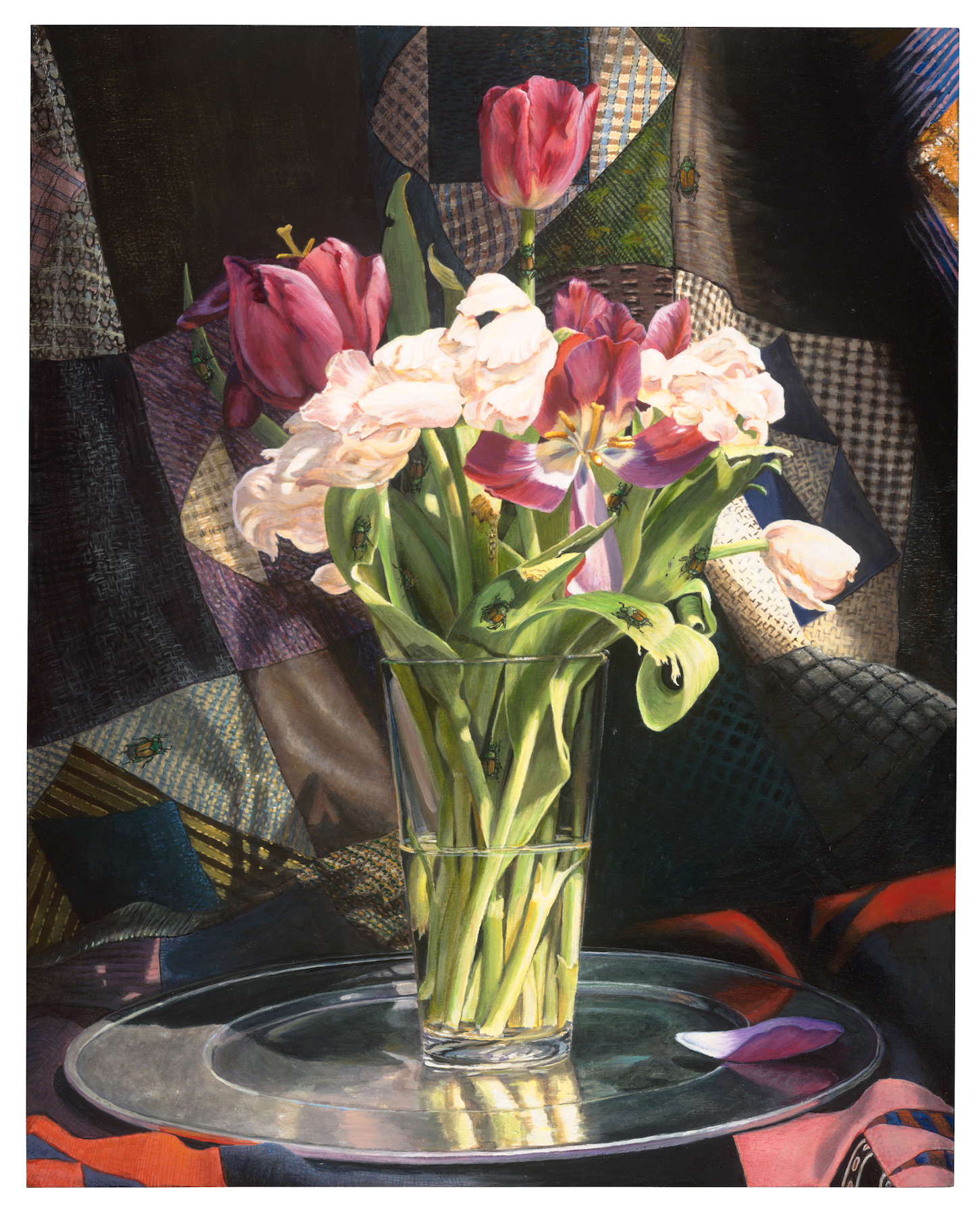

New Opportunist | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

Self-taught in the realistic style of the 17th-century Dutch masters, she crafts this invitation with exact detail, often depicting smaller subject matter.

“One of the reasons my paintings are complex and minutely rendered is to draw viewers in close, to slow them down,” Kirkland said in an interview with Kinute. “Most museumgoers typically spend but a few seconds in front of a piece of art. If I can make viewers linger, there is a possibility for learning and reflection.”

The Hosfelt Gallery in San Francisco recently held an exhibition of Kirkland’s work. A statement from their website highlights the intimacy of her subject matter, stating “In the world of environmental activism and nature documentaries, much attention is given to the large, majestic animals facing habitat loss and extinction…Kirkland instead turns her focus to the more minute organisms that tend to go unnoticed, but that make up the majority of the natural world.”

Mixed Box with Uraniids | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

Kirkland wants people to see that every creature and plant, no matter how big or small, have as much right to live as humans. “With the loss of even a little thread, the fabric of our planet's biological systems weakens.”

Through her work, her hope is for people to gain a greater sense of understanding of the environment and take responsibility for their own ecological footprint, even if they are unaware of it.

“If I can inspire even one young person to become a conservationist or taxonomist or scientist, my job is done,” she said.

Old Opportunist | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

Following the thread

Kirkland’s love of the natural world and for creating art began in her youth. "An artist is what I have wanted to be since before I could read. I’ve been a maker all of my life,” she said.

Born in rural Connecticut and reared in Virginia, Kirkland was one of five children. “I had a spectacular childhood,” she said, and a highlight of this era was “the privilege of roaming my great aunt and uncle's 500-hundred-acre farm on the James River, across from a game preserve.”

Descendant | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

Her lifetime loves were fortified by her parents, recounting that, “[My] mother was quite a capable artist, specializing in pastel portraiture.” She fondly remembers that “Sometimes I would stay home and do art projects with my mom.” Additionally, she said, “[My] father was an avid outdoorsman, conservationist, and superb fly-fisherman.”

Kirkland has done the bi-coastal flip flop many times in her life. In the early 1970s she was living in California and had the opportunity to work for CoEvolution Quarterly (CQ), a publication she summarized as “An iconic magazine focused on ideas, ecology, technology, and tools.”

She recounted that, “Among the many illustrious thinkers and writers who published their ideas in CQ was Peter Warshall, evolutionary biologist extraordinaire. He and others introduced me to thinking of nature as ecological systems instead of individual organisms.” This planted a seed that forever changed the face and direction of her work.

Gone | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

By the late 1980s Kirkland began art directing films, to financially support her art making. Of the experience she recounted, “There I was struck by the tremendous waste involved in their production. Pallets of plywood, hundreds of gallons of paint, explosives and cars, and untold amounts of energy and copious other materials, all dumped after being used to create an illusory moment on screen.”

In a purposeful departure from this world of waste, Kirkland realized that “Painting, on the other hand, uses scant supplies, mere tablespoons of pigments. In an effort to reduce my own ecological footprint, I decided to explore how two-dimensional image-making could be used to speak about humanity's relationship to the natural world.”

This shift in medium and focus, aligned her two great passions and drove her to perfect a realistic style that has the power to speak to audiences now and well into the future, saying, “I realized that it might be possible to speak to viewers 500 years in the future if the paintings are made well enough and of the most durable materials.”

Kirkland is driven by the power of this possibility, saying, “My work is an effort to preserve, as accurately as possible, analog images of species of plants and animals we are likely to lose in the coming century.”

Back | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

A labor of love

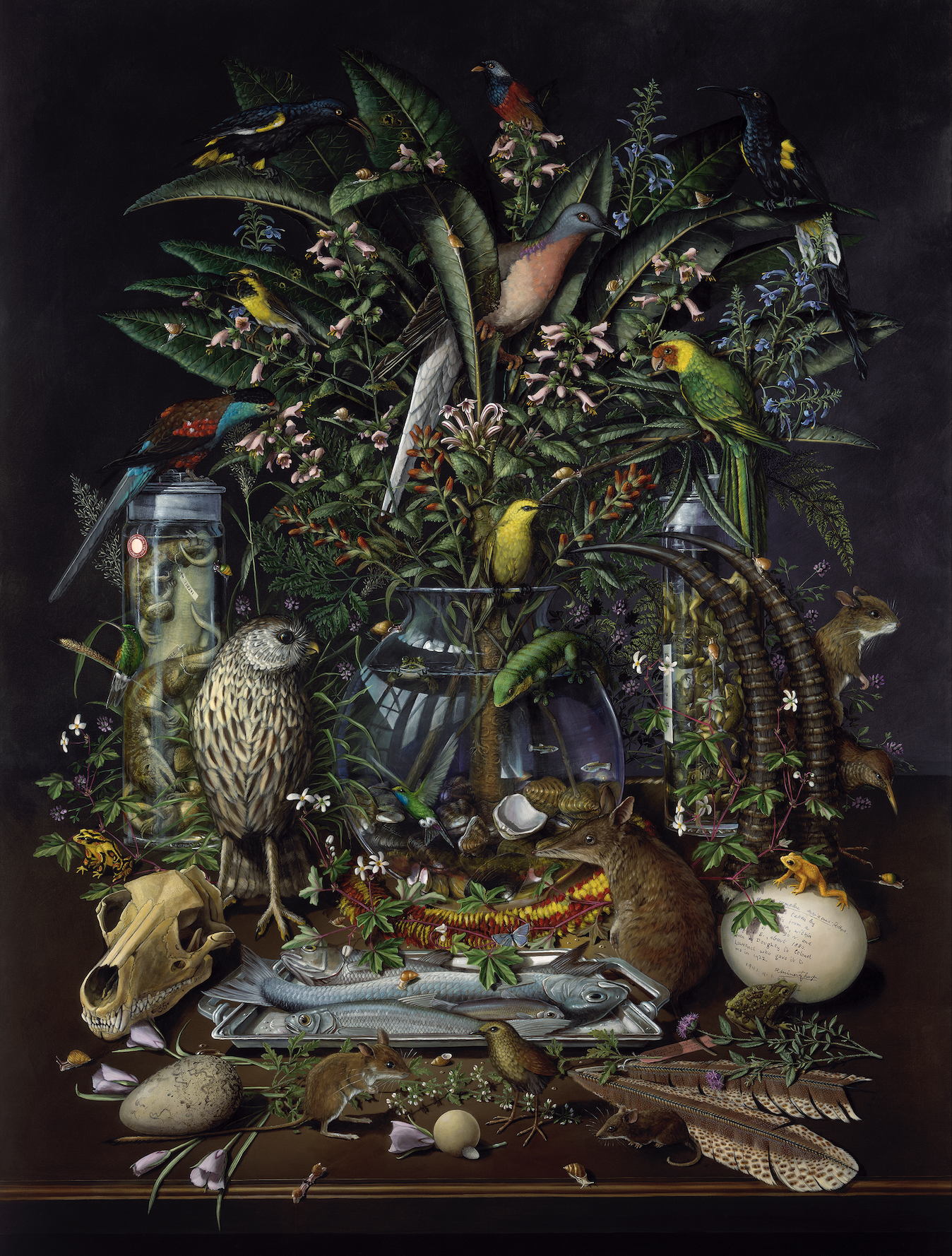

Since honing her signature style and subject matter focus, Kirkland has often composed collections that are woven together by a unifying factor. “My pictures begin as a database of biota that fit a particular rubric, a rule if you will, such as ‘all are extinct,’ or ‘all have been re-found after thought of being extinct,’” she says.

Her methods are a study in attention, as is evidenced by the finished piece. Compositions often feature numerous species — each of which are thoroughly researched, photographed and sometimes drawn from study skins or preserved specimens at natural history museums. “Each is drawn to scale, so that I may represent them in relative life size,” Kirkland said.

She then imagines how to arrange each specimen and makes a full drawing of what the finished piece will look like before transferring it to canvas. This is all before any painting takes place. “The whole process of making a large painting takes about a year,” Kirkland said. “It is a labor of love.”

Paradise Parrots | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

The precision and subject matter of her work pushes Kirkland beyond the realm of strictly art and into the scientific sphere as well. Her work has been exhibited in both art and science museums.

Kirkland considers it, “A pleasure and an honor to celebrate the biodiversity conservationists, scientists, concerned citizens, organizations, and individuals work so hard to protect.” Noting that, “I take the educational aspect of this work seriously, in part, by including the data from which I work in my exhibits.”

This educational component is at the heart of her mission — to request attention for the small and vulnerable members of nature who lack a voice, to elicit further thought from the witnesses of her work, to call to action all members of the overly dominant species affecting the future of the Earth.

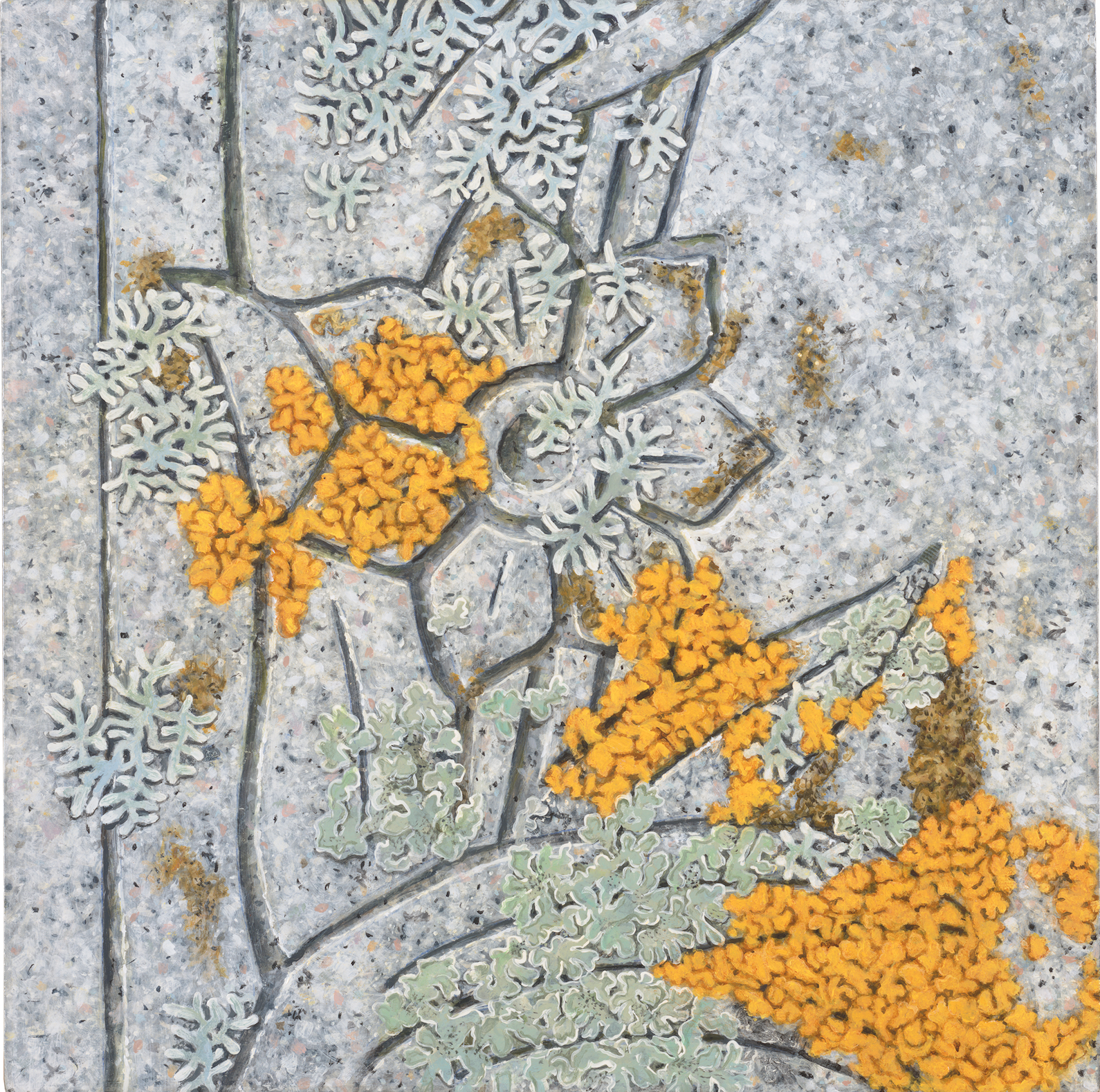

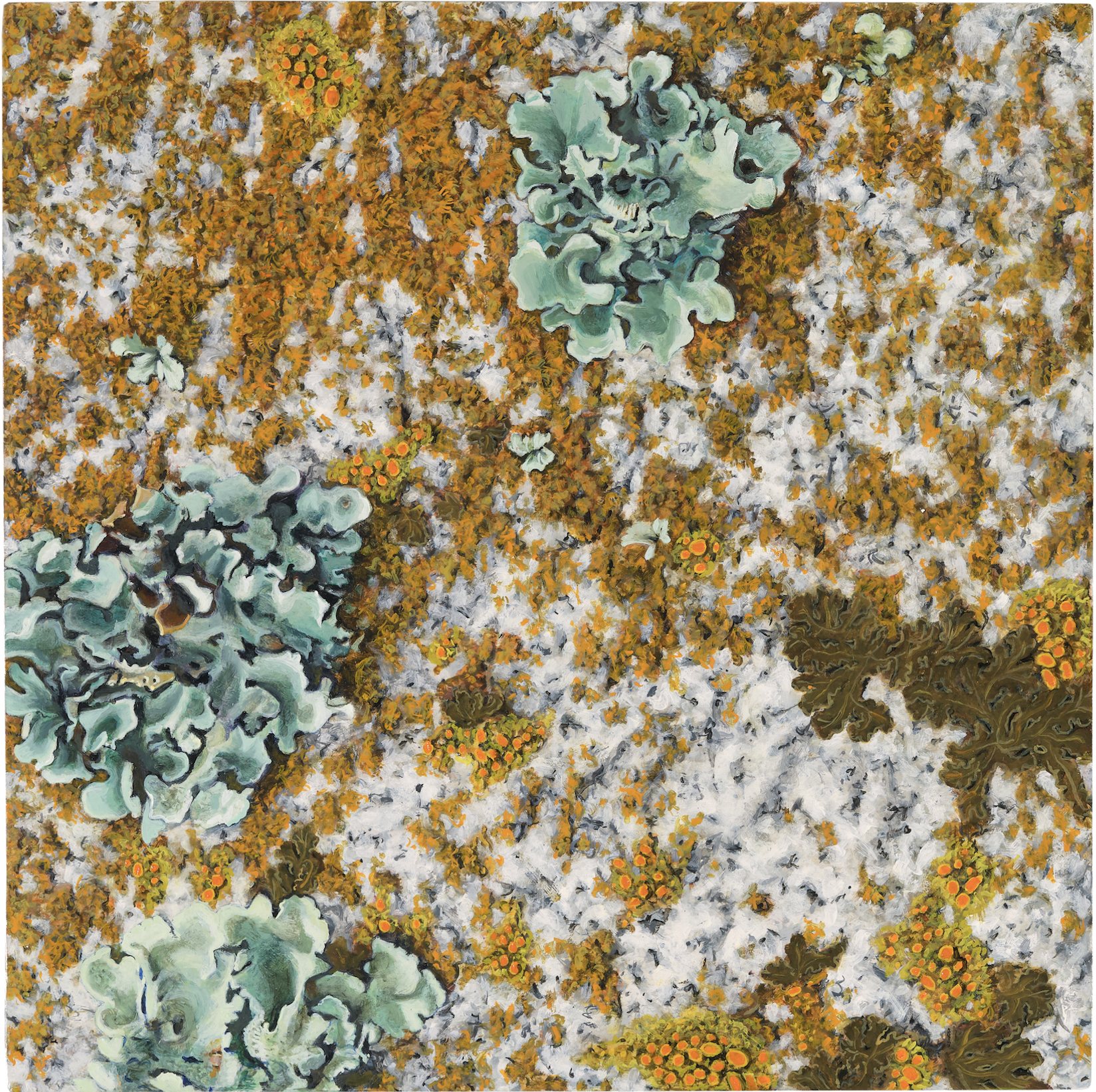

Gravestone Lichens II | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

Delighting in the details

To view Kirkland’s work is to audit a masterclass in attention. She is magnetically drawn to what is nearly impossible to capture, saying, “What I paint most often is the light between objects, that most ineffable of subjects to capture.”

She goes on to explain, “I have no favorite color, animal, plant, or place. I am inspired by the very thing I am working on at the moment, trying to give it my full attention — but in relation to all else around it.”

Indeed, upon viewing her work, no preferential subject can be identified. Kirkland offers the reverence of her attention to all her subjects, from the haunting face of the elusive Madagascar red owl returning the gaze of the observer in her painting Back, to the lichen that are the otherworldly and tranquil subjects of her Gravestone Lichens series.

Graveyard Lichens V | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

While Kirkland recognizes that, “Many of my paintings are quietly disturbing: they do often document subjects that are in decline or are vulnerable to extinction,” she does note that, “I also like to show off some of the smallest denizens that often go overlooked such as tree-hoppers or squat lobsters.”

Of these improbable creatures, she says, “Life itself is often more surprising than fiction.”

She also delights at nature’s creative problem solving, saying, “Evolution has caused many, what appear to us as extremely curious, solutions for circumventing extinction. But upon closer inspection, these solutions usually make perfect sense within the species' own life.”

Expounding on this, she cites, “Nudibranchs, for example, appear clownishly colorful, particularly since nudibranchs are almost entirely blind. But their mad patterns serve various functions: to advertise toxicity, to blend in perfectly with their background, or to mimic another species that is toxic. There is always a reason, whether we know it or not.”

Graveyard Lichens VIII | Image courtesy of the artist and Hosfelt Gallery, Photo by Ben Blackwell

This willingness to observe, listen, and learn is a tenet that sometimes feels as close to the brink of extinction as some of the species that Kirkland catalogues in her work. This is the precise reason she continues to hone her craft and give voice to the creatures she depicts — in hopes of inspiring action in others.

There is a reason why, in the face of such realistic portrayals of nature, observers find it almost impossible not to reach out their hands to touch the subjects. It is as if observers wish to walk through the veil of the painting and absorb the wordless lessons of the subjects, to commune with the wisdom we feel deep within us, yet somehow find inaccessible.

Through her art, Kirkland calls us to action and we are called to answer, even if we are uncertain of what that answer is. Like all species that evolve, we are called to take the next right action.

To view more of Kirkland's work, visit isabellakirkland.com.