Sue Tidwell is inviting you along on a “grand adventure” — exploring Africa during a safari while learning about the continent’s people and animals and the myriad issues impacting them.

Her book “Cries of the Savanna” came out in November. It was inspired by Tidwell’s experience in Tanzania, Africa, where she reluctantly tagged along on a big-game hunting safari and came face-to-face with the complexities of African wildlife conservation.

Through the book, she hopes to spread awareness about the extraordinary animals of Africa and promote enough conservation to keep them alive, while also improving the welfare of the continent's rural human citizens. She said the title was chosen very carefully, and for a pair of reasons.

'Cries of the Savannah' was published in November. Photo courtesy of Sue Tidwell

“The title has a double meaning. I fell in love with the cries of the savanna! Literally!” she said in an online interview with Kinute. “Every single night, the vocal shenanigans of beastly creatures varied, a different composition of growls, squeaks, bellows, chortles, and a hundred other ghostly serenades. The primal sounds chilled me to the bone but, at the same time, filled me with awe.

“Never have I felt so alive and exhilarated by the promise of the days to come,” Tidwell said. “Yet, I also came to recognize the dangers of living with such dangerous, destructive species and observed the strategies necessary to mitigate those risks.”

She said the second meaning of the title is a cry for the world to understand how this experience changed her forever.

“The truth is, I am not the same having heard the cries of the savanna,” Tidwell said. “Not only their savage songs, but their cries for the world to awaken and to understand the hard-truth needed to ensure their cries forever remain a part of the wild, and not just ghostly echoes from a distant past.”

To do so, she brings readers along, allowing them to experience the magic and peril of Africa through the eyes of someone encountering its magic for the first time.

“I want them to get to know the people of Africa and come to care about them like I do,” Tidwell said. “Ultimately, I hope that readers come to understand that the welfare of the often-marginalized people of rural Africa and wildlife conservation are inextricably linked. Wildlife cannot prosper unless its human counterparts feel a tangible benefit from their existence.”

Tidwell, 60, was surrounded by animals when she grew up in a small town in rural Pennsylvania, spending much of her early life adventuring through the woods where she often saved baby squirrels, looked for salamanders and snails, and fished for catfish. At 5 years old she had already solidified a passion for the outdoors, nature, wildlife and adventure.

“Although I am a non-hunter, I grew up in rural Pennsylvania where many people did hunt deer and turkey. So, I had a basic understanding of its general merits, especially for subsistence and population control,” she said. “Ultimately, I ended up marrying a hunter. It wasn’t until my husband wanted to hunt in Africa that my stomach did flip-flops. Somehow, the idea of hunting Africa’s exotic animals — especially certain prized species that I had adored since childhood — seemed different from hunting deer, turkey, and elk.

“Weren’t some of the species endangered? Wasn’t photo tourism a better way to protect lions and elephants?” Tidwell said. “Ultimately, my zest for adventure and desperation to experience Africa trumped my misgivings; I put on my big girl pants, packed a bag and headed for the Tanzanian bush.”

She discovered a world unknown to her before, a place dazzling and disturbing, beautiful and tragic. It took some time to grasp and digest what she had experienced.

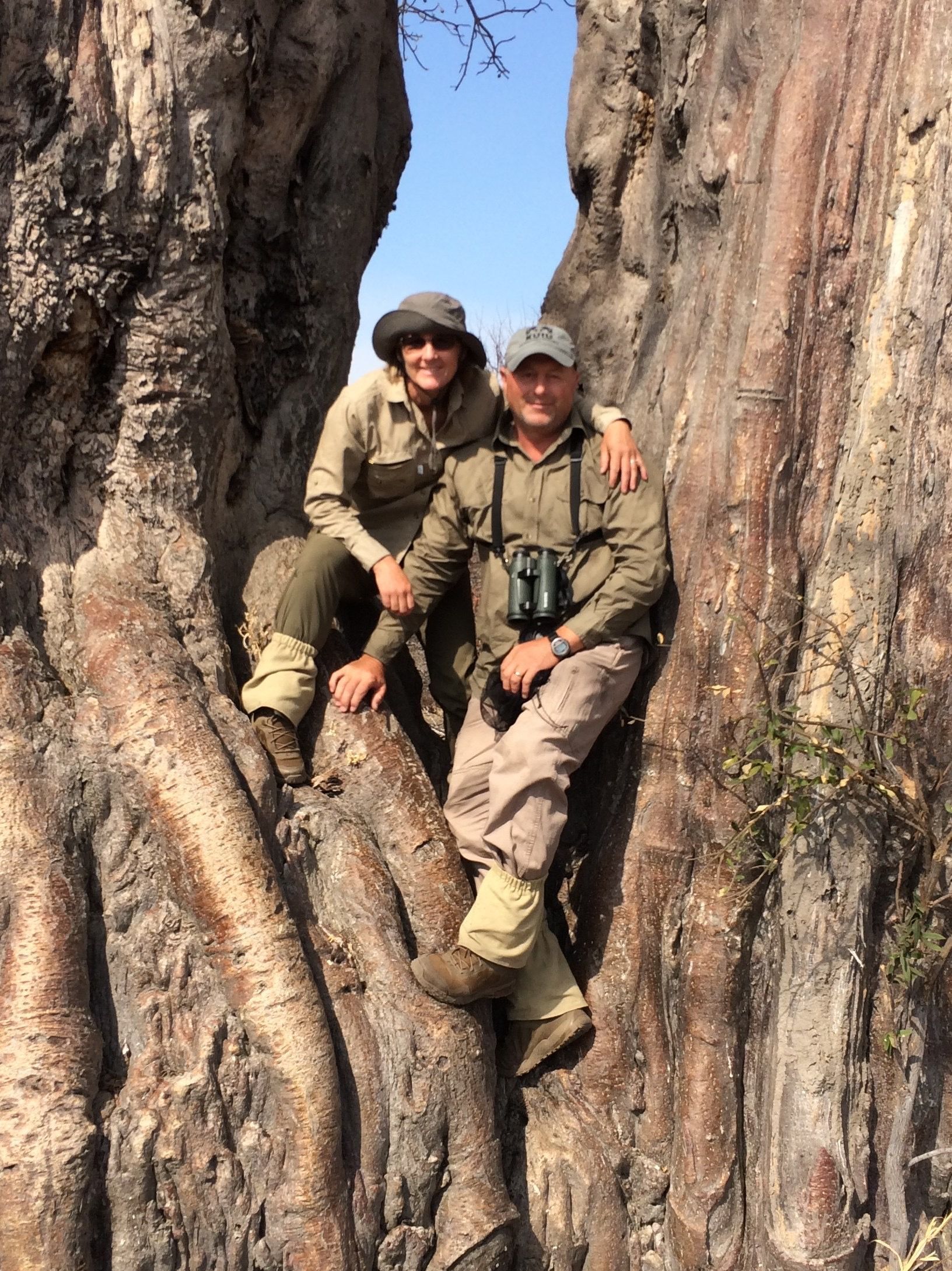

Rick and Sue Tidwell in front of a boabab tree. Photo courtesy of Sue Tidwell

“It, therefore, wasn’t one huge ‘Aha’ moment that exposed me the complexities of wildlife conservation in Africa, it was 100 little truths,” Tidwell said. “From the moment you step off of the airplane, you are confronted with a reality that most Westerners cannot comprehend. The city of Arusha seemed to be bursting at the seams: small herds of cattle being were being driven down the dirt roads; women carrying huge loads on top of their heads were intermixed with man-powered carts and wagons overflowing with goods; scooters, motorbikes, and a few cars navigated as best they could around the hustle bustle of the streets.

“Then we were whisked off on a 2-hour charter plane to get to a remote part of Tanzania. Instantly, we were confronted with the blood-sucking and disease-carrying Tsetse flies that can make life in the bush a living hell, pardon the language,” she recalled. “Once we got to camp, we found that ALL of our water came from a 3-foot hole in the ground dug in the sand of the dried-up Mzombe River.”

There were other, more dangerous concerns.

“Then we were told ‘Do not step outside your tent at night — no matter what!’ After all, you don’t want to bump into a lion or hyena who might consider you a nice piece of rump roast,” she said. “Next, we were informed 'Camp very safe, very safe … but' be sure to keep your eyes open for black mambas and other unsavory serpents who tend to hang out in the rafters of grass huts.”

The harsh realities of other issues were evident as well.

“Once we were out on safari, we came across elephant bones and a whole new type of reality hit us,” Tidwell said. “Did you know there are MANY types of poaching? We tend to think of poaching for rhino horns and elephant tusks but there is sustenance and commercial bushmeat poaching, honey poaching, timber poaching, illegal fishing, etc. The list goes on. All of this — when unregulated — is devastating to the wildlife and the habitat that they need to survive.”

The sun sets behind a tree on an African plain. Photo by Damian Patkowski / Unsplash

Forming a friendship

She said it’s important to note that Tanzania sends a game scout, not connected to the concessionaire, with every hunting party to document everything and make sure all the harvests are legal. This person is not affiliated with the hunting concession in any way.

“We were fortunate enough to be assigned a very intelligent and knowledgeable young woman named Lilian who spoke pretty darn good English, which made talking easy,” Tidwell said. “Bouncing around on the pitted roads of Rungwa West Game Reserve, battling Tsetsie flies together for 9 to 13 hours a day in temperatures hot enough to scald a lizard, allowed us to become fast friends. After all, misery loves company. Anyway, Lilian opened my eyes up to the reality of Africa and the complexities of conservation instead of the fairy-tale version I had envisioned since childhood.”

Lilian, a game scout, and Sue Tidwell pose atop Chui Rock. Photo courtesy of Sue Tidwell

Her husband, Rick Tidwell, grew up on a small ranch in northern Idaho where the sustainable use of wildlife was part of his lifestyle.

“While hunting in Africa had been a dream of his since his early childhood, time constraints and money never permitted it,” she said. “When my brother died of cancer, shattering us both, we recognized that you have to MAKE your dreams happen; you can’t just wait for the ‘right’ time. We sold a bunch of stuff and booked our trip to Tanzania. So, yes, this was also his first safari.

“He hunted zebra, kudu, impala, Cape buffalo, roan, eland, sable, dik dik, oribi, hartebeest, spotted hyena, and a few other species,” Tidwell said. “That being said, just because you are hunting them doesn’t mean you succeed! Sustainable use of wildlife — or conservation hunting — means that only old males past their breeding age and no longer spreading their genes are targeted.”

Wild species do not grow to a ripe old age without a healthy dose of smarts, along with a lot of luck, she said, so hunters are not guaranteed success.

“Just like us, years of experience teaches them a thing or two. Also, since nature takes its toll on wild species, aged animals are fewer and farther between,” Tidwell said. “Therefore, hunting wiser game, much shorter in supply, creates a much greater challenge to hunters. The large amount of money, time, and torment involved in hunting such clever specimens often ends with hunter’s coming home empty-handed.

“Also, in Africa, you pay a ‘trophy‘ fee per animal on top of the safari price and each animal costs a different amount depending on its population and a lot of other factors (supply and demand comes into play),” she said. “When hunting in Africa, the hunter must make decisions on which animals he or she can afford to harvest.”

Rick Tidwell succeeded with several of the animals listed above but Sue declined to specify his harvests.

“Let’s just say that one of the species that I was so opposed to him hunting, because I was emotionally attached to it and thought it would be like shooting fish in a barrel, became our nemesis,” she said. “Each African nation is slightly different but essentially, any wildlife that can be sustainably harvested and is allotted by the government can be hunted, with very specific guidelines in place.

“Unless it is a special situation, harvested animals must be old males past breeding age and nearing the end of their life spans,” Tidwell said. “For instance, after we’d pursued a kudu and my husband had him in his sights, our professional hunter suddenly called it off. He determined that the bull, sporting 48-inch horns, was still in its prime and, therefore, had a few more years of living to do.”

With long, spiraled horns, kudus are one of the largest antelopes in the world. Photo by Dmitrii Zhodzishskii / Unsplash

It’s the difference of inches, the issues of people and governments, and the eons of history that make the matter so complex. She said she learned “many, many things” that she explores in the book. Some were real eye-openers.

"First of all, the wildlife that Westerners are emotionally attached to — species like lions, leopards, hippos, and elephants — are dangerous, destructive and deadly,” Tidwell said. “Lions and leopards kill the livestock that they depend on for their livelihoods. Elephants can wipe out a villager's entire crop in one overnight raid and destroy their water systems and infrastructure. Both of these species kill hundreds of people a year in Africa.

“Hippos, too, are not roly-poly good-natured water lovers; they are grouchy and territorial, killing hundreds of people a year. Most of the people who live in proximity to these creatures are impoverished and food-insecure,” she said. “Quite simply, their lives would be safer and easier without such animals. Honestly, until I was in Tanzania, it had never occurred to me that the rural people of Africa might not have the same fondness for the animals that we adore from afar.”

A hippo made itself at home in a puddle near Tidwell's tent. The massive animals are very dangerous, killing hundreds of people annually. Photo courtesy of Sue Tidwell

She said Lilian taught her that wildlife is often killed in retaliation and preventative measures, frequently with the use of poisons. That adds yet another element to deal with, however.

“The poison, of course, not only kill the targeted animals, it kills anything that feeds upon the tainted carcasses,” Tidwell said. “That is one reason why the sustainable use of wildlife is so important. It provides a financial incentive to mitigate the conflict and ultimately protect wildlife.

“Here is perfect example of the complexities involved. A village was gifted goats to elevate their human condition and deter them from poaching,” she said. “However, the livestock also attracted carnivores which ended up resulting in the killing of carnivores. The well-intentioned strategy led to the death of the species most threatened.”

But she said while human-wildlife conflict and poaching are both “huge” issues, they pale in comparison to habitat loss.

“Africa’s population is growing like crazy and consuming land and resources along with it. Well-managed hunting makes land valuable in its natural state instead of being turned into other human uses,” Tidwell said. “Policies for wildlife conservation must take the human factor into consideration and be based on facts and statistics, not emotions.

“The ‘Disneyization’ of wildlife, as it is often referred to, ultimately sabotages conservation efforts,” she said. “In Glen Martin’s book ‘Game Changer: Animal Rights and the Fate of Africa’s Wildlife,’ it suggests that biggest threat to wildlife is the “growing disconnect between the ideal and the real — the sense that ‘loving animals’ is the same as saving wildlife. As animal rights advocates gain influence in East Africa … it becomes harder to implement effective conservation programs, because some of those programs may involve killing animals.”

These are topics and issues she can discuss at length. It’s one reason she felt the need to share her views on them in the book. Tidwell said for years, friends urged her to write a book. But it wasn’t until her trip to Tanzania that she felt driven to do so.

A promise kept

“Before leaving Africa, I promised Lilian that I would try to help the world understand. ‘Cries of the Savanna’ is the result of that pledge,” Tidwell said. “Experiencing Africa first-hand offered me a whole new perspective, answering all the questions that had troubled me. Although there are plenty of facts that support the value of well-managed hunting, I no longer needed statistics; common sense and my heart told me everything that I needed to know.

Lilian served as a guard for Sue Tidwell as a hippo settled into a nearby puddle. Photo courtesy of Sue Tidwell

“Still, I knew that I had to back up what I learned with facts. The more I researched — using boots-on-the-ground biologists and conservation organizations not affiliated with hunting — the more my passion grew.”

She said she felt a calling to write this book. That, and a pledge to a friend she met during this life-altering experience, set her to work, Tidwell said.

“The book wasn’t written out of a desire to see my name in print or to fulfill a lifelong goal, it was written because of a promise to Lilian — and because, I believe that I was meant to write it,” she said. “For over three years, I lived and breathed Africa. My days were spent camped at the computer when the sun was shining outside and my paddleboard was calling my name. Even when not at the keyboard, my mind was in some far-off distant place. Recently, my husband found our rice cooker in the refrigerator instead of in the pantry!

“Nights offered little relief. Hours that were supposed to be restful and restorative were tormenting, as I rewrote passages in my head, searching for the perfect words or stressing over the details required for self-publishing,” Tidwell said. “Yet, if this book can give rural Africans a voice and help people understand the conservation benefits of the sustainable use of resources, I don’t regret a moment of it.”

The photos in the book are important because they bring the people and animals to life, offering a glimpse of existence on a continent that many imagine but few every really get to know, she said.

“By sharing the faces of the people that I became attached to, my hope is that readers will become attached to them as well,” Tidwell said. “I want them to care about the people of Africa as well as the wildlife.”

While crafting this book was a passion project that she hopes finds a receptive audience, a follow-up isn’t immediately in the works. The couple lives in rural northern Idaho in a small ranching/farming community.

“I never had a career in the writing industry. I grew up in rural Pennsylvania in a blue collar family where a college education was never even talked about. My work experience is quite unique. Along with some years of waitressing, I worked for 10 years as a steel mill worker. Then I moved to Alaska and got hired as a flight attendant,” Tidwell said. “So I went from wearing steel toe boots, metatarsal wristlets, and side-shield safety glasses in a dreary steel mill to donning a uniform with wings in the most beautiful work environment ever, the skies of Alaska. That is where I met my husband."

They relocated to his hometown of Idaho in order for his daughter to live with them, and Tidwell worked as a medical secretary and waitress in addition to remodeling “fixer-uppers” with her husband.

“In other words, I became great at using a sledgehammer, crowbar, and paint brush,” she said.

Tidwell has never hunted, and has no desire to pull a trigger. But she has accompanied her husband on his hunts, and eaten the meat he has taken. In a way, that makes her a hypocrite, she said. While she has never hunted, writing also was something she never planned to do.

“The extent of my writing was adventure-filled Christmas letters each year to my family and friends. Many of my friends raved about my writing, insisting that I need to write a book about my crazy adventures and misadventures but I figured who, other than friends, wanted to read about my follies?

“Honestly, I don’t fit the stereotype of a writer. I didn’t feel the burning desire to put my words on paper or spend countless hours at the keyboard. That is, until I went to Africa,” Tidwell said. “My Tanzanian safari lit a fire in my gut, compelling me share my adventure and journey of awareness with the world. ... I don’t believe in coincidences; I believe everything in my life led me to this moment.

For more information or to read the first chapter of the book as well as reviews, go to suetidwell.com.

You also can read reviews on her Amazon page.