Former U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt said that a nation that destroys its soils is a nation that destroys itself. “Forests are the lungs of our land,” the 32nd president said in his 1937 plea to all American state governors for action in conservation and soil management, “purifying the air and giving fresh strength to our people.”

If trees are the planet’s lungs, is humanity the cigarette smoke? There are roughly 420 trees on Earth for every human, according to population data from 2020 and environmental research data from 2022, but mankind has been far from merciful to these providers of shade, shelter, food, and biodiversity. There are half as many trees on the planet as there were when human civilization began, and every year the population dwindles to provide timber, land, paper products and whatever else is demanded of Earth's finite forests.

Many are still singing the same song that Roosevelt did 85 years ago. And after decades the work is paying off, bit by bit and root by root.

Planting the seed

One of those people doing the work is photographer Dave Van de Mark. Nearly 60 years ago, Van de Mark, now 79, trespassed on private land, chartered airplanes for aerial views of clear cuts, slept on stream banks and walked over 1,000 miles to capture thousands of photographs that exposed the destruction of the famous California redwoods. The photographer's efforts would eventually help establish Redwood National and State Parks.

It was June 1963. Van de Mark, 20 years old and living in southern California at the time, hadn't truly experienced environmental damage to wild spaces firsthand yet. After high school, he headed north to work in a sawmill, using his off time to intensely explore sweeping tracts of redwood forest throughout upper California. The landscape he saw, a jagged massacre of harvested redwoods, was a heartbreak.

Three backpackers hike along Emerald Mile on Nov. 24, 1967. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

Dave Van de Mark takes a picture of the same grove of trees on Nov. 8, 2018. Now, Redwood Creek is hidden from view and is flowing much lower (down below the hardwoods) because flood gravels have had a chance to be carried away. The hardwoods and young conifers are growing in front of the grove face, acting as protection. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

"You saw pictures of so-called destruction of forests all the time in the news, but that was too abstract and it possessed no sense of urgency—you were seeing what already had happened somewhere," he recalled to Kinute.

Van de Mark is son of a longtime timber industry executive. If he expressed concern about the redwood forests, his father responded that the redwoods not located within state parks had "been logged off—a done deal."

Van de Mark had to see it for himself.

"They were being clear-cut logged, using the biggest tractors made," the photographer said. "The land was clearly being torn up pretty badly. ... I was deeply moved and angered by my first encounters of these practices soon after my arrival. Within a few months I bought a good camera and began taking pictures of everything I saw, including the destructive logging."

He had only been working at the mill for two days when Van de Mark asked where the trees being milled came from, and his co-workers hastily attempted to dampen his curiosity, to no avail. Van de Mark's hiking adventures quickly transformed from breezy, paved paths to trekking through difficult terrain in his efforts to bring awareness to redwood deforestation and timber company activity. He would journey through virgin forests and trudge across torn-up landscapes, often in the dead of winter, seeking humankind's first intrusions into old growth forests.

"Cold, wet and muddy," he recalled. "There was no more walking in state parks that had been saved, but now only on land you wanted to save. I was doing two simultaneous things: attempting to capture the beauty of the area and also the damage being done to it.

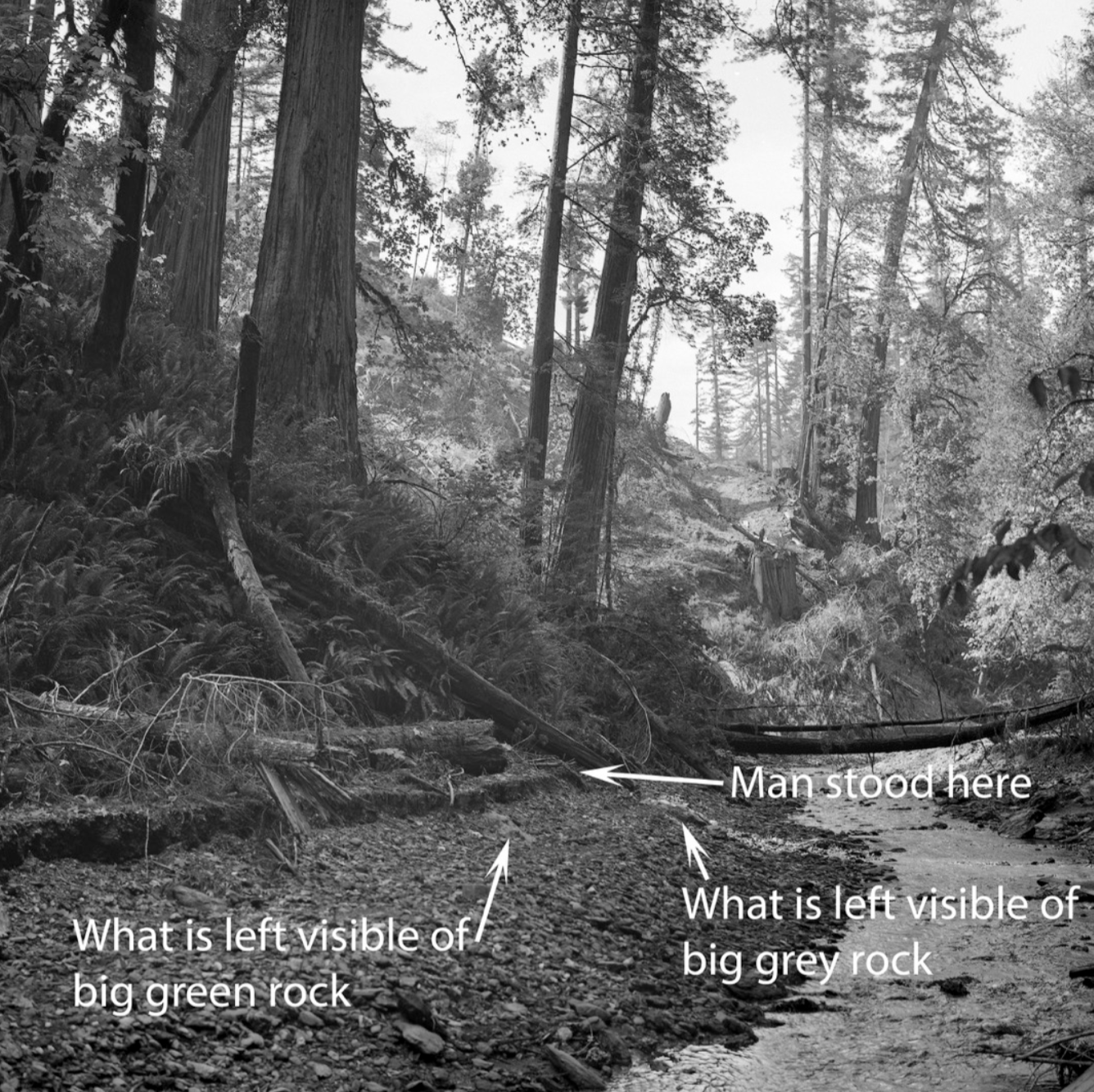

Emerald Mile upstream from Big Grove. Notice the boulder on the left: before the park's creation, Redwood Creek's channel was rising from upstream erosion. Riffles were shallow and the fine silt very easy to walk on. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

Today, the rock is ringed by deep water. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

"But, frequently there was precious little time to dwell on aesthetics, so it turned out a majority of my images concentrated on the destructive activities."

Boundless destruction

Just a year after his mission started, the backpacker-photographer saw how the deforesting behavior wounded the natural world firsthand. In 1964, Van de Mark experienced the infamous Christmas Flood, a surge of flooding that encompassed 200,000 square miles, claimed 47 lives and left thousands homeless as it decimated small communities throughout the northern half of California, nearly all of Oregon and portions of Idaho and Washington. The widespread clearcutting (complete razing of every tree in a given area, causing the destruction of an ecosystem and making the topography vulnerable to erosion and flooding) and roads built in association with the timber industry played a role in the catastrophic swell of water, mud and debris, Van de Mark explained.

"It didn't take waiting a year and a half for the results of this storm to profoundly affect me," he continued.

This photographer wasn't after damning exposés or gotcha moments, though—he was just a nature lover mourning a loss. "From flowers to mountains," Van de Mark was a wilderness backpacker with a penchant for documenting the world around him. Only after seeing the giants of the Golden State fall did Van de Mark realize his shutterbug hobby could be used as a serious tool in conservation activism.

In the meantime, some of the tallest redwood trees currently known to man had been discovered near Orick, California. The surrounding communities began discussion of forming a national park, which piqued the young backpacker's curiosity.

Van de Mark decided to get involved. He connected with area conservationists and continued to to look at the forest around him through a lens on each hike he took, accumulating more than 5,000 photographs of redwood destruction, about 80% of which were black and white. Van de Mark's photographic proof gained instant momentum, circulating worldwide. His work created a massive global awareness of the horrible conditions of these sacred old-growth forests that would soon vanish if nothing was done.

Most memorable to Van de mark is the ruin of Bridge Creek, a tributary to Redwood Creek a few miles upstream from the tallest trees in Orick. The creek "had a character about it that was unforgettable," he remembered. In autumn, maple branches clad in golden leaves hung over the creek surface against a background of fern-cloaked slopes. Sunlight fell in golden dapples through the branches. Peaceful and serene, the small side canyon was overseen by towering redwoods upward of 11 feet in diameter.

Van de Mark photographed the maple and redwood sanctuary long before the park was established; parts of Bridge Creek were unprotected, he said, and were heavily logged as a result. The clearcutting made the area vulnerable, and serious storming that followed devastated the area.

"The character of this place as I knew it was destroyed overnight by literally an over-your-head wall of mud of debris, which was repeated for many years," Van de Mark said.

A tall man stands by a tree on Bridge Creek on Oct. 14, 1966, before it was destroyed. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

The same section of Bridge Creek after the logging destroyed its beauty. Note the big gray and green colored rocks are buried in rubble. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

Bridge Creek has now begun a “recovery” 53 years later. Photo by Dave Van de Mark, Nov. 16, 2019

Though Bridge Creek has begun to heal, much log debris remains, which will take literally centuries to restore to the conditions seen in 1966 picture. Photo by Dave Van de Mark, 2019

Sprouting anew

Redwood National Park was established in 1968, five years after Van de Mark’s efforts began.

Van de Mark is known as a living legend in the areas surrounding the famous California redwoods. After the national park’s establishment, he donated the 5,000 images to the park. He also helped create and lead several organizations that ensured the establishment and expansion of several wilderness areas inland from the redwood coast.

After all the adventure—all the life-risking and the shutter-clicking—the conservationist is taking on one last task, in a delayed celebration of the park's 50th anniversary. The Fifty Years Later Project is an effort to photograph the extraordinary changes and stabilization now seen in the very places that were badly eroding five decades ago.

The view up the Geneva Road logging road along Lost Man Creek. October, 1964. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

The same view of Lost Man Creek Trail on March 17, 2019. Photo by Dave Van de Mark

"The 50th anniversary of Redwood National Park in 2018 sort of relit a fire under me, which led to my frequently revisiting the park and renewing my involvement with park staff," Van de Mark said. "My original proposal was founded in part on the unique circumstances that it’s possible for the same living photographer, who captured many one-of-a-kind images during the battle for the original park, and then its expansion, is available to return to some of those places for another look."

Originally slated to kick off in 2018 but delayed due to the pandemic, the Fifty Years Later Project will be pricey, and Van de Mark is seeking community support in funding the right camera, hiking gear and travel funds needed to safely complete his venture.

Using modern photographic equipment, Van de Mark will create a visual record of the landscape's restoration.

"What does the park look like now versus 50 years ago when thousands of acres of land was raw from recent logging? Pictures will tell!"

Van de Mark is just over $5,000 shy of his funding needs. Those interested in supporting Van de Mark's last ode to the redwoods can do so through his GoFundMe page.

To view Van de Mark's entire collection of Redwood National and State parks, visit davevandemarkphotography.smugmug.com.